Why the First Amendment may protect 3D-printed guns

August 1, 2018, was supposed to usher in ‘the age of the downloadable gun,’ according to Defense Distributed, which received permission last month to resume distributing online blueprints for 3D-printable guns after settling a legal battle with the U.S. Department of Justice.

But that’s on hold for now following a fierce legal battle that resulted in a judge temporarily blocking the company from distributing the controversial files. It’s a battle that Defense Distributed founder Cody Wilson considers to be about “access to information,” not gun regulations.

“What I’m doing is legally protected,” Wilson told CBS News. “I’m talking about files. I’m not talking about the guns. I’m not a licensed gun manufacturer. I don’t make guns at this location. I have data, I can share the data.”

Some see it differently.

“Let me be clear, it’s not about the First Amendment,” said New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal, one of 21 attorneys general who filed a joint lawsuit attempting to block Defense Distributed from publishing its files. “What this case is about is public safety. We are trying to keep untraceable guns out of the hands of individuals who cannot own them.”

Gun-control supporters have criticized Defense Distributed for promoting unfettered access to firearms, including 3D-printed handguns and AR-15 assault rifles. The company does theoretically want to make these plans available to everyone—Wilson is a self-described ‘crypto-anarchist’, after all. But actually manufacturing the guns would require an expensive 3D printer and a milling machine, not to mention the interest to make your own (mostly) plastic gun.

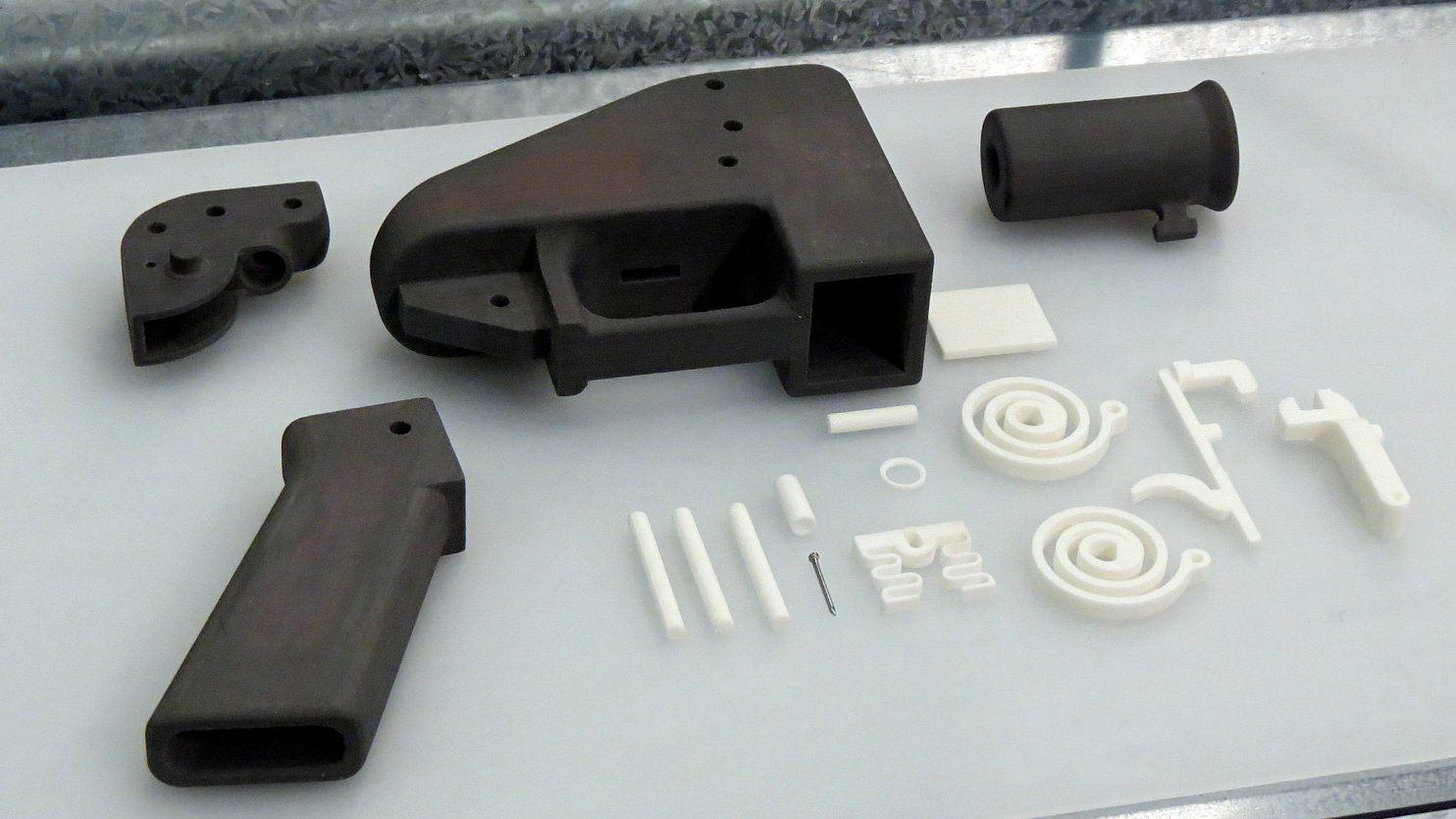

The Liberator (Photo: KELLY WEST/AFP/Getty Images)

Others, including supporters of both the First and Second Amendments, argue that these plastic guns don’t constitute a significant threat, that the DIY gun-making community has been around for decades, and that the government shouldn’t be in the business of regulating computer code in the first place.

Many complex legal questions will likely emerge from 3D-printed guns, but for now the fundamental question for the courts is seemingly simple: is code speech?

In the U.S. legal system, there’s a long history of courts trying to sort out which forms of expression constitute speech. They have in the past, for instance, decided that activities like flag burning and nude dancing constitute acceptable forms of speech, and are therefore protected by the First Amendment. More recently, in Citizens United v. FEC, the Supreme Court ruled that campaign donations are a form of political speech, and therefore not subject to previous restrictions.

The key question now is whether computer code—the ones and zeros that form something as innocuous as video games or as malicious as a computer virus—should be considered speech.

Some lower courts have already treated it as such. In Universal City Studios v. Corley (2000), a case from 2000 about the legality of distributing software (and its source code) capable of decrypting copyrighted content, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals wrote that computer programs are a form of protected speech.

“Computer programs are not exempted from the category of First Amendment speech simply because their instructions require use of a computer,” the court’s opinion reads. “A recipe is no less “speech” because it calls for the use of an oven, and a musical score is no less “speech” because it specifies performance on an electric guitar.”

In Bernstein v. United States (1996), the federal government tried to block a cryptographer from publishing the source code (and other information) of an encryption program, which the government classifies as munitions. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that software source code was speech protected by the First Amendment.

Bernstein is particularly relevant: The cryptographer Daniel Bernstein, like Defense Distributed, was simply trying to distribute information that developers could use to build a product. He wasn’t trying to distribute the product itself. After all, the manufacture and distribution of unregistered firearms is not protected by the Second Amendment.

(Photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

This, however, is a First Amendment issue. The government cannot necessarily restrict speech just because it could lead to violence. Case in point: ‘The Anarchist Cookbook’ has been on shelves in U.S. bookstores since 1971 even though it contains instructions on how to make simple bombs and Molotov cocktails. Explaining how to commit violence, or even advocating for it at some indefinite future time, isn’t illegal.

However, speech can be restricted if it’s likely to incite crime soon.

In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the Supreme Court established the ‘imminent lawless action’ standard that defined, in part, the limits of free speech. According to the standard, speech isn’t protected by the First Amendment if it’s both trying to incite lawless action and likely to produce such action imminently.

The digital distribution of 3D gun files would almost surely not violate the imminent lawless action standard. Also, because banning such files would amount to a ‘content-based’ restriction, the government would have to demonstrate a compelling state interest in the ban and that the ban is narrowly tailored, using the least restrictive means to achieve it.

As Noah Feldman wrote for Bloomberg, “The government might conceivably have a compelling interest in prohibiting the manufacture of unregulated guns, but there are so many guns already being made that this argument isn’t a sure winner.

“In any case, the ban probably isn’t narrowly tailored enough, because the government can prohibit the actual act of printing—a prohibition that would be much more narrowly tailored to the evil of the guns than a ban on how they can be printed. So the Supreme Court would probably consider a ban on distributing the code to violate the First Amendment.”

But the courts have yet to deal directly with the First Amendment implications of 3D gun files. Rather, the U.S. Department of Justice simply reached a settlement with Wilson that, while indicative of the goalposts in this legal gray zone, doesn’t quite amount to setting legal precedent.

It’s also unclear if Wilson’s “the age of the downloadable gun” will be ushered in anytime soon, considering a federal judge granted a temporary nationwide injunction blocking him from publishing the gun blueprints.

Judge Robert S. Lasnik of United States District Court for the Western District of Washington said there were “serious First Amendment issues” that need sorting out, but for now there should be “no posting of instructions of how to produce 3-D guns on the internet.”