What should jail sentences for drug crimes be? This survey asked Americans

While it’s true that Pew Research Center, working with data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, has recently reported that 2016 reached a 20-year low in the number of people incarcerated in the U.S., it’s nonetheless still the case that no other country jails as many of its residents. In 2016, there were about 2.2 million Americans doing time, about 1.5 million in federal custody and another 741,000 in local jails.

Many of these inmates are being held for non-violent drug crimes, with sentences formulated during an era when experts believed harsher consequences would lower drug use. This hasn’t happened, and it’s recognized these days by most Americans that the sentencing system is plagued by unfairness and bias, and that it pointlessly destroys lives and communities.

As a result, in 2013, the Obama administration released new guidance that awarded judges more leeway to reduce sentences for non-violent defendants. The Trump administration apparently disagrees, with Attorney General Jeff Sessions rolling back that guidance in order to encourage the dispensation of the harshest penalties possible. Sessions’ action is out of step with American opinion and the data on recidivism, as are the many antiquated laws still on the books.

Addiction Now recently polled 1,000 Americans to learn what they thought appropriate types of punishments and their optimal durations would be. Juxtaposing those opinions against the actual sentences in a series of infographics does nothing to dispel the image of a nation with too many prisons and prisoners.

All infographics by Addiction Now.

Is there discrimination in sentencing?

The first most obvious problem with our judicial system is the uneven way it’s applied to those outside the white upper-middle classes. Addiction Now asked respondents about the degree of racial discrimination they see in sentencing and sorted their answers by their race and their political party affiliation: Democrat, Independent, Libertarian, and Republican. Next, they asked about socio-economic bias, again sorting the response racially and then by party.

Clear majorities of most groups recognized both types of bias with the exception of Republicans, only 47% of whom agreed that sentencing is racially biased.

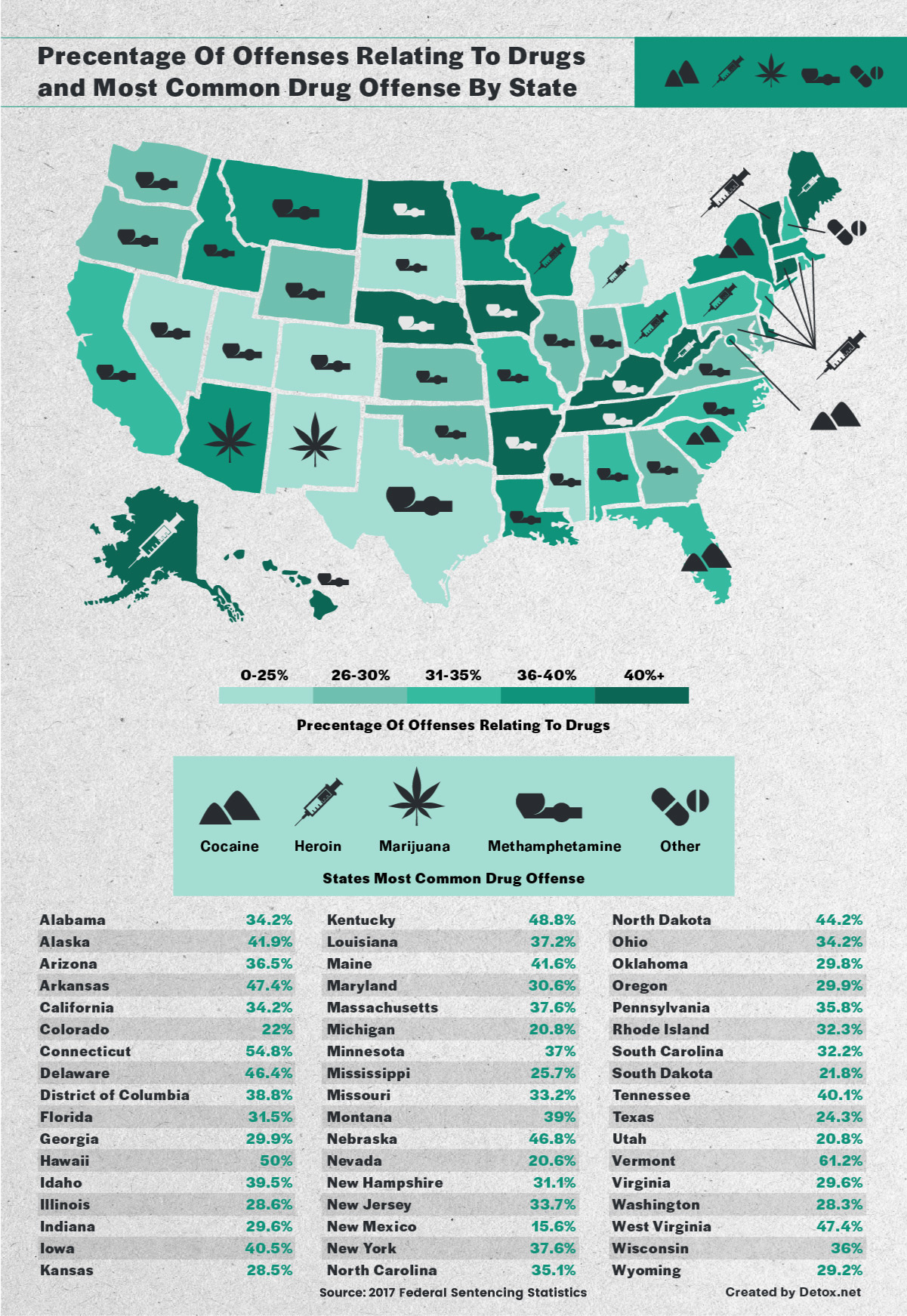

Pot

The biggest disconnect—no surprise—is with marijuana. While recreational smoking is now legal in 29 states, and 64% of Americans support legalization, the drug sentences being handed out, even for simple possession, are still draconian. With the chart’s 60% of Americans believing there should be no sentence for grass possession—and another 25% suggesting probation only—a whopping 89% of U.S. laws stipulate an average of five months jail time for being caught with weed.

It’s much the same split between what we want and what we get for those charged with selling marijuana.

In much of Addiction Now’s polling, the public leans more toward probation than the laws do. It’s likely that probation seems gentler, and maybe it is, but it also has its own dark side. Some judges hand out life-ruining, long-term, consecutive probations that seem to never end, as in the case of rapper Meek Mill.

Meth

For users of methamphetamine, the gap between the public and courts isn’t so extreme, with most respondents, 31%, preferring sentences of 13 months of probation and alternatives. “Alternatives” throughout the Addiction Now survey includes:

- residence in a community treatment center

- home detention

- community service

- curfew

- some custody

For dealers though, Americans and judges are on the same page as far as the form of punishment goes, if not its duration. 46% of the former suggest 66 months in jail and the latter actually hand out 96 months of cell time.

Cocaines

Let’s do these together:

- crack cocaine

- powdered cocaine

It’s felt by many that the first one is the drug of choice for non-whites and people with less money, while the powdered stuff is more often associated with the white-collared. There may be evidence of this in the difference between the amounts of time in jail for possession of either drug. With crack, one can expect to be inside for 18 months, for powered, just five. The same is true for selling, with those convicted of trafficking in powdered cocaine serving 10 months less time.

What the public expects for using either crack or powder cocaine is roughly the same: 30-31 months of probation and alternatives.

Heroin

Maybe it’s all the bad publicity meth gets—or socio-economic or race bias—but amazingly, infamously hard drug heroin seems to elicit a less harsh reaction than methamphetamines in this survey. It’s a more suburban, upper-middle-class drug these days. In trafficking, things are even fishier: Less time in jail both according to the public and the courts. Hm.

So, what would we do with prisoners if we fixed this?

Addiction Now also asked people what kind of reparations, if any, should be made to those who are languishing behind bars now or who’ve done so in the past.

As with the earlier racial discrimination question a majority of all political affiliations—except Republicans—said pardons for those wrongly jailed are in order. Beyond that, for all other questions, there’s general agreement except for the one asking if the government should financially compensate the offenders, with, again, Republicans being least enthusiastic about the idea.

So

There’s definitely a gap here between the sentences Americans think are reasonable and what the courts hand down. In the face of an accelerating opioid epidemic, it’s incumbent upon us to analyze all of the data that’s been collected to ascertain the best ways of restoring drug offenders to productive paths. One thing we know: It’s not about building more prisons.