virus

A new study looks at what happens when you get infected with two viruses at the same time.

A team of scientists managed to install onto a smartphone a spectrometer that’s capable of identifying specific molecules — with cheap parts you can buy online.

People may be more willing to get vaccinated when told how popular it is.

A psychologist and a doctor of emergency medicine explain.

The vaccine will shorten the “shedding” time.

Beyond making up 70% of the world’s health workers, women researchers have been at the cutting edge of coronavirus research.

Researchers analyze prehistoric viruses in animals dug out from the Siberian permafrost.

Pandemics have historically given way to social revolution. What will the post-COVID revolution be?

Northwell Health has built an elaborate data system to track and fight COVID-19. If this system goes global, it could prevent a future pandemic.

▸

3 min

—

with

The long-term lessons America learns from the coronavirus pandemic will spell life or death.

▸

3 min

—

with

Ultraviolet LED lights could soon be used to help disinfect air and surfaces in buildings, planes, subways and other spaces.

The researchers trained the model on tens of thousands of samples of coughs, as well as spoken words.

Instead of looking forward, we should be consulting the past.

Northwell Health CEO Michael Dowling has an important favor to ask of the American people.

▸

1 min

—

with

The images were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and show how prolific coronavirus can become in a mere four days.

Some people choose alternatives to masks for comfort. A study shows the difference in effectiveness.

Various studies examine the impact of humidity, temperature, rain, and sunshine on COVID-19.

The patient’s second infection was asymptomatic, suggesting that subsequent infections may be milder.

DNA molecules are highly programmable.

Despite unregulated face coverings being highly variable, they do, on average, reduce the spread of the virus.

Innovative drugs are sometimes held up due to old-fashioned human biases.

The larger the stakes and scope, the less likely a conspiracy theory is to be true.

▸

4 min

—

with

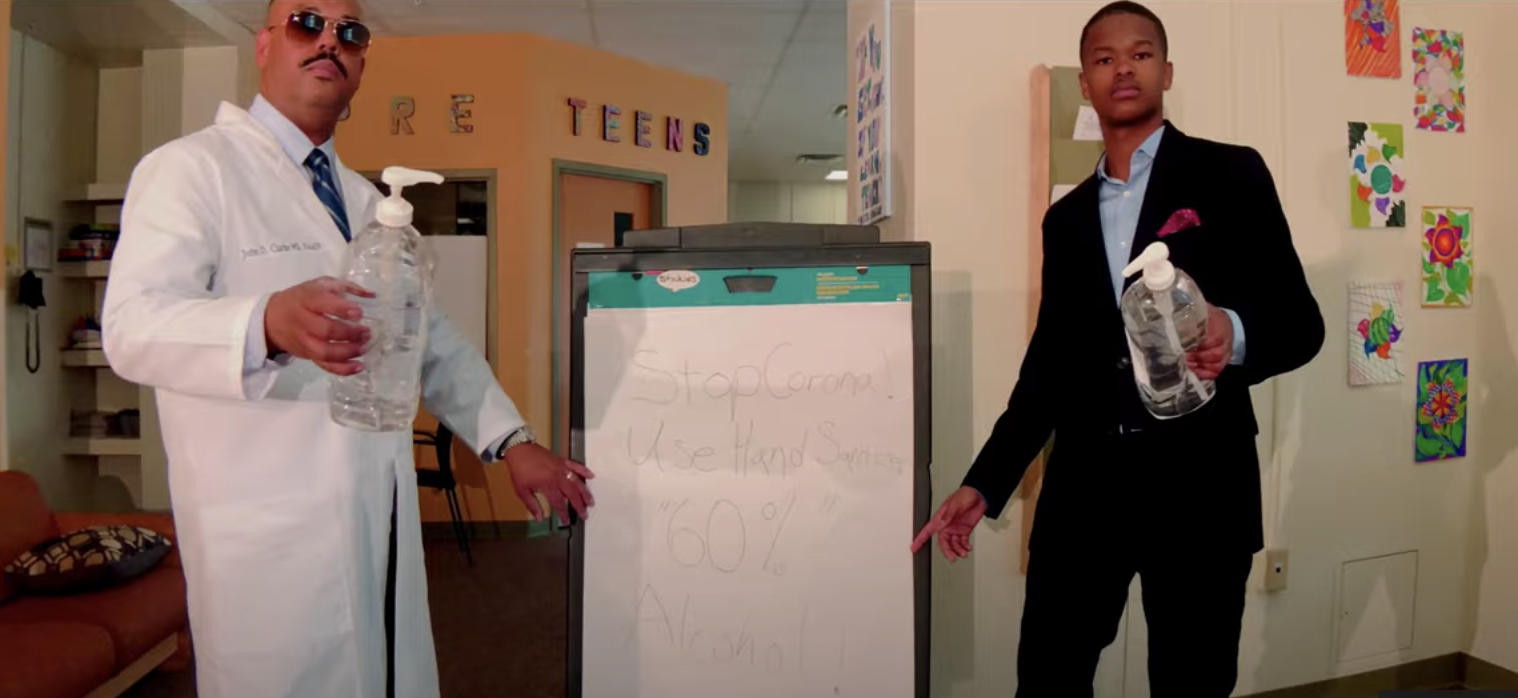

A Cornell Health physician has blended rap and medicine to better educate kids on coronavirus guidelines.

The physical action of handwashing plus the properties of soap is a one-two punch for the virus.

▸

1 min

—

with

Apps that warn about close contact with COVID-19 cases can help relax social distancing rules.

Combining two fabrics is the best way to filter out infectious coronavirus particles according to a new study.

An antibody produced by llamas seems particularly effective at neutralizing a key protein of the novel coronavirus.

Dr. Kate Biberdorf explains why boiling water makes it safer and how water molecules are unusual and cool.

▸

3 min

—

with

Men take longer to clear COVID-19 from their systems; a male-only coronavirus repository may be why.