self

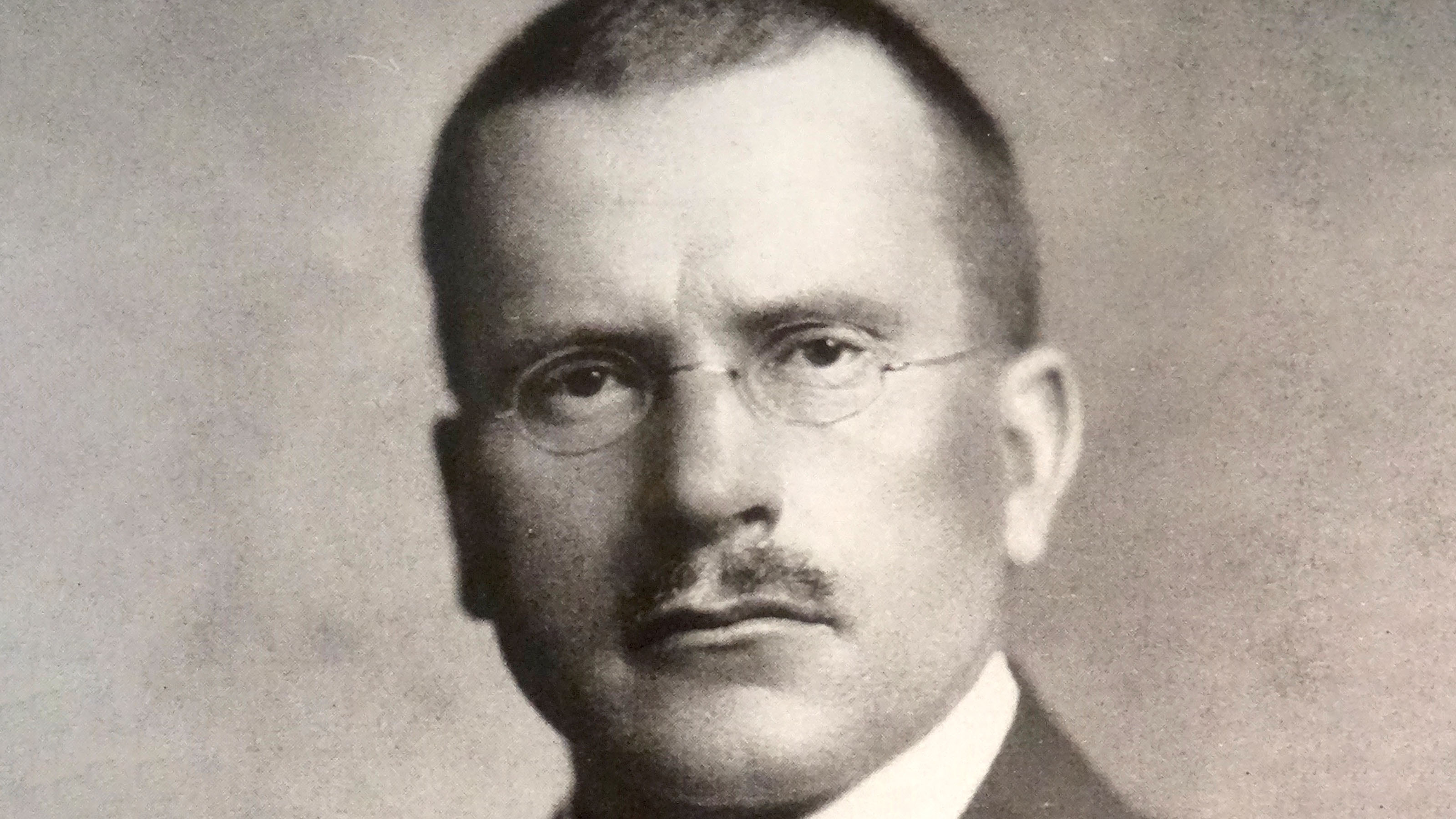

Carl Jung was one such person.

Balancing realism and optimism in a dire situation is a key to success.

The number of PhDs has been exceeding the available academic positions since as early as the mid-1990s.

Companies can identify you from your music preferences, as well as influence and profit from your behavior.

Philosophers, theoretical physicists, psychologists, and others consider what or who is really in control.

▸

19 min

—

with

In-depth research suggests BDSM practitioners can experience altered states of consciousness that can be therapeutic.

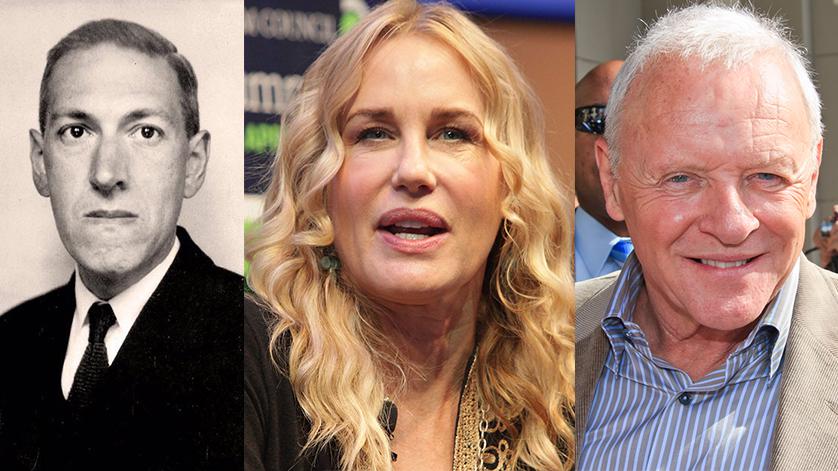

Words of wisdom from H.P. Lovecraft, Sir Anthony Hopkins, Dr. Temple Grandin, Hannah Gadsby and more.

What can ‘behaviorism’ teach us about ourselves?

Life is absurd, that detail can be the start of a great many things.

New research identifies 16 different COVID-19 personality types and the lessons we can learn from this global pandemic.

Lovers are parted from lovers, (grand)parents from children, families from their dead.

Answering the question of who you are is not an easy task. Let’s unpack what culture, philosophy, and neuroscience have to say.

▸

12 min

—

with

Psychologists point to specific reasons that make it hard for us to admit our wrongdoing.

A popular and longstanding wave of thought in psychology and psychotherapy is that diagnosis is not relevant for practitioners in those fields.

The Persian polymath and philosopher of the Islamic Golden Age teaches us about self-awareness.

Learn how to practice “self-indifference.”

No, being interested in BDSM does not mean you had a traumatic childhood.

Habits are easier to hack and change when you understand how they work.

▸

12 min

—

with

As morally sturdy as we may feel, it turns out that humans are natural hypocrites when it comes to passing moral judgment.

▸

5 min

—

with

Research finds that our sense of self can be manipulated by certain smells and sounds.

Fractal patterns are noticed by people of all ages, even small children, and have significant calming effects.

Is the quest to upload human consciousness and ditch our meat puppets the future—or is it fool’s gold?

▸

14 min

—

with

There is a lot we don’t know about psychedelics, but what we do know makes them extremely important.

▸

20 min

—

with

Neuroscientists and ethicists wants to ensure that neurotechnologies remain benevolent.

A new study found that personality growth in young adults predicted career benefits such as income, degree attainment, and job satisfaction.

Philosophers have been asking the question for hundreds of years. Now neuroscientists are joining the quest to find out.

▸

6 min

—

with

What is human dignity? Here’s a primer, told through 200 years of great essays, lectures, and novels.

Is your masturbation routine benefitting your sex life? Here’s how to tell…