Rare fossil depicting battle sheds light on ancient ant

Barden et al., Current Biology, 2020

- A fossil of a prehistoric ant hunting has recently been discovered.

- Fossilization is rare, so depictions of activities like hunting are hard to come by.

- Other fossils show us how dinosaurs hunted, fought, and died.

Any animal with the name “hell ant” is going to be freaky. Now, thanks to a one-in-a-million chance find, we know how exactly how strange the hell ant was.

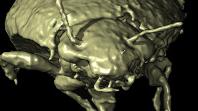

The infernally named insect has been extinct since the cretaceous period and has long puzzled paleontologists with its curiously shaped mandibles. Now, thanks to the discovery of a hunk of amber containing both a hell ant, or Ceratomyrmex ellenbergeri for the Latin inclined, eating an ancient cockroach.

Unlike nearly all currently existing insects, the hell ant has mandibles that open up and down rather than left and right. While scientists had speculated that this strange bug used its lower mandible to clamp prey to the horn-like upper mandible, it is only with this fossil’s discovery that we can know that for sure. According to Science Alert, this is the first time we’ve found a fossil of this demon ant eating.

Assistant Professor Phillip Barden of the New Jersey Institute of Technology, who authored the study on the fossil, expanded on the significance of the find in Eureka Alert:

“Fossilized behavior is exceedingly rare, predation especially so. As paleontologists, we speculate about the function of ancient adaptations using available evidence, but to see an extinct predator caught in the act of capturing its prey is invaluable. This fossilized predation confirms our hypothesis for how hell ant mouthparts worked … The only way for prey to be captured in such an arrangement is for the ant mouthparts to move up and downward in a direction unlike that of all living ants and nearly all insects.”

Fossilization of any kind is infrequent. While the things that must go right for it to happen vary on the method, a typical dinosaur fossil would have to be buried in minerals conducive to fossilization before too much of it decays or is scattered away.

The odds of this happening are low. The odds of this happening with two animals that were fighting at the time of their death are even lower. However, improbability is not the same as impossibility, and several other fantastic examples of ancient predators engaged in life and death struggles with their prey have been preserved.

By Yuya Tamai from Gifu, Japan – 2014-03-25 13.04.52, CC BY 2.0

One of the more famous fossils of all time is a depiction of a velociraptor fighting a protoceratops. In the above picture, you can see the raptor’s slashing claw where the neck of the protoceratops once was and the raptor’s forearm caught in the beak of its prey.

Discovered by a Polish-Mongolian team in the seventies, these remains are thought to have been preserved by the rapid collapse of a sand dune onto the battling animals, or by their rapid burial in a sandstorm.

Not only is this fantastic to look at, but it provides us with evidence about how these species of dinosaur behaved that more typical remains cannot offer. For example, while it was commonly supposed that a velociraptor’s claw was used to disembowel prey, this scene demonstrates that it was likely used elsewhere. Some have even gone so far as to suggest it wasn’t designed to create slashing wounds at all, but instead was used to grab prey.

Two fossilized dinosaur skeletons dubbed the ‘Montana Dueling Dinosaurs’ will be auctioned in New Yowww.youtube.com

The subject of an extended ownership debate that was only recently settled, this fossil has yet to be seen by the public and has already been built into the stuff of legend.

It depicts a Tyrannosaurs-esque predator locked in combat with a potentially unknown member of the ceratopidae family (that’s the group that has horns on their faces, like the eternally loved triceratops). The extended court cases around the ownership of the remains haven’t been able to eclipse the find’s incredible nature.

In addition to depicting predation, the Tyrannosaurus fossil is nearly complete, making it one of about a dozen near-complete T-Rex fossils.

Clayton Phipps, the discoverer of the fossils, further explained how incredible the find was to Smithsonian Magazine: “There’s an entire skin envelope around both dinosaurs,” Phipps says. “They’re basically mummies. There could be soft tissue inside.”

Others are less convinced of the importance of this discovery. John Horner, the paleontologist who dug up the famous T-Rex known as “Sue,” dismissed the find as “scientifically useless” due to the lack of data collected at the site by the people who dug it up.

Despite his objections, interest in the fossil remains high, likely due to the aforementioned rarity of such a depiction by a fossil.