Ethan Siegel

A theoretical astrophysicist and science writer, host of popular podcast "Starts with a Bang!"

Ethan Siegel is a Ph.D. astrophysicist and author of "Starts with a Bang!" He is a science communicator, who professes physics and astronomy at various colleges. He has won numerous awards for science writing since 2008 for his blog, including the award for best science blog by the Institute of Physics. His two books "Treknology: The Science of Star Trek from Tricorders to Warp Drive" and "Beyond the Galaxy: How humanity looked beyond our Milky Way and discovered the entire Universe" are available for purchase at Amazon. Follow him on Twitter @startswithabang.

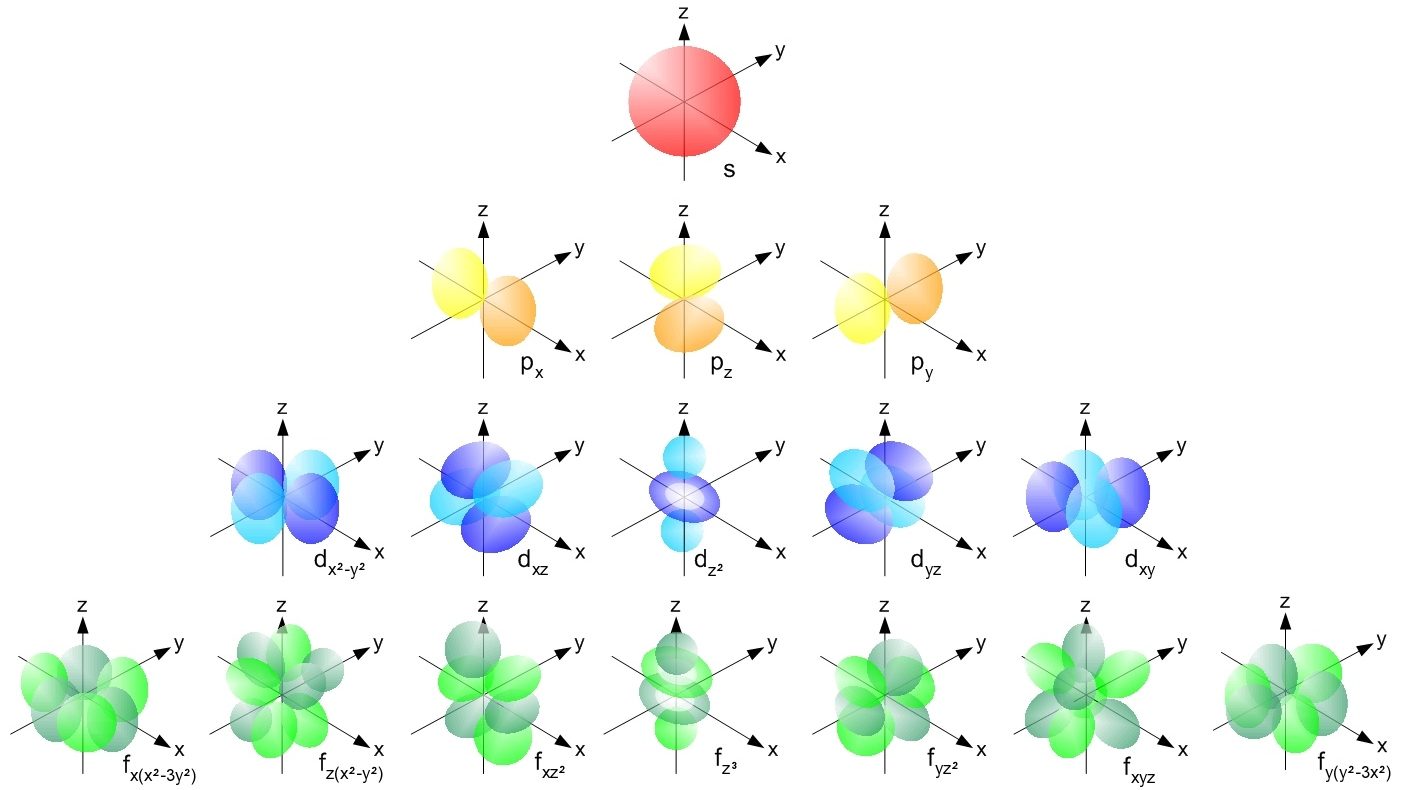

If atoms are mostly empty space, then why can’t two objects made of atoms simply pass through each other? Quantum physics explains why.

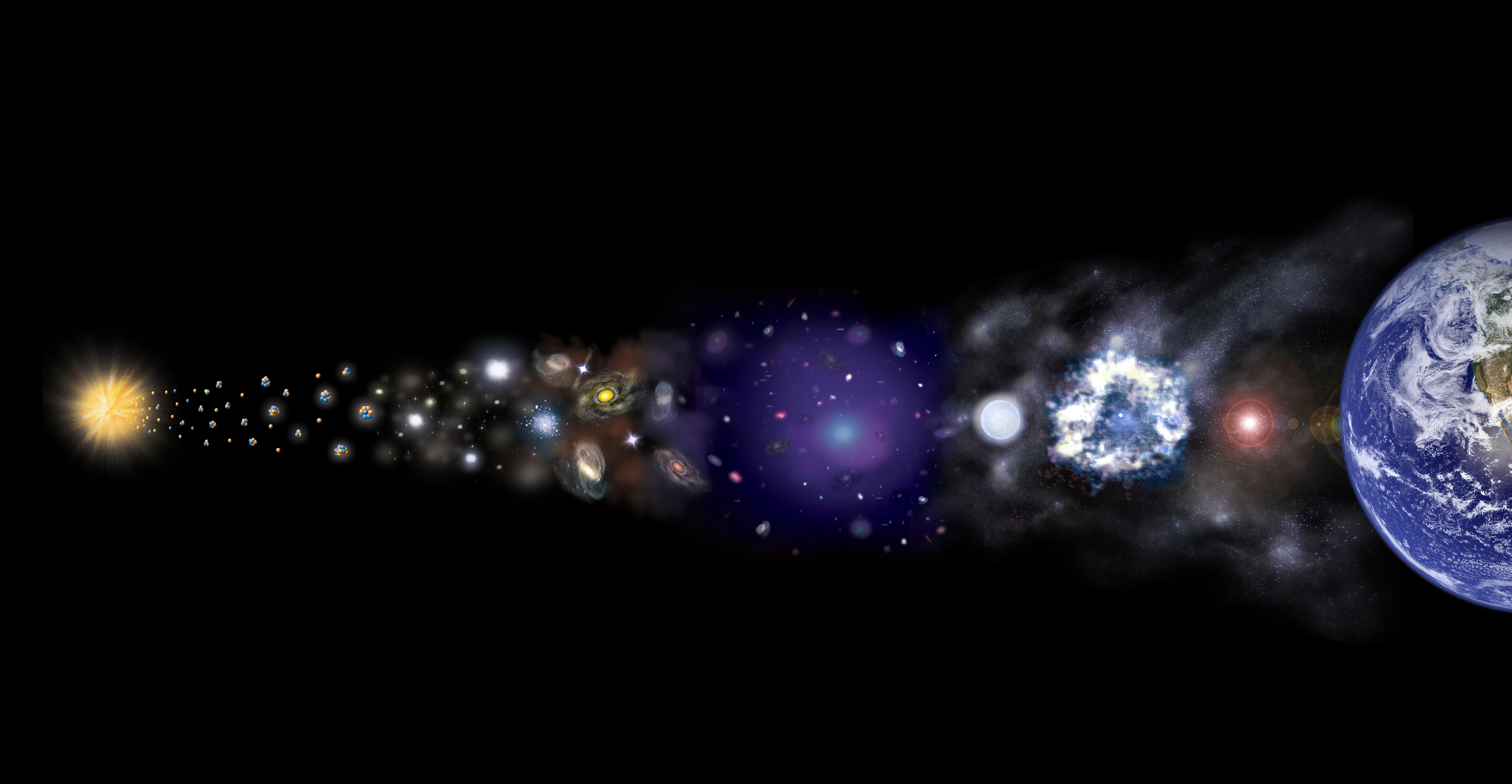

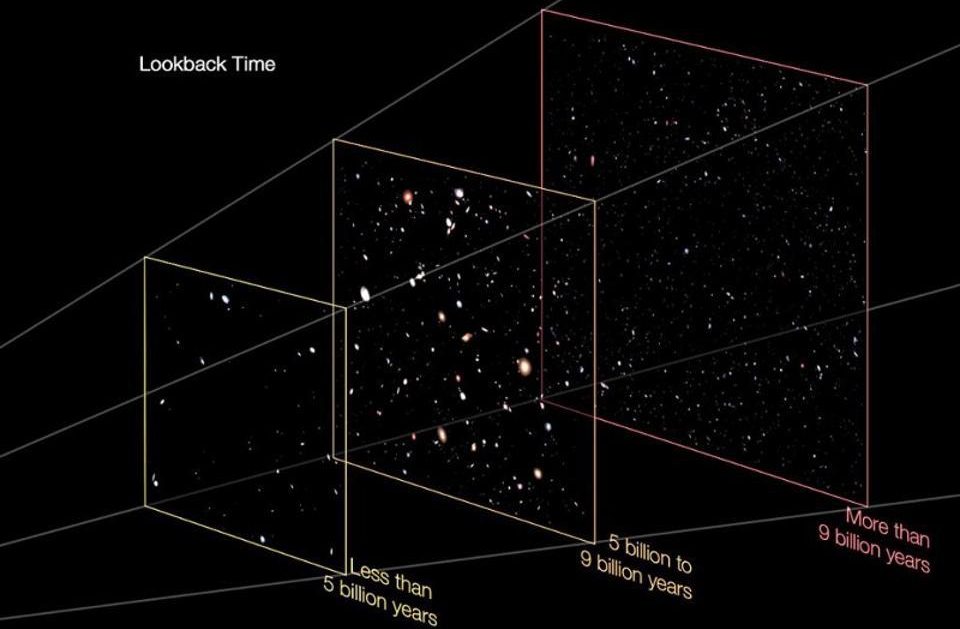

From a hot, dense, uniform state in its earliest moments, our entire known Universe arose. These unavoidable steps made it all possible.

It was barely a century ago that we thought the Milky Way encompassed the entirety of the Universe. Now? We’re not even a special galaxy.

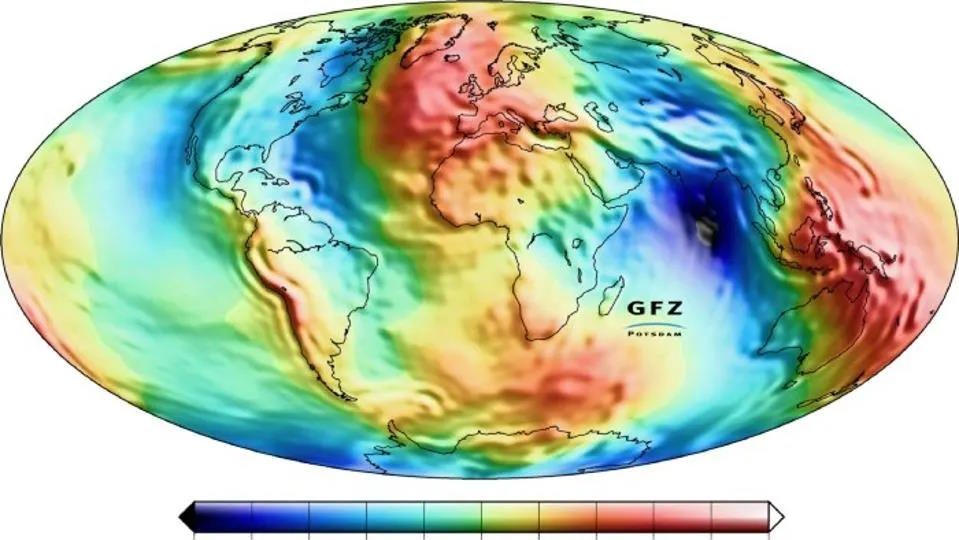

Even with just a momentary view of our galaxy right now, the data we collect enables us to reconstruct so much of our past history.

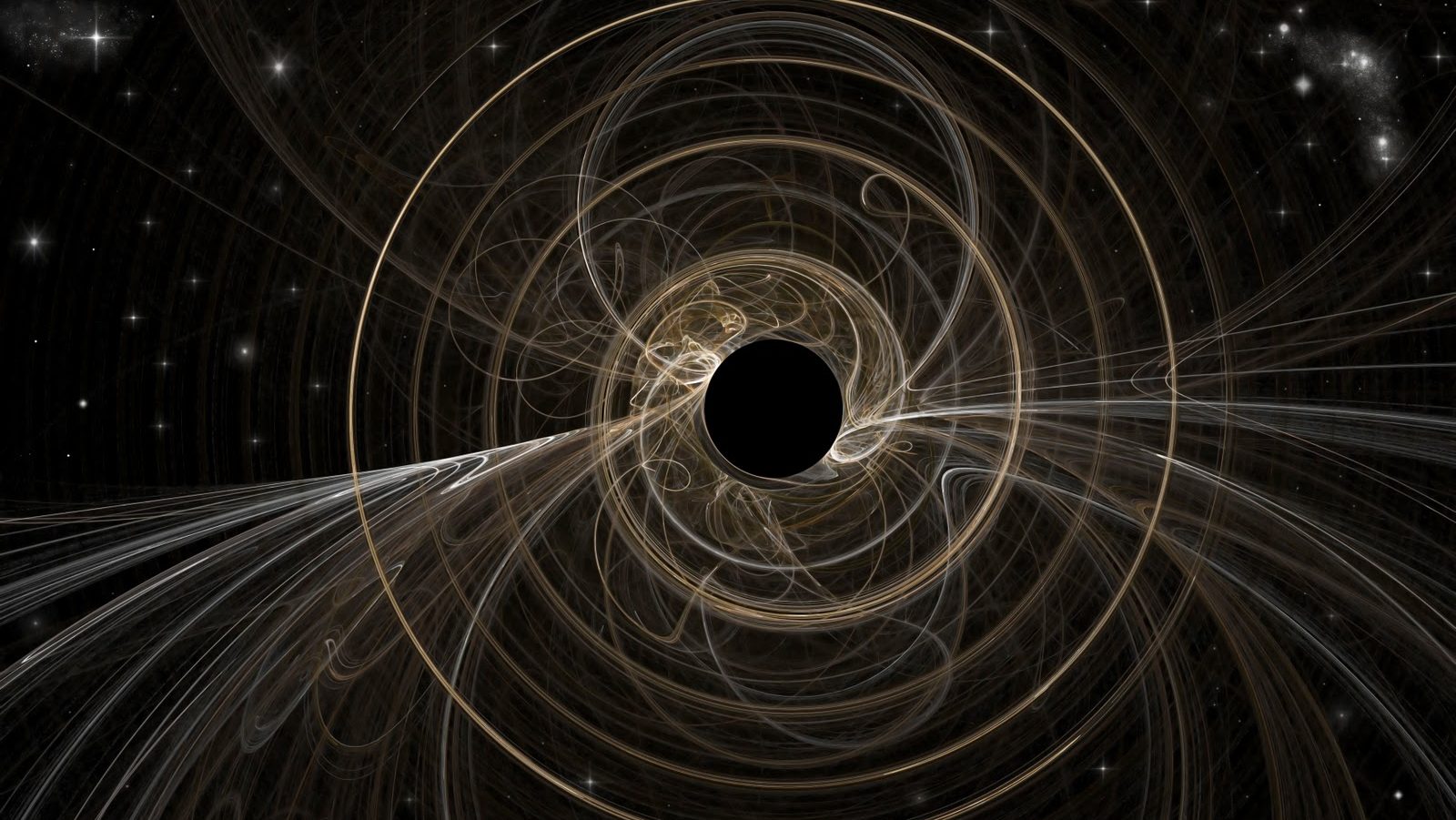

50 years ago, Stephen Hawking showed that black holes emit radiation and eventually decay away. That fate may now apply to everything.

The closest known star that will soon undergo a core-collapse supernova is Betelgeuse, just 640 light-years away. Here’s what we’ll observe.

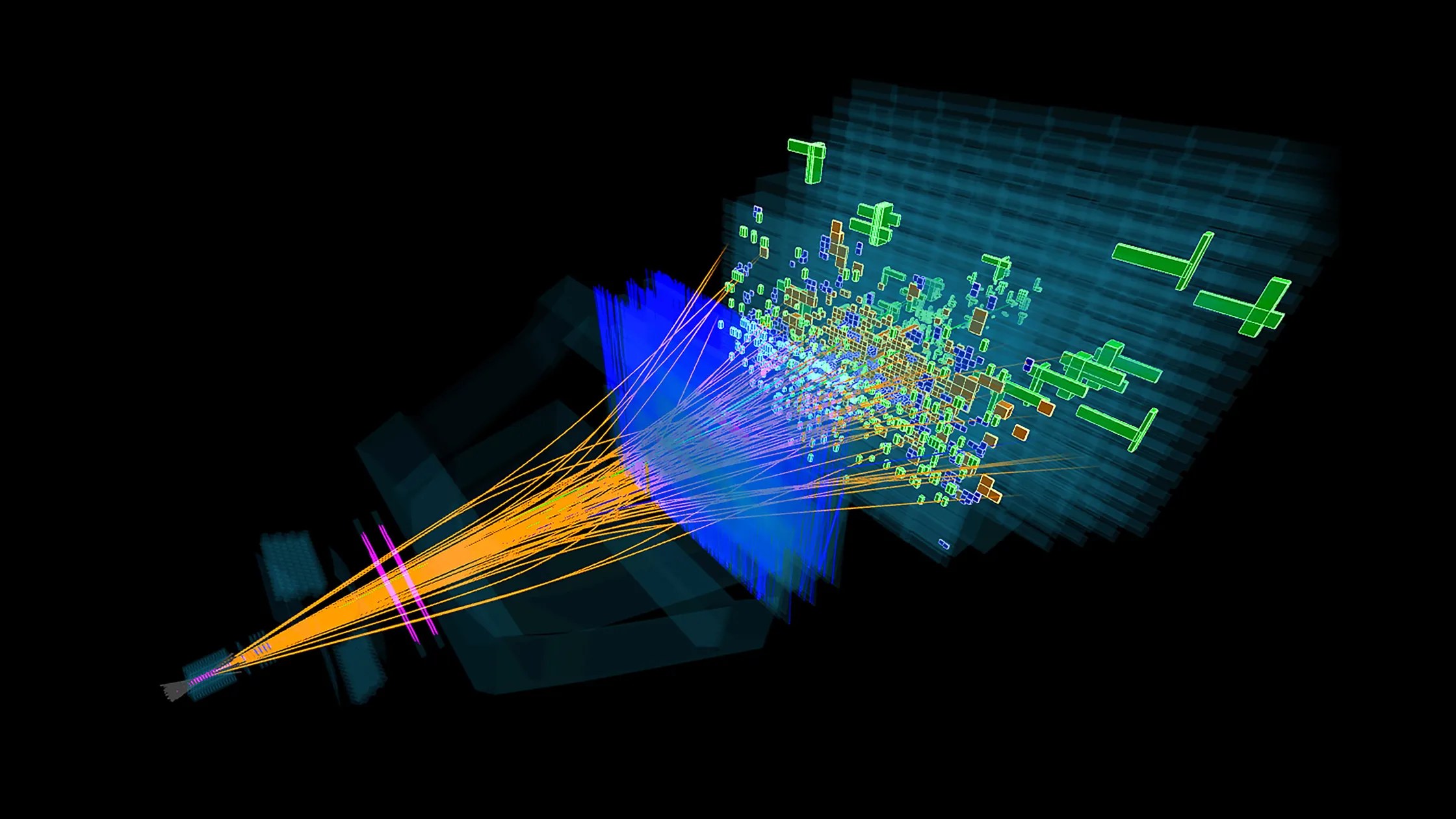

We have very specific predictions for how particles ought to decay. When we look at B-mesons all together, something vital doesn’t add up.

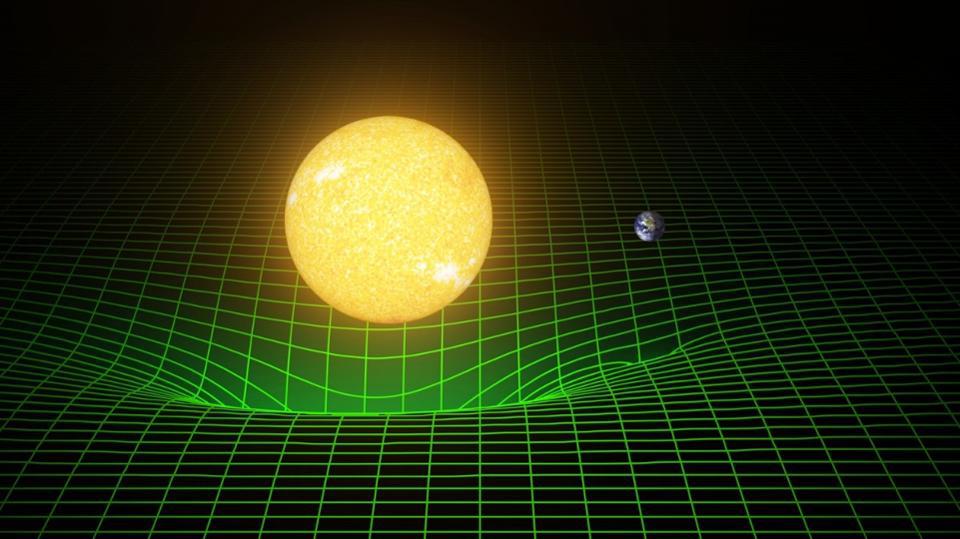

Most waves need a medium to travel through. But the way that light and gravitational waves travel shows that space can’t be a medium at all.

The Sombrero is the closest bright, massive, edge-on galaxy to us. JWST’s new image, taken with MIRI, finally shows what’s under its hat.

One of the fundamental constants of nature, the fine-structure constant, determines so much about our Universe. Here’s why it matters.

Gravitational waves are the last signatures that are emitted by merging black holes. What happens when these two phenomena meet in space?

For nearly 60 years, the hot Big Bang has been accepted as the best story of our cosmic origin. Could the Steady-State theory be possible?

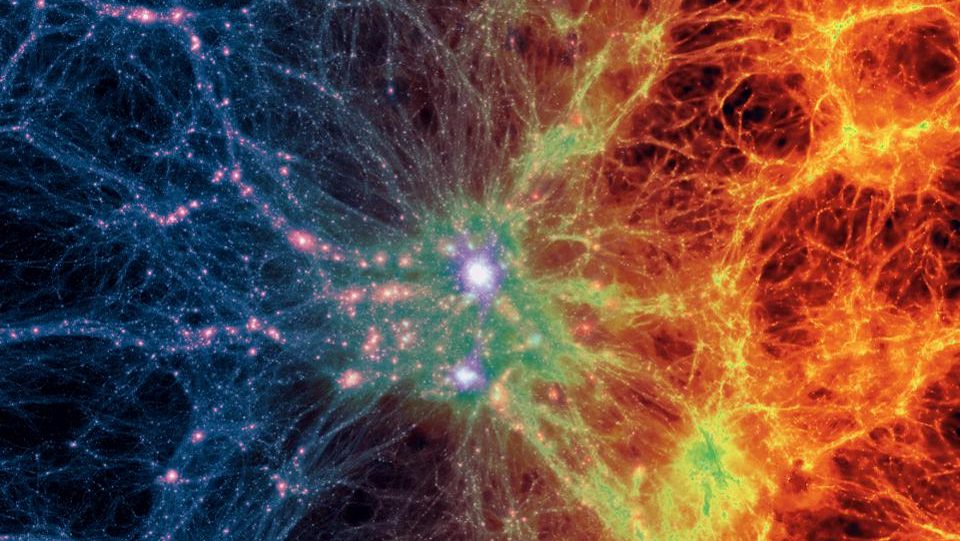

Two parts of our Universe that seem to be unavoidable are dark matter and dark energy. Could they really be two aspects of the same thing?

Scalars, vectors, and tensors come up all the time in physics. They’re more than mathematical structures. They help describe the Universe.

Since the mid-1960s, the CMB has been identified with the Big Bang’s leftover glow. Could any alternative explanations still work?

Our classical intuition is no good in a quantum Universe. To make sense of it, we need to learn, and apply, an entirely novel set of rules.

It’s the ultimate setup for a Thanksgiving Day disaster. The physics of water and its solid, liquid, and gas phases compels us not to do it.

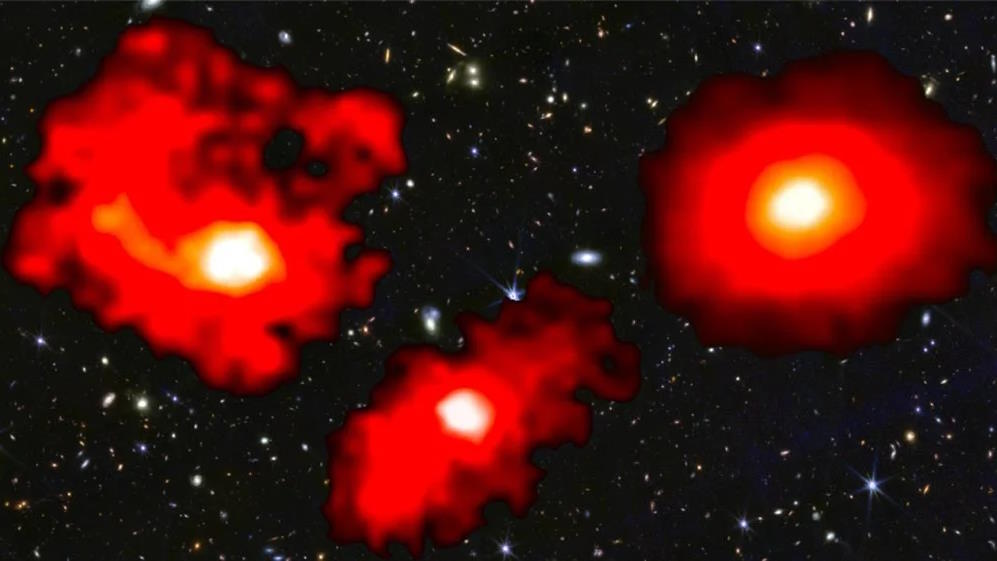

The most massive early galaxies grew up faster, and have more stars, than astronomers expected, according to JWST. What does it all mean?

There are a few small cosmic details that, if things were just a little different, wouldn’t have allowed our existence to be possible.

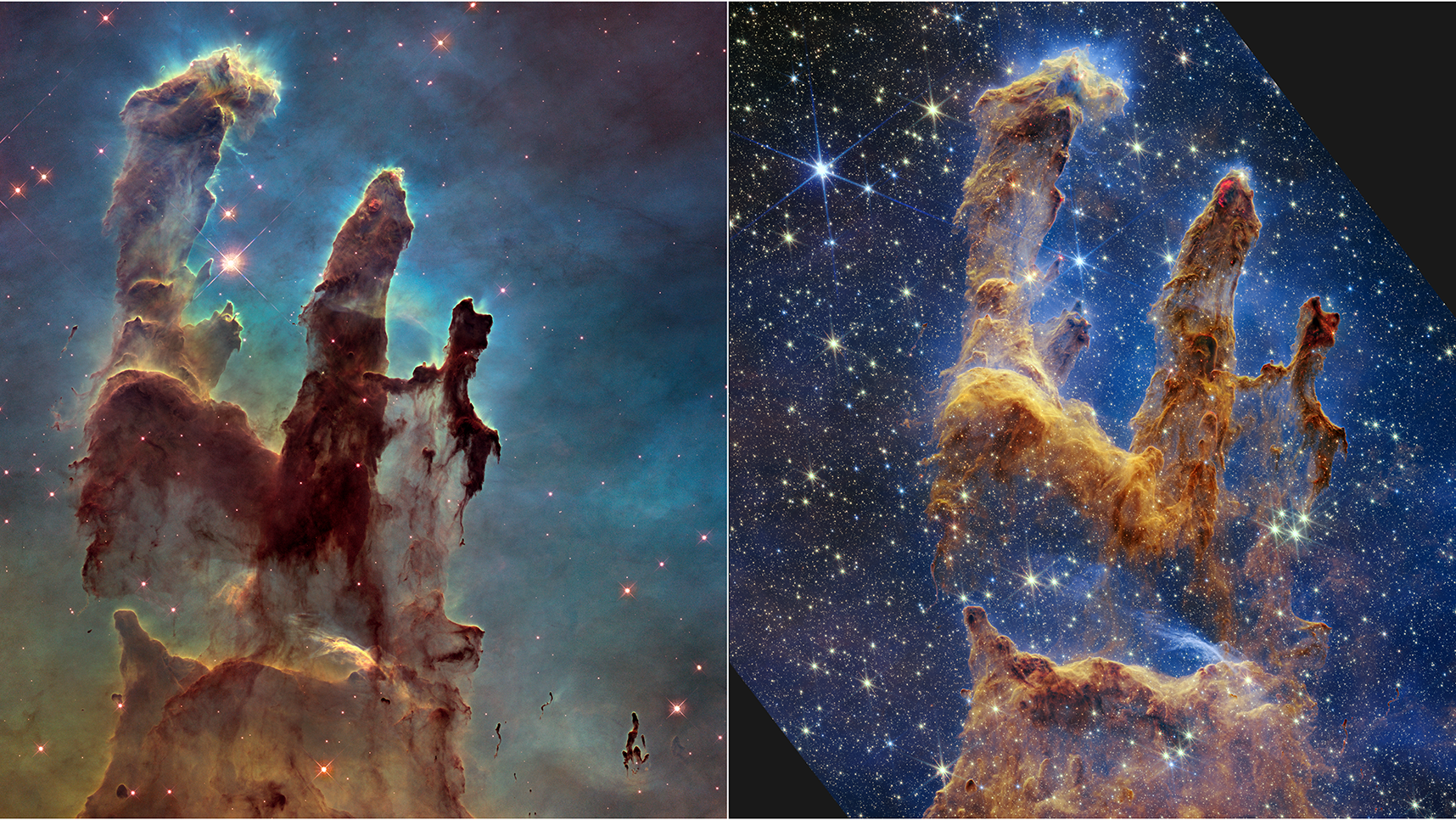

When we see pictures from Hubble or JWST, they show the Universe in a series of brilliant colors. But what do those colors really tell us?

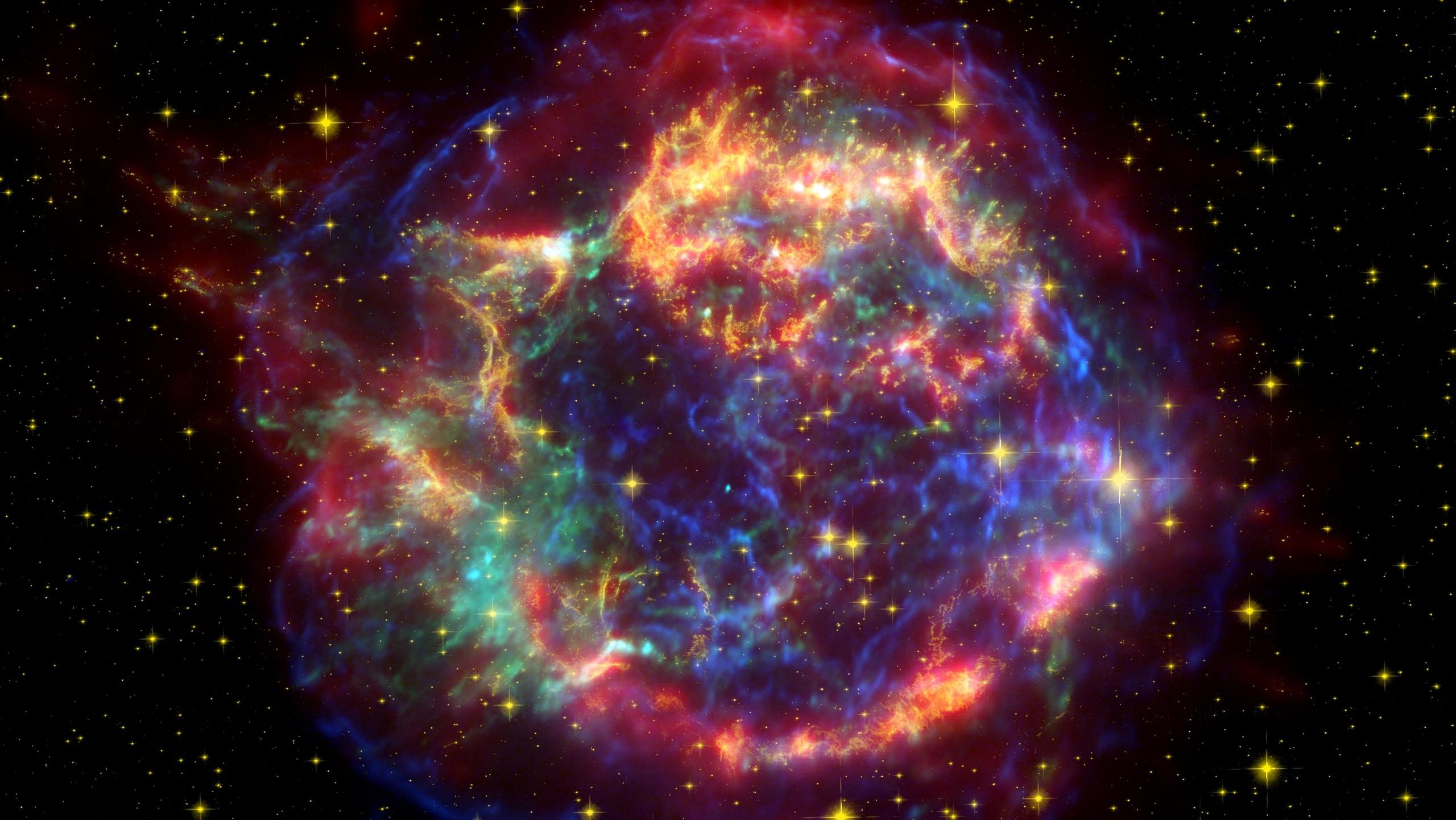

The last naked-eye Milky Way supernova happened way back in 1604. With today’s detectors, the next one could solve the dark matter mystery.

Since 1930, type Ia supernovae have been thought to arise from white dwarfs exceeding the Chandrasekhar mass limit. Here’s why that’s wrong.

In partisan political times, recognizing the scientific truth is more important than ever. Scientists must be vocal and clear about reality.

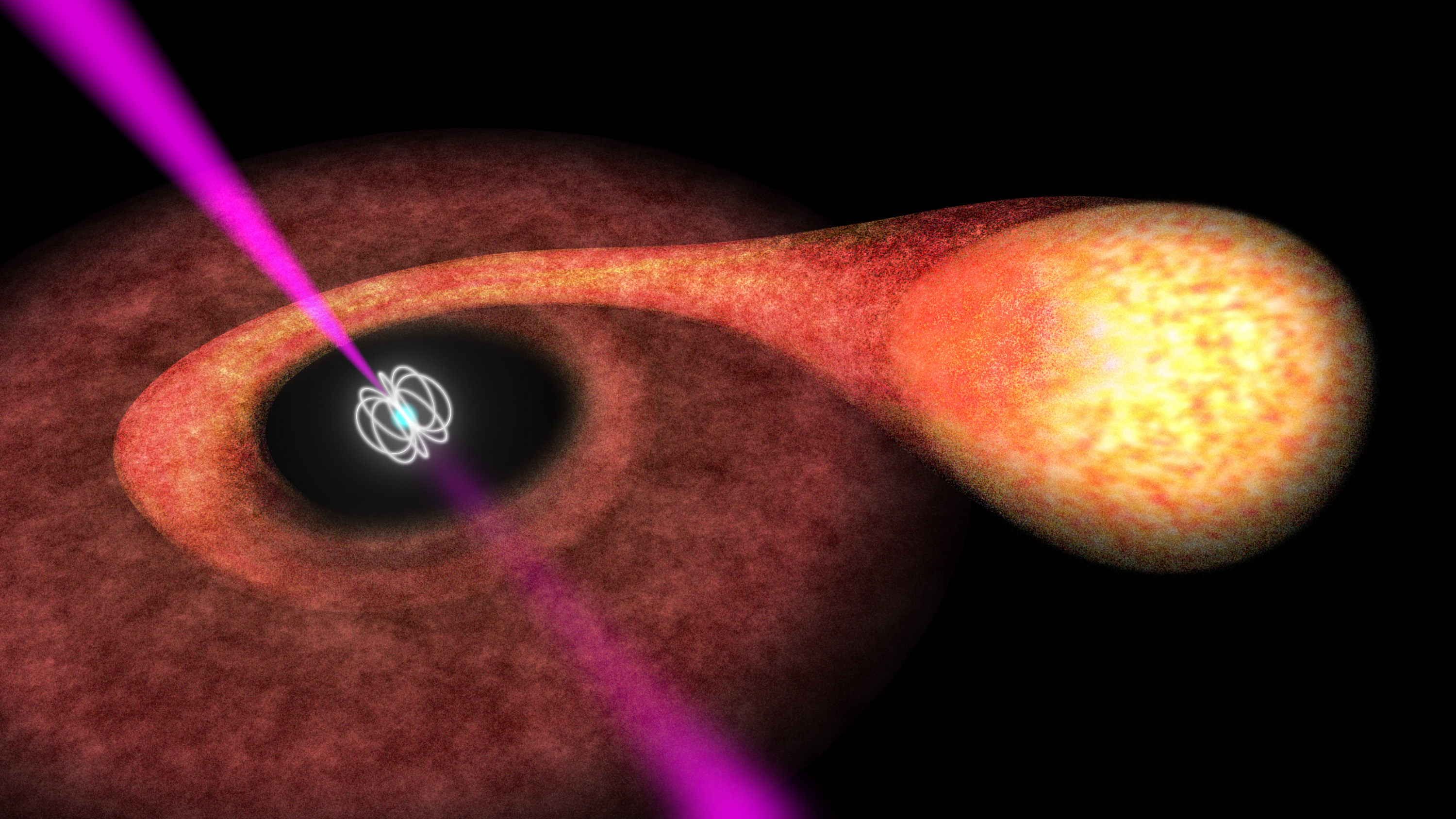

In astronomy, a star’s initial mass determines its ultimate outcome in life. Unless, that is, a stellar companion alters the deal.

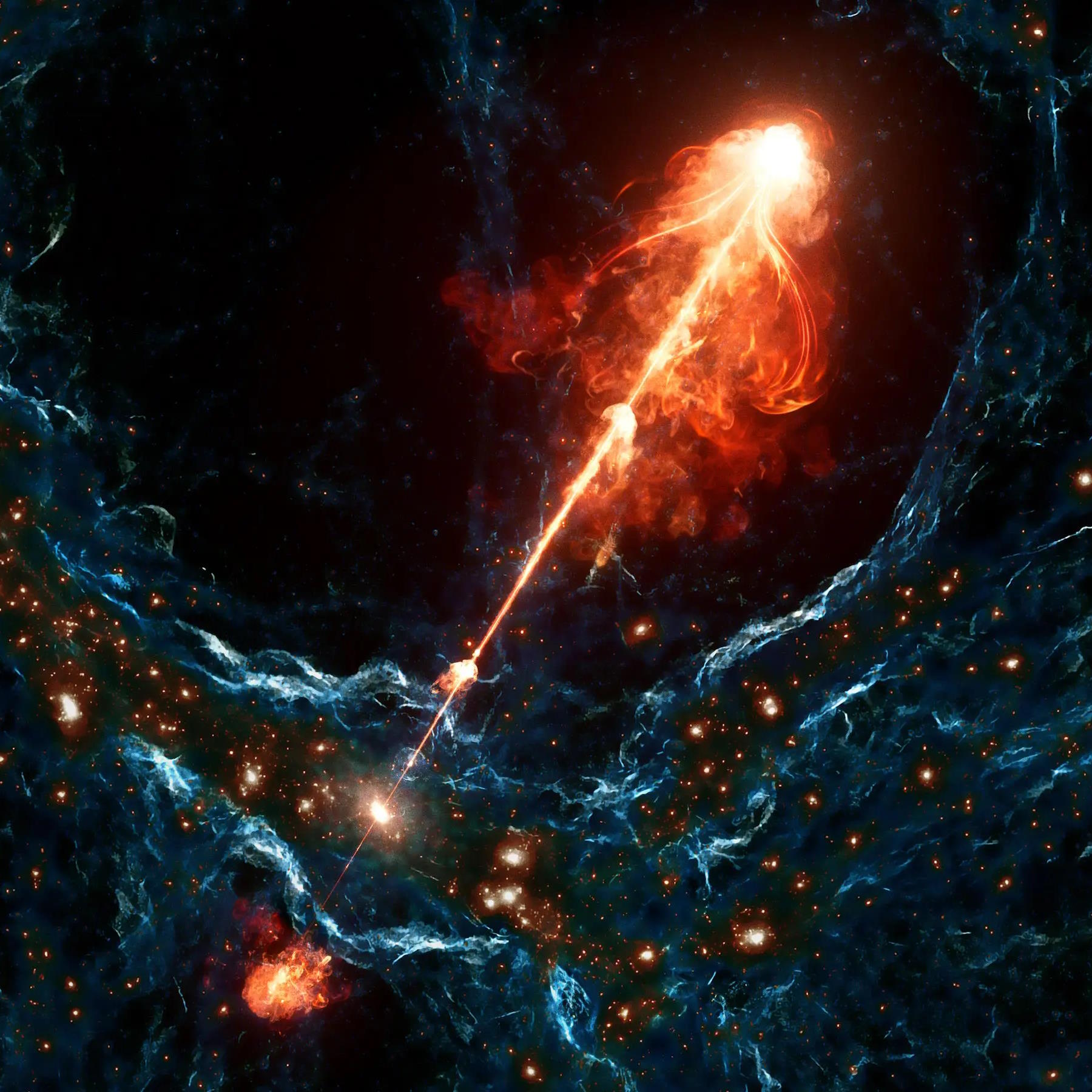

Black holes are the most massive individual objects, spanning up to a light-day across. So how do they make jets that affect the cosmic web?

Humans, when we consider space travel, recognize the need for gravity. Without our planet, is artificial or antigravity even possible?

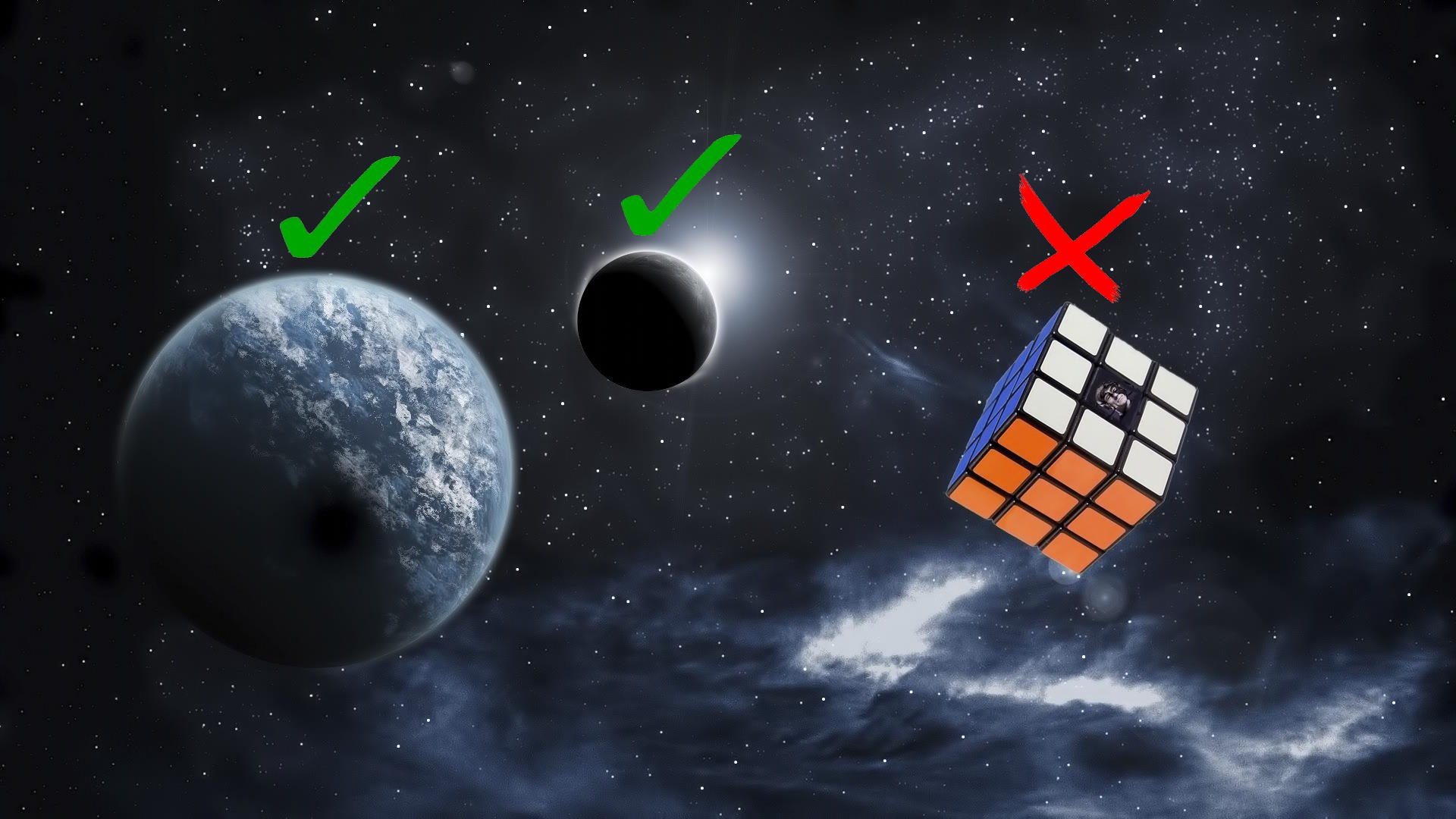

All the stars, stellar corpses, planets, and other large, massive objects take on spherical or spheroidal shapes. Why is that universal?

A crowdsourced “final exam” for AI promises to test LLMs like never before. Here’s how the idea, and its implementation, dooms us to fail.

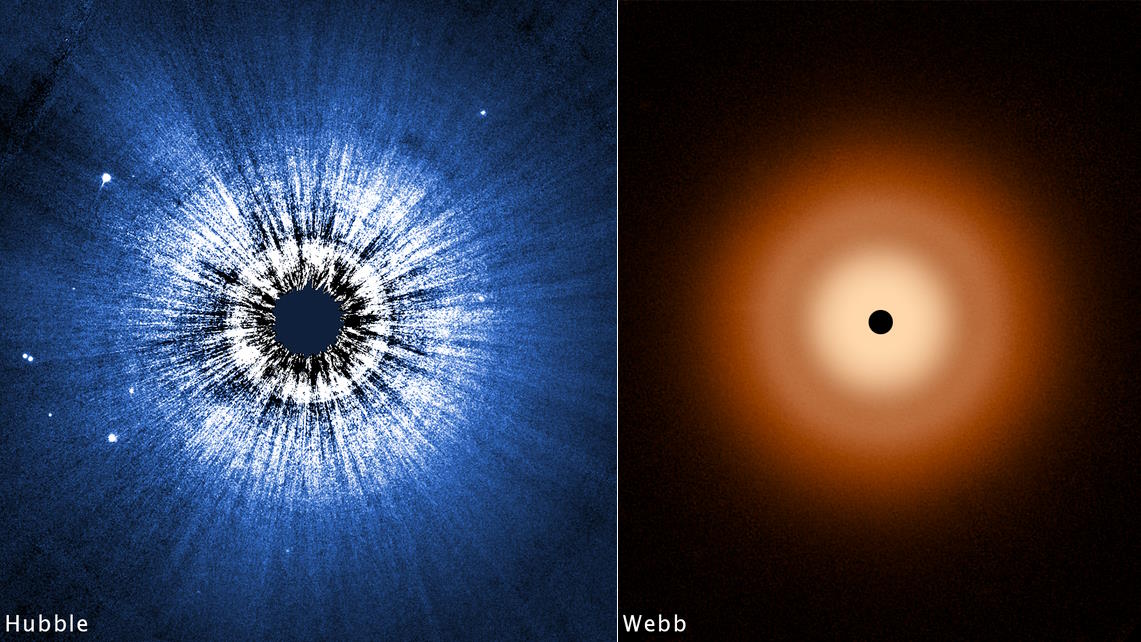

The 5th brightest star in our night sky is young, blue, and apparently devoid of massive planets. New JWST observations deepen the mystery.

Whether your hair is straight, wavy, curly, or kinky isn’t just genetic in nature. It depends on the physics of your hair’s very atoms.