The tragedy of Alexis de Tocqueville: The French aristocrat who spent his life trying to understand democracy

- At first glance, French statesman and philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville does not appear to have lived a particularly exciting life.

- However, closer inspection of his work reveals the quiet tragedy of a man who forsook his ancestry to defend his personal beliefs.

- Tocqueville was a revolutionary figure, but his methods were markedly different from other revolutionary figures.

Whenever a revolution seeks to overthrow a regime, the revolutionary leaders often grew up as part of the status quo. Vladimir Lenin, who claimed to be the voice of Russia’s working class, was actually a member of the intelligentsia. His father, Ilya Ulyanov, was not a peasant but a public administrator who studied math and physics at Kazan University.

Francisco Madero, the man who overthrew Porforio Díaz’s regime under the guise of granting greater autonomy to Mexican states and freeing laborers from their contracts to American robber barons, hailed from one of the country’s richest families. After becoming president himself, the once left-leaning Madero took up where Díaz left off, switching his allegiance from indigenous farmers and factory workers to their foreign employees.

Perhaps the best example of a changemaker who distanced themselves from their socioeconomic class is the French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville. Born to a wealthy aristocratic family, Tocqueville grew up in post-revolutionary Paris. As a youth, he heard stories of his missing family members: dukes and duchesses whose necks were placed under the guillotine by feverish mobs.

It was by way of these mobs that Tocqueville became acquainted with the concept of democracy — the same concept he would spend a lifetime studying. Like Lenin or Madero, Tocqueville leaned toward a cause that sought to dismantle the very source of his power. Unlike Lenin or Madero, Tocqueville pursued his cause more calmly and carefully, never falling prey to extremism or betraying those he claimed to want to help.

Compared to other historical figures, Tocqueville’s life and work seem to be anything except exciting. But if you read between the lines of his biographies — including an upcoming one written by social historian and University of Virginia professor Olivier Zunz — you will find a narrative that is every bit as moving as that of Maximilian Robespierre, Napoleon Bonaparte, or the Marquis de Lafayette.

Memories of revolutionary terror

Alexis de Tocqueville was born in Paris in 1805, a year after Napoleon Bonaparte crowned himself emperor of the French people. While Tocqueville’s parents managed to reclaim a considerable portion of their wealth and influence following the revolution, their family was by all means a share of its former self.

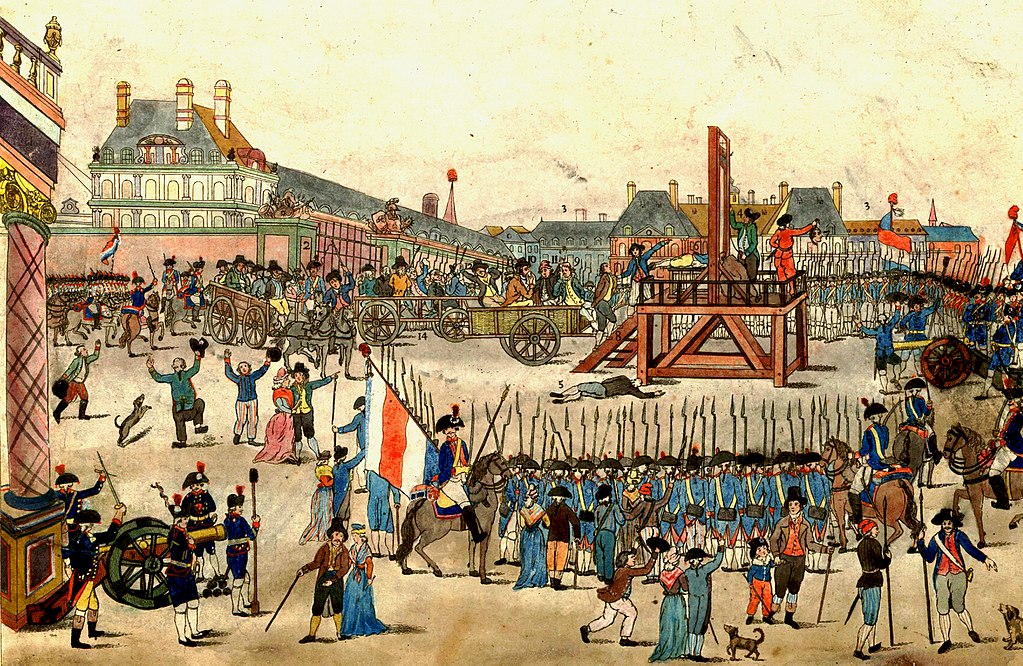

Tocqueville’s great-grandfather and patriarch, the statesmen Guillaume-Chrétien de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, was arrested during the Revolutionary Terror, as were ten other members of Tocqueville’s extended family. In spite of his progressive leanings, Malesherbes was beheaded by the same guillotine that, moments before his own death, had taken the lives of his daughter and several grandchildren.

All the while, Hervé and Louise-Madeleine — Tocqueville’s father and mother — were being jailed. They would have met the same fate as Malesherbes had his executioner, the lawyer Maximillian de Robespierre, not been executed himself at the end of Thermidor. The so-called Terror had consumed itself, and the revolutionary movement scattered.

The French Revolution made a powerful impression on Tocqueville’s parents. The already conservative Hervé, who eventually became a successful government administrator, was transformed into a single-minded royalist suspicious of any and all forms of dissent. He played a small but important role during the Bourbon Restoration, which sought to reinstate France’s monarchy after the fall of Bonaparte.

Louis-Madeleine, who had been susceptible to melancholy since she was a child, fell into a depression she would never again escape. Aside from losing multiple loved ones, she had spent the first ten months of her marriage in a jail cell, awaiting the announcement of her own death. Her spirits were lifted only by the birth of her son Alexis, who Hervé described in his memoirs as destined to become “a man of distinction.”

Tocqueville’s Democracy in America

France’s first encounter with democracy left the country’s surviving elite even wearier of social change than they had been before. But while Hervé and his wife associated progressive politics with the uncontrollable mobs that attempted to murder them, their son quickly came to the realization that democratic revolution need not always lead to revolutionary terror.

Tocqueville’s personal beliefs, acquired through a mix of observation and independent research, inevitably caused a rift between his family — one that, though it remained largely unspoken, was nonetheless ever-present. As Zunz surmises in his forthcoming biography, The Man who Understood Democracy, “It was in mourning not for his family but for the recent demise of democracy in France” that Tocqueville would go on to dedicate his most insightful texts.

The first and arguably most important of these texts, Democracy in America, was conceived in 1831. That year, Tocqueville — then a government official — was sent on an expedition to study the design, conditions, and effectiveness of the U.S. prison system. During his travels across Jacksonian America, Tocqueville observed not just the republic’s prisons and penitentiaries, but also its culture, economy, and politics.

Here, Tocqueville encountered another, more positive outcome of revolutionary strive. At the time, America was the only country in the Western world where democratic revolution had not backfired on itself, but rather succeeded in building a new type of society. Among other things, Tocqueville hoped that the sociological study of American society would help him better understand the prerequisites of establishing a sustainable democracy.

“It is indeed difficult to imagine,” reads one of many observations in Democracy in America, “how men who have entirely renounced the habit of managing their own affairs could be successful in choosing those who ought to lead them. It is impossible to believe that a liberal, energetic, and wise government can ever emerge from the ballots of a nation of servants.”

Return to France

The fact that the U.S. succeeded where Europe failed may have something to do with the fact that American society was, in the eyes of its architects, an opportunity to start over from scratch and rebuild the machinery of government without installing the parts which European history had demonstrated to be broken or dysfunctional.

When Tocqueville returned to France and entered politics to apply what he had learned in America, he did not enjoy the same luxury as the Founding Fathers had. During this time, France had seen more revolutions and counter-revolutions than its citizens were able to keep track of. Society had splintered into different movements, all of which proposed irreconcilable demands.

Assuming the role of a politician rather than a revolutionary, Tocqueville’s influence over government affairs was limited, though often decisive. When the Revolution of 1848 led France’s last monarch to abdicate, Tocqueville joined a group appointed to draft the country’s next constitution. During discussions, Tocqueville advocated bicameralism, the advantages of which he had witnessed across the Atlantic.

Both before, during, and after the Revolution of 1848, Tocqueville campaigned for the restriction of civil liberties, notably freedom of press and association. Some have seen this as contradictory to the beliefs outlined in Democracy in America, but this is not necessarily the case. As Joseph Epstein explains in Alexis De Tocqueville: Democracy’s Guide, Tocqueville saw order as the “sine qua non for the conduct of serious politics.”

Epstein suggests Tocqueville wanted to “bring the kind of stability to French political life that would permit the steady growth of liberty unimpeded by the regular rumblings of the earthquakes of revolutionary change.” A more dramatic interpretation holds that Tocqueville, weary of revolutionary zealotry, planned to pacify the masses before they lost control of themselves.

The legacy of Alexis de Tocqueville

“Great thinkers,” Zunz writes in the prologue of his biography, “do not always have a life worthy of detailed telling. We often understand them better in conversation with other great minds across the ages rather than with their contemporaries.” But, in this respect, “Alexis de Tocqueville stands apart.”

Where another great thinker, Immanuel Kant, composed the majority of his philosophic oeuvre without ever setting foot off his estate near Königsberg, Tocqueville preferred to see things for himself before he wrote about them. By the end of his life he had become, according to both current and contemporary standards, a certified globetrotter.

More astonishing than these travels themselves are the symbolic significance they held for Tocqueville. It was already mentioned how, at the start of his life, Tocqueville pursued beliefs that ostracized him from his family. Trusting his own morality and reason, he continued to defend these beliefs even as many real-world developments suggested he was wrong.

At the end of his career in politics, Tocqueville found himself siding with the Bourbons because he thought their reign, if mediated by the right constitution, was a more effective path toward democratic reform. He threw his hat in the ring when the rest of France cast their votes in favor of what had since become another family of power-hungry aristocrats: the Bonapartes.

Throughout Tocqueville’s life, the success and stability of America had been his greatest consolation, a possible confirmation that his obsession with democracy was not misguided. In a final stroke of tragedy, however, Tocqueville succumbed to tuberculosis just two years before the start of the American Civil War, a time in which the world would hold its breath waiting to see whether or not democracy was done for.