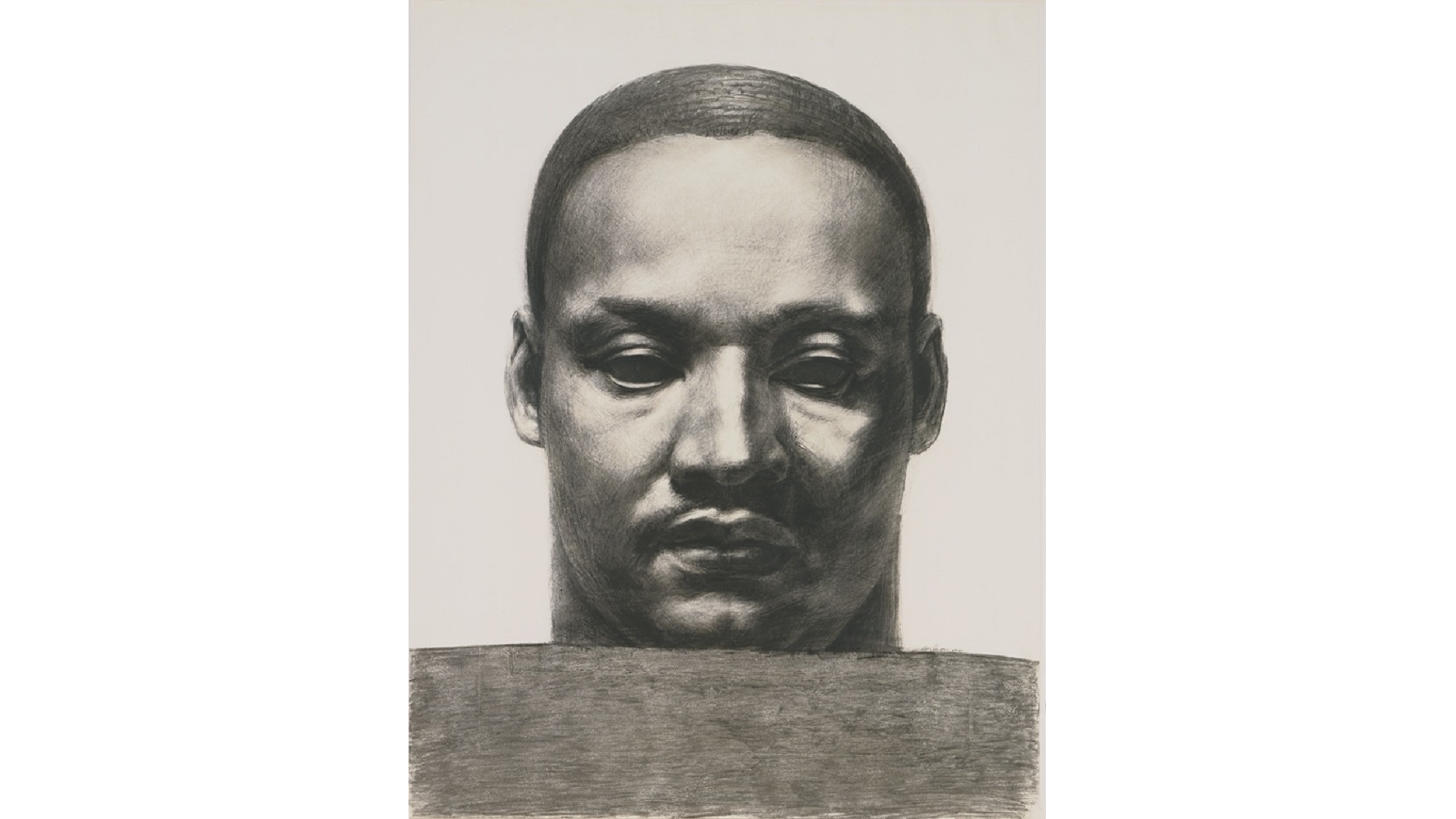

When the Philadelphia Museum of Art purchased Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting The Annunciation in 1899, they became the first American museum to acquire a work by an African-American artist. That purchase announced a new era of recognition of African-American art and artists just as much as the painting itself announced a new style of art moving away from stereotypical “black” scenes towards a freedom of aesthetic choice. Persons of color could express themselves in any way, even abstraction, but faced the new problem of remaining true to themselves at the same time. The new exhibition Represent: 200 Years of African American Art and accompanying catalogue show how these artists faced the challenges posed to them by art and society and provide all of us with a fascinating guide to facing African-American history—tragic, tenacious, transcendent—through its art.

All Articles

Spin a roulette wheel a million times, and you’ll see a fairly even split between black and red. But spin it a few dozen times, and there might be “streaks” of one or the other. The gambler’s fallacy leads bettors to believe that they odds are better if they bet against the streak. But the wheel has no memory of previous spins; for each round, leaving aside those pesky green zeroes, the odds for each color are always going to be 50-50.

When children believe that telling the truth will make their parents happy, they become less likely to lie.

Lack of exercise is more deadly than obesity, according to a study of 334,000 men and women which found that twice as many deaths are attributable to physical inactivity than to obesity.

Exercises that call for people to blindfold themselves in order to experience what it’s like to be blind may hurt perceptions of those who are disabled rather that help those with sight understand.

“I don’t think necessity is the mother of invention — invention, in my opinion, arises directly from idleness, possibly also from laziness. To save oneself trouble.”

How to figure out your location on Earth with only the most primitive tools. “And you may find yourself in another part of the world.And you may find yourself behind […]

A Dutch startup is working on behalf of seriously ill or dying patients to access experimental pharmaceutical drugs years before they are approved (or not) by governmental regulatory bodies.

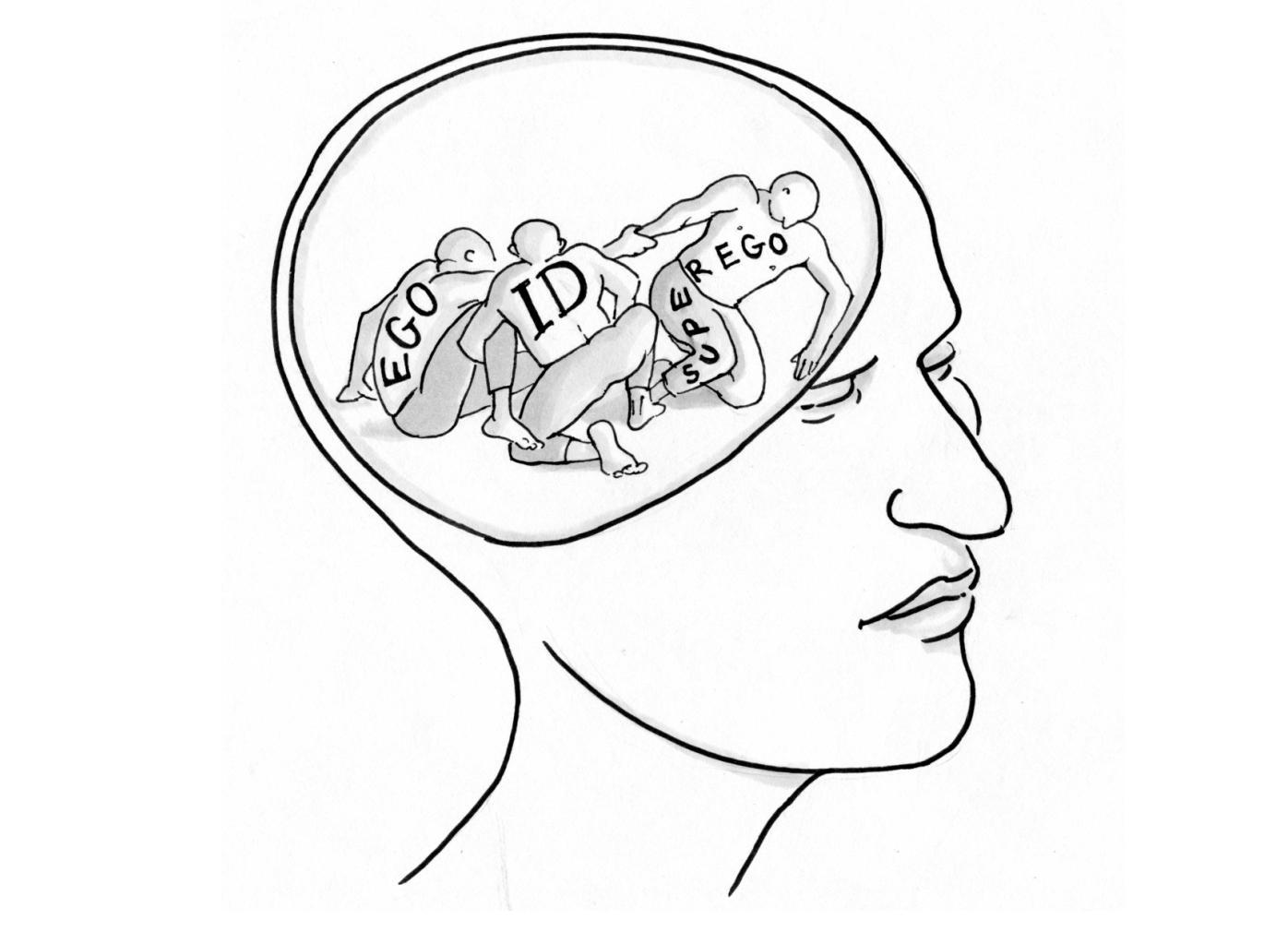

How our own minds work is hard to see. As with almost everything else our views are shaped by the ideas our culture uses. Here are some once-tempting views about why we do what we know we will rue (tales of sin, vice and bad decisions).

Either there’s an unseen source of mass, or the laws of gravity are wrong. But only one can explain what we see. “The discrepancy between what was expected and what […]

There’s a saying: Put a sweater on if your mother feels cold. It may seem silly, but a recent study shows that feeling cold can, indeed, be contagious.

The answer to that question is, probably not. Wherever people come together seeking goals – whether the same or different ones – and especially where there is competition for scarce resources, […]

Artists are being priced out of New York and other large urban centers. Some are moving to Detroit where houses go for a dollar; others are finding refuge in the suburbs.

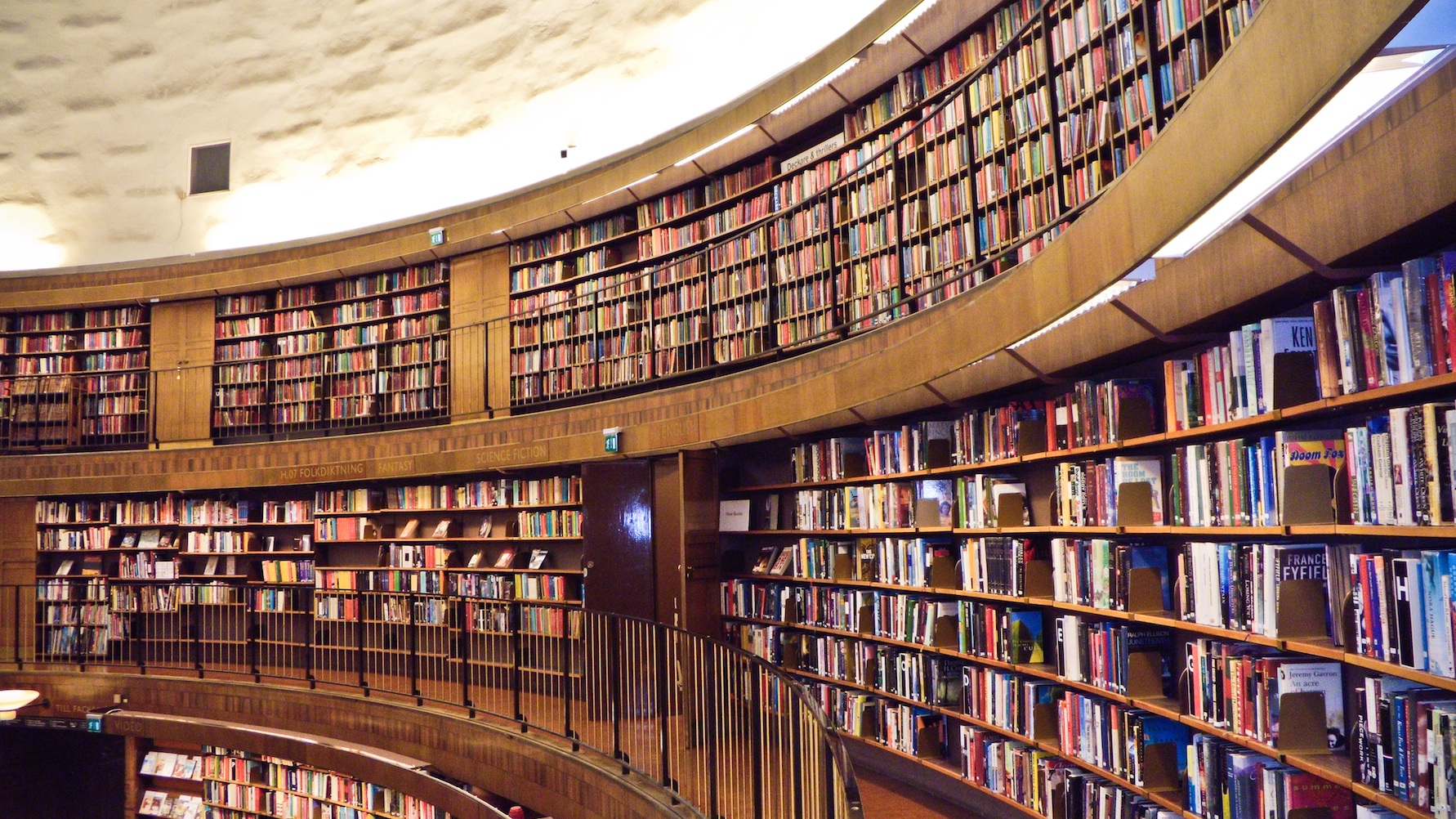

A new program out of Washington DC’s Public Library will attempt to answer some of the most important questions about personal privacy and security in America today, as well as show people how to use Tor.

The internet comments provide a means for researchers to asses people’s uninhibited, inner thoughts and feelings that they may not otherwise express if they weren’t anonymous. So, what do they have to say about women in STEM fields?

For decades now, an employment and wage gap has emerged between college graduates and individuals with only a high school diploma.

After a long day or week at the office it may feel appropriate to kick back with a beer. But a recent study has found workers who clock-in more and 48 hours in a week run the risk of developing a unhealthy alcohol habit.

In today’s featured discussion on pheromones, biologist Edward O. Wilson explains that there are massive amounts of natural stimuli that humans are not physically privy to.

“I am of the firm belief that everybody could write books and I never understand why they don’t. After all, everyone speaks. Once the grammar has been learnt it is simply talking on paper and in time learning what not to say.”

It may be prudent to save up just in case you run into a tough 6 months, but it’s also smart to start investing for the long term as soon as possible.

Different neighborhoods suit different personalities and when these metrics align, people are measurably happier.

Recent studies which look at the effects of kindness and generosity over time suggest that the cynical phrase “nice guys finish last” is false outside of isolated events.

Sleep plays a major role in our health. Adults who miss sleep tend to drag through the day, but for kids it plays a major role in their development and may have links to performance in math and language.

Encounters in the fourth dimension. We all have an intuitive sense of what a dimension is. There are only three perpendicular directions in which we might move, which we might […]

Taking notes by hand helps students learn more and it’s up to teachers to impose anti-screen policies in the classroom as a pedagogical tool.

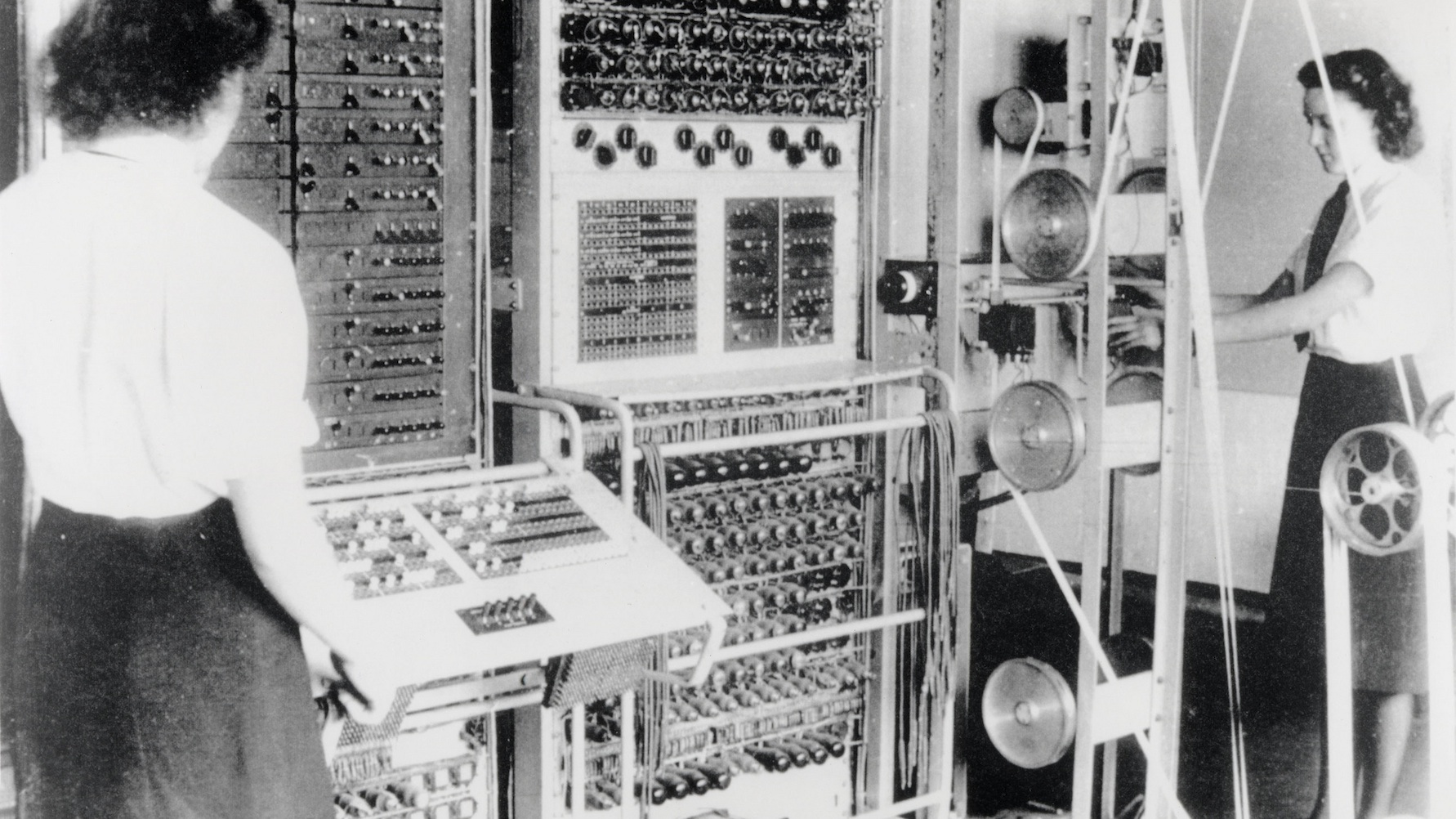

Up until the 1980s women made up a large part of the computing industry with 37 percent of women graduating with degrees in Computer Science. So, what happened to all the women? Advertising.

Unless you’re an astronomer, you’ve probably never heard of an analemma. And even if you are one, this might be your first tutulemma.

Fitness wearables do have the ability to facilitate change. But not if 42 percent of people stop using them after the first six months.

Smartphones hold so much of ourselves that if we didn’t have them, part of our minds would become inaccessible. So, what happens when you take someone’s smartphone away?

Burnout recovery is a four-phase process that starts with identifying that some goals are simply not attainable.