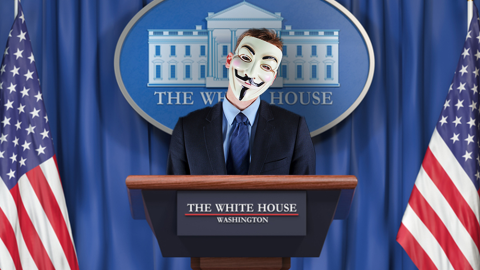

How governments are responding to the public’s demand for more data transparency

Depositphotos

- A study published last year by the Pew Research Center found that most American’s distrust the federal government, and there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that the situation has yet to improve.

- Governments have more access than ever to our private information, which creates an inherent tension between how they can use data for the public good while ensuring they aren’t abusing citizens’ privacy rights.

- As emerging technologies mature, it will become more evident to the public which models are the most effective ways for governments to achieve the levels of transparency they’ve committed to delivering.

Government transparency is a central tenet of liberal democracies. In many countries, including the United States, transparency is enshrined into the constitution and laws, such as the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act.

Nevertheless, trust in government is on the decline. A study published last year by the Pew Research Center found that most American’s distrust the federal government. Recent events such as the coronavirus pandemic, bailouts, and the Black Lives Matter protests casting a shadow over the Trump 2020 presidential campaign aren’t likely to have improved the situation.

However, it’s important to remember that this is hardly only an American problem. The Edelman Trust Barometer measures the trust in NGOs, business, government, and media. In 2020, the Barometer showed a drop in trust across many nations, including Canada, Australia, and the UK.

While governments risk decreasing public trust through their handling of events such as the pandemic, such events also create more pressure for governments to demonstrate transparency. The virus crisis results in inquiries into fields such as public health expenditure, while the protests are prompting calls to address institutional biases.

The increasingly prevalent use of technologies such as big data and AI means that governments have more access than ever to our private information. This creates an inherent tension between how governments can use data for the public good while ensuring they aren’t abusing citizens’ privacy rights.

European countries have recently been wrangling with this tension, as a privacy row has been brewing over the use of virus track-and-trace applications. An extremely effective way to curb infections happens to involve surveillance of the public with unprecedented precision and scale, and who’s to say what all the implications of allowing it may be? Who will gain access to this data, either legitimately or by hacking? What will they do with it? Once the pandemic ends, what happens to these access privileges?

Using emerging technologies inevitably increases the scope and scale of government data collection. However, technology can also be put to use by governments that want to demonstrate their commitment to improving transparency.

The Austrian government has recently turned to blockchain as a means of establishing transparent communications about the COVID-19 crisis, between authorities, institutions, and citizens. Communication specialist A-Trust has launched the QualiSig project, on Ignis, part of the Ardor blockchain platform.

The project will use transparent, encrypted communications visible on the blockchain, and decentralized data storage to secure data against attacks. Citizens can control the use of their own data using qualified digital signatures.

Alexander Pfeiffer, Danube University Krems researcher, and partner to A-Trust, has a high degree of confidence that blockchain can help to increase trust in governments. “The more such solutions are used by government agencies and their partners, the more likely it is that citizens will regain confidence in the operations of these government authorities,” he wrote in an email. “In addition, it will also be possible to work much more efficiently and on a much higher level of mutual trust between the parties involved.”

This is the second time the Austrian government has engaged Jelurida, the Swiss firm that operates Ardor, in projects designed to improve transparency. In May this year, the Austrian government announced funding for a sustainability project designed to pinpoint sources of waste heat that could be redirected back into the energy grid. The “Hot City” project is a collaboration with the Austrian Institute of Technology and plans to use the Ignis chain for providing rewards to citizens submitting data about waste heat that can be harnessed for the public good.

An outspoken advocate of using blockchain to increase transparency, Lior Yaffe is the co-founder and director of Jelurida. “For the Austrian government, funding applied blockchain technologies has been a major priority for several years,” he told Big Think. “Now, the Hot City and QualiSig projects show how a public blockchain can be used to store and display specific datasets, thus increasing transparency.”

The potential for using blockchain to demonstrate electoral transparency has been hotly discussed for years now. The first such experiment took place in Denmark back in 2014, when the Liberal Alliance party used blockchain for one of its local elections.

At the time, the chair of the party’s IT group made a bold prediction. “Voting is the most important process in a democratic society,” he said. “Here, there is no doubt that new technology will play an increasing role going forward.”

However, as things stand in 2020, blockchain in elections hasn’t moved forward at quite the pace many had previously predicted. Most local and national elections still take place using the same pen-and-paper process that has been in place for decades.

Nevertheless, the Indian election commission is among the latest to join the many government bodies that continue to experiment in this area.

Countries that have had problems with corruption going back generations have an especially steep mountain to climb when it comes to gaining public trust. Ukraine is one such example. As part of a bailout agreement in 2015, the International Monetary Fund demanded that the country’s government do more to fight corruption.

In 2017, the Ukrainian government engaged blockchain firm Bitfury to store all of its data on the blockchain, in an attempt to demonstrate better transparency. In September that year, the justice ministry successfully used the technology for auctioning seized assets, and later transferred state property and land registries to the platform.

“We want to make the system of selling seized assets more transparent and secure,” Deputy Justice Minister Serhiy Petukhov told Reuters, “so that the information there is accessible to everyone so that there aren’t concerns about possible manipulation.”

While technology can be a useful tool for governments to demonstrate transparency, it’s not the only means. Some countries, particularly those in northern Europe such as Norway and Denmark, are renowned for their culture of governmental transparency.

Canada also ranks highly in transparency from an international perspective, although its Corruption Perceptions Index score has been dropping.

It’s intriguing that domestic perceptions don’t always appear to align with these rankings. Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 crisis, some quarters of the Canadian academia have been highly critical of Justin Trudeau’s government.

“Canada has a culture of secrecy. And it’s one of the worst things about Canada,” Amir Attaran, professor of law and epidemiology at University of Ottawa, told the CBC. “Our lack of transparency is a Canadian cultural trait, and it’s one that hurts us. It’s also part of a larger belief that the government knows best. But it doesn’t.”

In the same piece, Jean-Noé Landry, who works for a non-profit that advises governments on data transparency, takes a more nuanced approach. He attributes a culture with a high level of government trust as a potential pitfall when it comes to demanding transparency in a crisis such as COVID-19. As he puts it, Canadians “trust the government more in these kinds of situations, and maybe we lower our guard a bit and go along with them. [COVID-19] is not the type of thing where we should be lowering our standards.”

One government that has been almost universally lauded for its handling of the coronavirus pandemic is New Zealand’s. Even before the crisis, the government there has been taking some impressive measures to demonstrate transparency. One example is its “algorithm assessment” program, launched in 2018, designed to introduce more transparency into how the government is deploying AI for its citizens.

Fourteen government agencies used a self-assessment method, underpinned by the government’s own “principles for safe and effective use of data and analytics.” The outcome was a report that acknowledged the need to retain human oversight over machine-led decisions and recommended using independent experts in the areas of privacy, ethics, and data expertise.

“We must prepare for the ethical challenges AI poses to our legal and political systems,” stated Clare Curran, New Zealand’s Minister for Digital Services, “as well as the impact AI will have on workforce planning, the wider issues of digital rights, data bias, transparency, and accountability are also important for this Government to consider.”

In the UK, the Open Data Institute (ODI) has been working on several pilots to implement “data trusts” in collaboration with various government agencies, in an attempt to create more transparency. The ODI defines a data trust as a “legal structure that provides independent stewardship of data.” They aim to increase access to data, along with providing confidence in the use of it.

The Institute worked on three pilots with varying degrees of success. The pilots attempted to bring transparency to food waste, illegal wildlife trade, and smart city implementation with a focus on parking data for green vehicles.

The findings from all three pilots were consolidated into a “lessons learned” document that highlighted the need to flesh out the overall concept and gain a shared understanding of what it means to all stakeholders for data trusts to become successful.

The ODI continues its work in this regard, exploring the use of data trusts and other data stewardship models.

The events of 2020 so far have amounted to a perfect storm as far as testing government trust goes. Social distancing and shelter in place rules mean that there’s a more significant reliance than ever on technology. However, governments need to continue to walk a tightrope of ensuring that they deploy the best technology available while demonstrating transparency.

As emerging technologies mature, it will become more evident to the public which models are the most effective ways for governments to achieve the levels of transparency they’ve committed to delivering.