Technology & Innovation

All Stories

Eric Siegel, Co-Founder & CEO, Gooder AI, argues machine learning (ML) projects go astray because their stakeholders focus too often on the technological fireworks — the “rocket science” of predictive models.

▸

9 min

—

with

We can’t edit tweets, but we can edit our own DNA.

▸

5 min

—

with

In the name of fighting horrific crimes, Apple threatens to open Pandora’s box.

Instead of digging for metals, we could extract them from salty, subterranean water.

The famous social robot is about to start rolling off the assembly line.

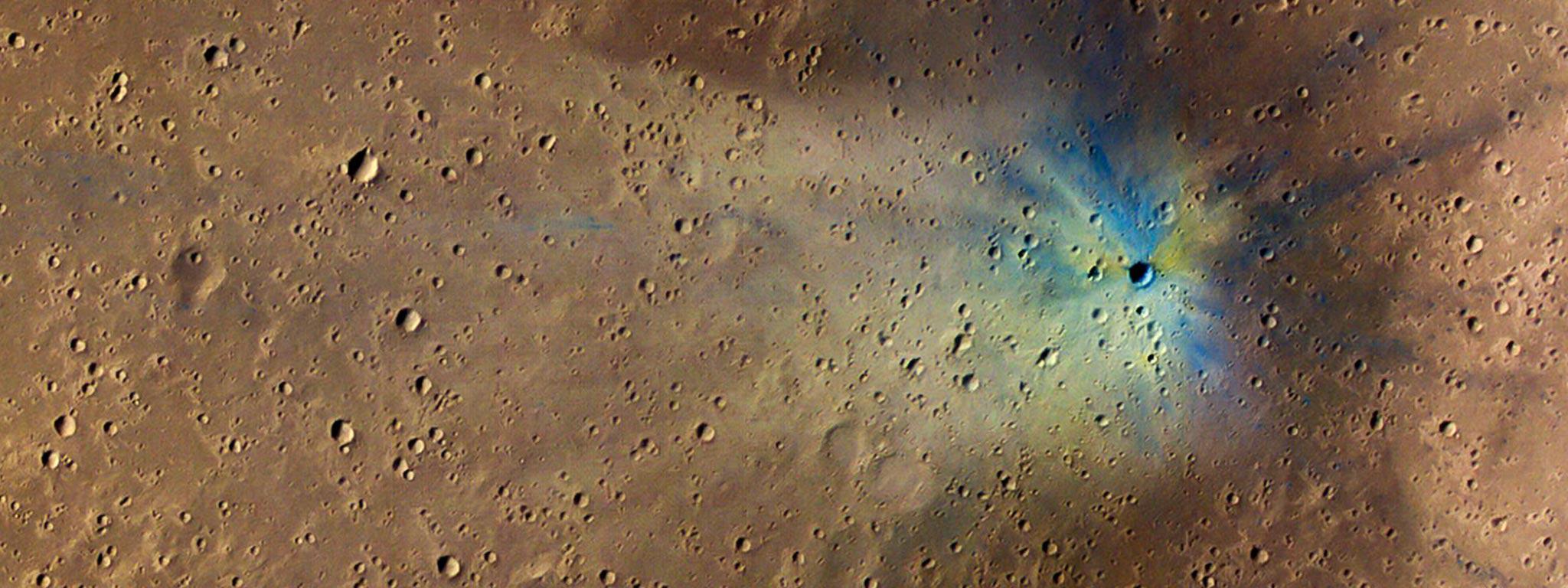

It could analyze a photo of the Martian surface in just five seconds. NASA scientists need 40 minutes.

Too many entrepreneurs care more about growing their audience at all costs than improving their ability to serve all sectors of their existing audience.

The world promised by the internet and social media is one where physical barriers are a thing of the past and communication is instantaneous. The current reality has some of […]

Recently, Tron appears to have been at the center of the latest fake news scandal to hit the crypto world. It started on July 8, after Twitter user Hayden Otto […]

35 hours a week would be ideal, say over 1,000 Americans surveyed. Just how overworked are we, really?

The Boring Company plans to build a new tunnel system that would connect residential garages to an underground hyperloop via elevator, potentially enabling people to someday enter the futuristic public transit system by simply stepping into their parked cars.

Apple unveiled the new Apple Watch Series 4 and three new iPhones during their keynote event on Wednesday, and they are chock-full of goodies.

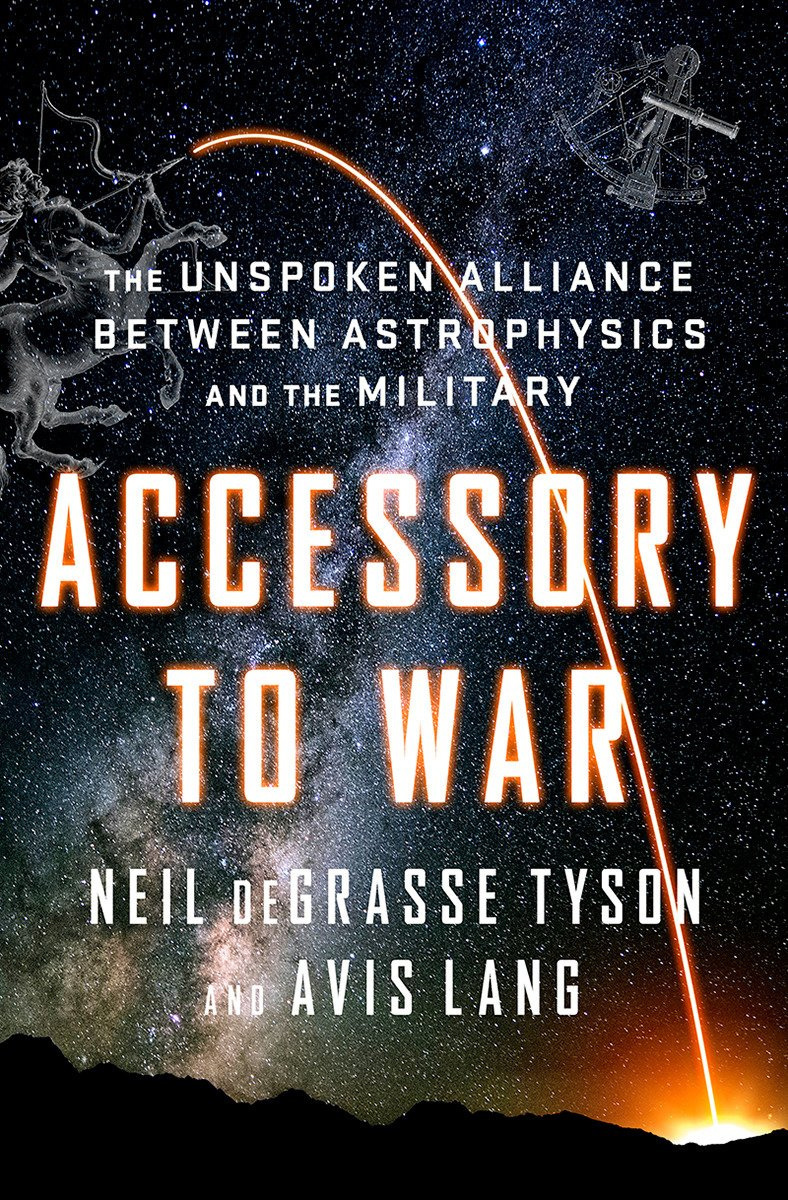

In a new book co-authored with Avis Lang, Neil deGrasse Tyson explores the morally complicated, symbiotic relationship between science and the military.

Istanbul’s “Smart Mobile Waste Transfer Centers” scan and assign a value to recyclables before crushing, shredding, and sorting the material. Will they help to prevent littering?

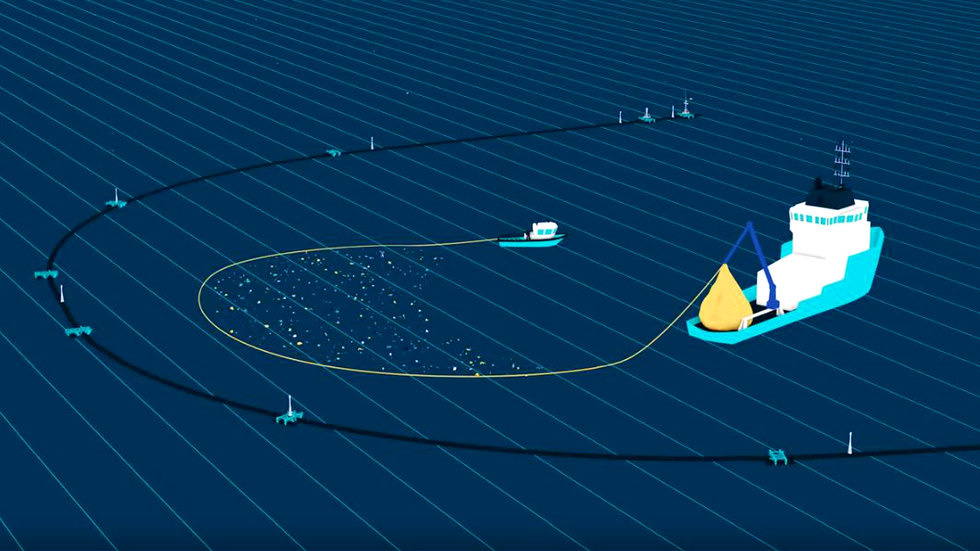

To raise awareness on one of the biggest environmental challenges of our time, the team partnered up with Adidas and Parley, a campaign group working to stop waste plastic getting into the oceans.

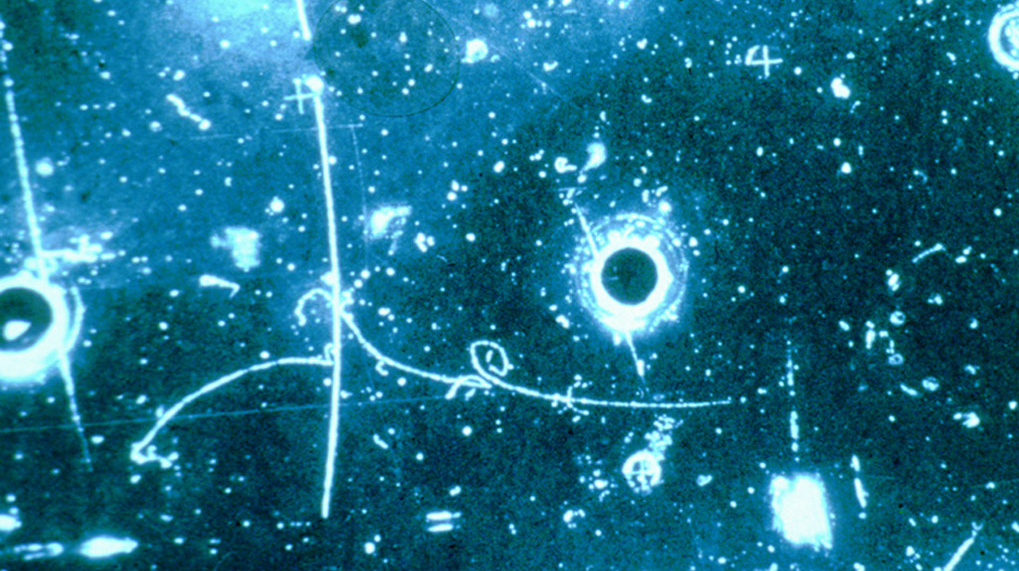

Quantum particles are mysterious and difficult to track down, but neutrinos may be the most elusive quantum particles yet. The facilities designed to observe neutrinos are feats of engineering, and what they hope to uncover is profound.

Among the hundreds and thousands of codes that have been broken by cryptographers, the government, and even self-taught amateurs tinkering around at home, there remain a small few of codes and devices which have yet to be cracked by anyone.

Love dogs? So does science.

Jaguar is trying to make pedestrians more comfortable around autonomous cars by giving vehicles cars human-like eyes that follow pedestrians to let them know the car ‘sees’ them.

As one of the biggest manmade structures in the sky and at a cost of over $100b, it’s the place where the space age dream is still alive.

Neural network learns speech patterns that predict depression in clinical interviews.

The biggest questions about cryptocurrency, answered.

The buildings of the future will be fluid, impermanent, and in constant transformation. But will human nature catch up?

Swirling in the Pacific Ocean is a loose patch of garbage that measures 1 million square miles—about three times the size of France. Now, one organization is beginning to clean it up.

The healthiest end-of-day sleep is 6 to 8 hours, but not more. Or less. As for napping, it depends on how you want to wake up.

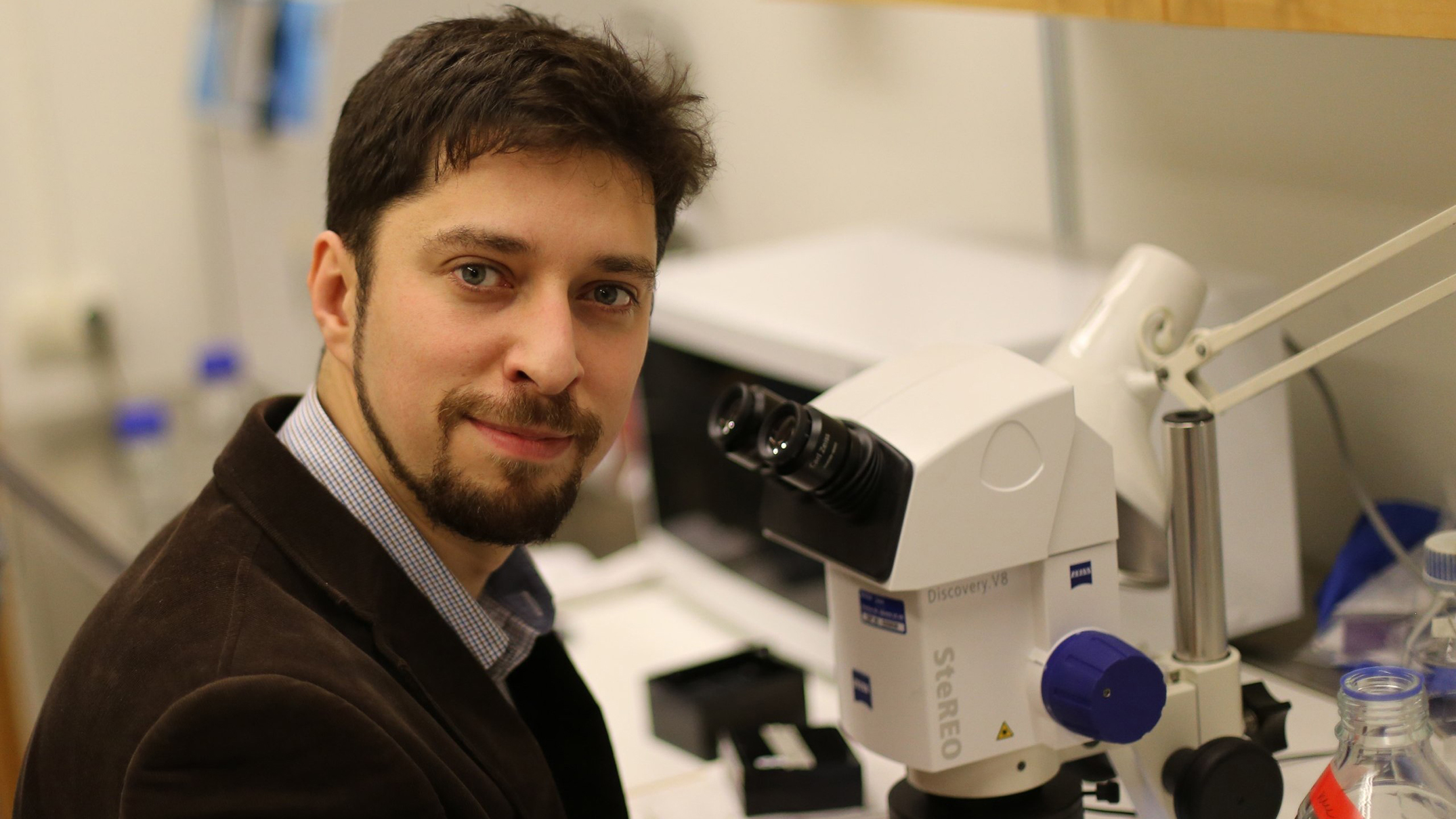

Could human beings one day regenerate limbs? It’s a distant possibility. But Adameyko Labs in Boston, Massachusetts is a good place to start thinking about it.

A recent op-ed in the New York Times says technology is not to blame for teens’ mental health struggles, but a new University of Michigan study suggests otherwise.

There are some big hurdles for Bitcoin to overcome. Cryptocurrencies must become practical for real-world use.

Recently released video and still images offer a rare view of uncontested indigenous residents of the Amazonian rainforest, including the solitary last member of his tribe.

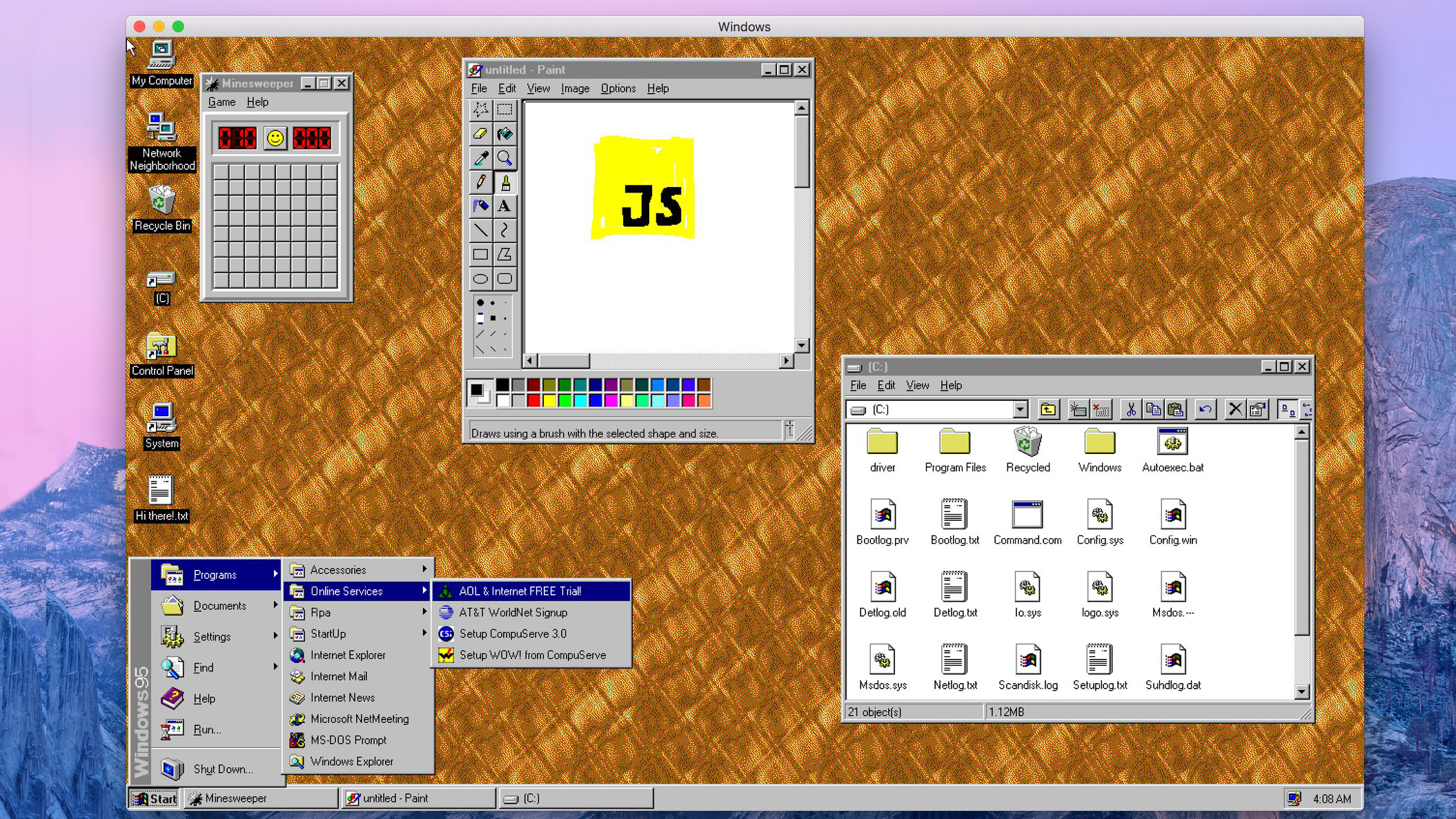

Microsoft Windows 95 was launched exactly 23 years ago today, selling for the tidy sum of $209.95. Now you can download it for free on almost any device. Go ahead. You know you want to.