A school district in Iowa is one of the first to outfit its administrators with body cameras. Their use should ease tensions with regard to transparency and accountability, but not everyone is happy with the precedent they set.

All Articles

“It is said that science fiction and fantasy are two different things. Science fiction is the improbable made possible, and fantasy is the impossible made probable.”

There are three things an idea must do to become a full-fledged scientific theory. How does the Multiverse stack up? “It’s hard to build models of inflation that don’t lead […]

Evolution can be seen as a process of discovering logic that works well in a particular environment. But evolution can’t see what our foresight can grasp. In some cases the logic inherent in relationships of need (e.g. within groups) can be decisive.

Researchers observe neurofeedback speeds, the likes of which a lab has never seen.

The Dutch city of Utrecht has set up an experiment to find out. Will everyone turn into lazy do-nothings or will people be encouraged to pursue passion projects?

In his dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges, the ruling that made same-sex marriage a constitutional right throughout the United States, Justice Clarence Thomas rejected the majority’s rationale that gays and […]

If you see a picture of a planet, can you identify which of the eight it is? “Don’t go around saying the world owes you a living. The world owes […]

Researchers predict the benefits of driverless taxis on the roads and the environment, and the outlook is good.

Researchers show how the pace of aging varies from person to person, and how chronological age is irrelevant when treating diseases—it’s biological age we should be concentrating on.

Philosophy professor and Buddhist scholar Evan Thompson discusses the concepts behind his latest book, Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation, and Philosophy.

If you want a vivid barometer for the health status of worldwide marine ecosystems, look no further than the global seabird population. Unfortunately, new research estimates that the global seabird population has dropped 70 percent since the 1950s. That’s not good.

That dizziness you reportedly feel after watching a 3D film may be all in your head.

The coming decade will see an emergence of new innovations that will keep drunk drivers off the road without the inconvenience of existing breathalyzer technology.

Researchers attempt to find out what triggers loneliness in the brain.

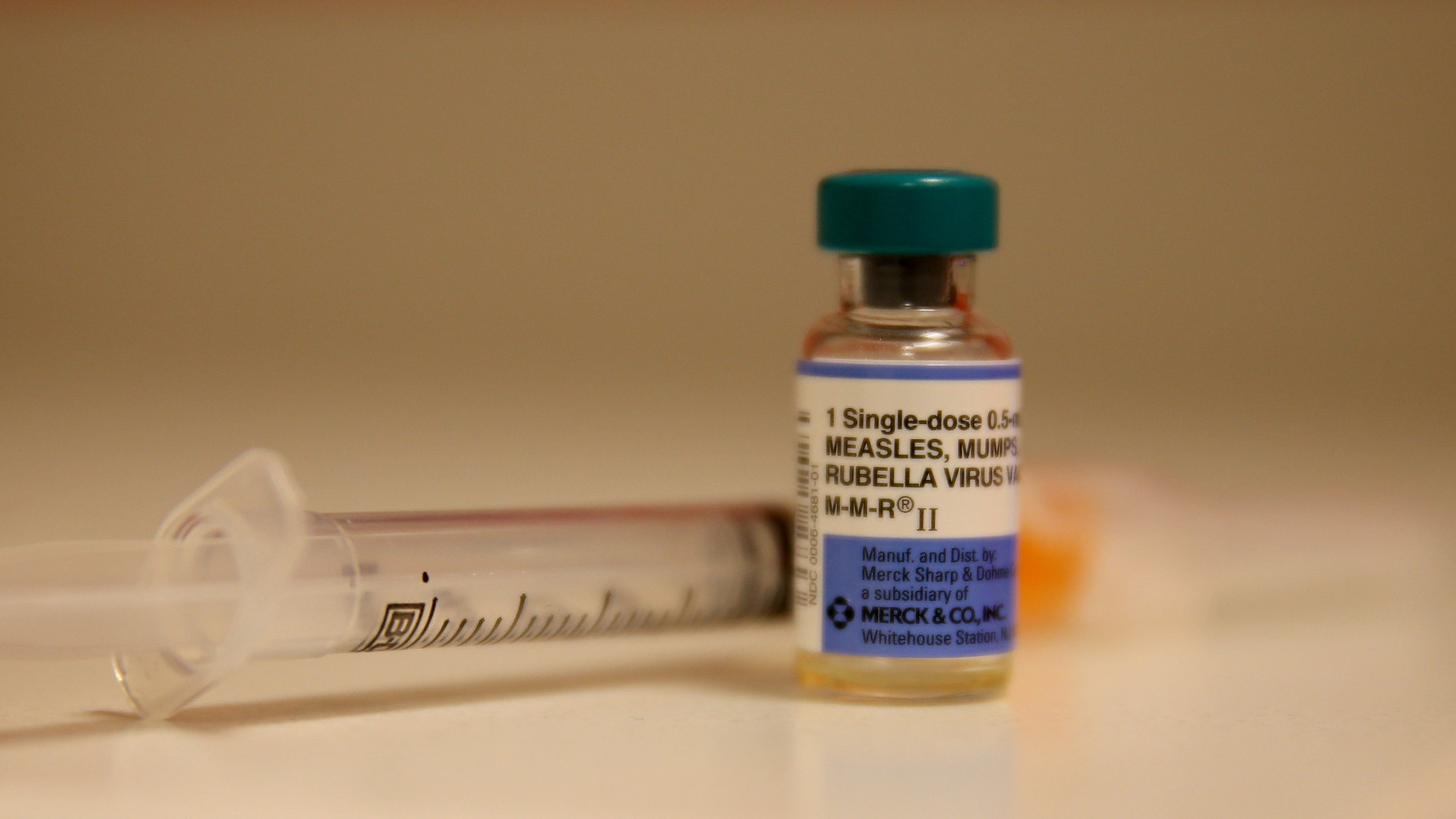

Researchers report recent outbreaks of preventable diseases have helped prove the benefits of vaccines and sway skeptical parents.

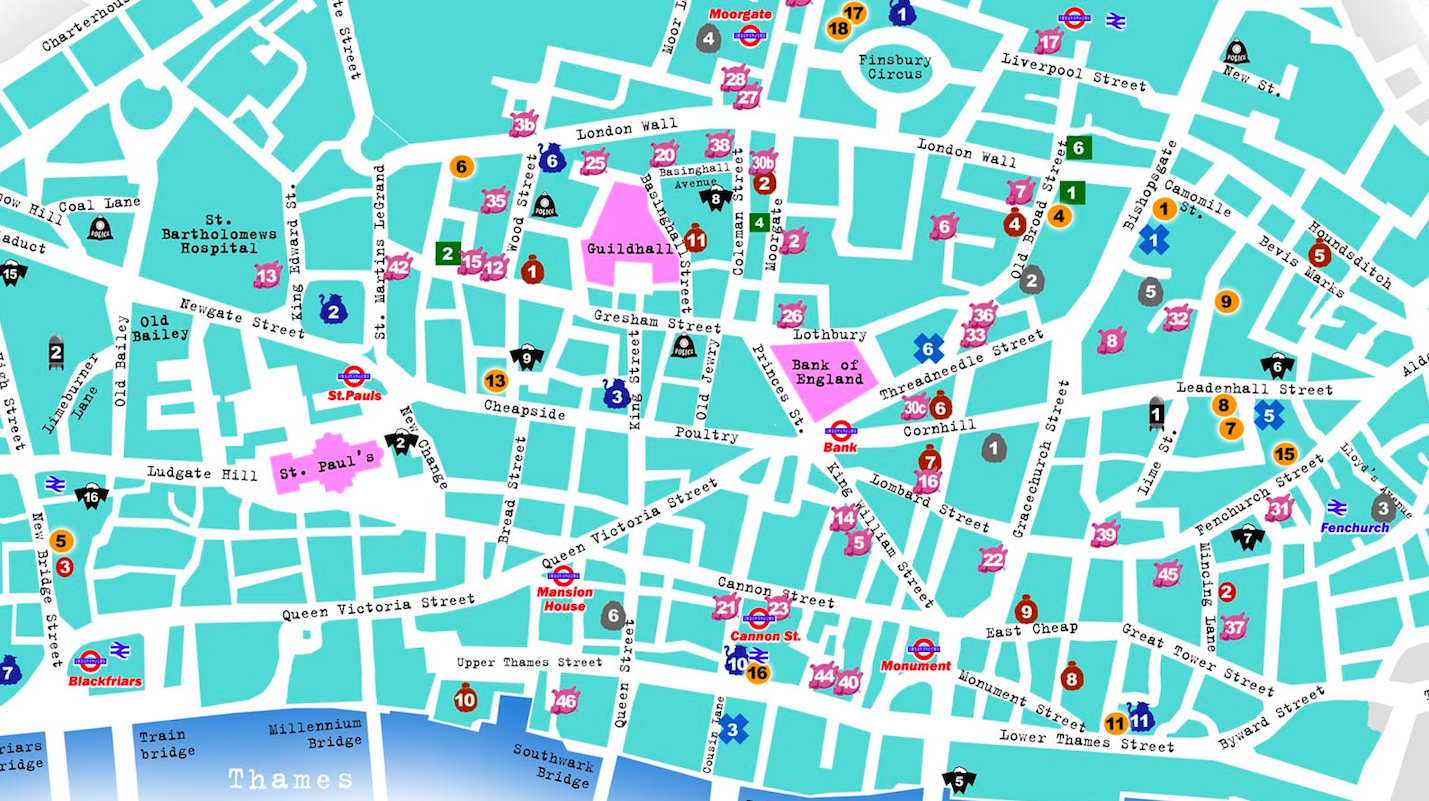

“Print this map. Get off the internet. Take to the streets.”

Researchers have found young women are less likely to use contraception.

Saw “Solar System Questions” by xkcd? Here’s what science thinks it knows. “Put two ships in the open sea, without wind or tide, and, at last, they will come together. […]

You’ll consume about 200 more calories than you would cooking a meal at home.

Study underlines the importance of relying on the right foods to get our sustenance — not pills.

A recent study makes a compelling new case for why we shouldn’t take drugs like Adderall precisely because they help us to succeed at things we otherwise wouldn’t.

Does the claim made by the leader of the €1 Billion Human Brain Project stand a chance of coming to fruition?

Dermatologists are taking advantage of smartphone technology to offer data-driven, personalized skincare recommendations.

Find out where the high points of your day are and save the busy work for when you hit your midday slump.

Emotional training may not stop repeat offenders, but it may help reduce the severity of their aggression.

The children of overbearing parents are less likely to develop essential life skills and are more likely to be medicated for depression or anxiety in college.

Because the technology is new, equipping a car with autonomous technology costs about $150,000 (the zero-emission fuel system comes standard).

Sensory Percussions reinvigorates music by giving drummers the ability to control electronic samples, synths, and audio effects with the artistry they have developed by playing their own acoustic drum kits.

Public apprehension about the health effects of mercury FAR exceeds the actual danger. Why, and what are the health impacts of that fear!?