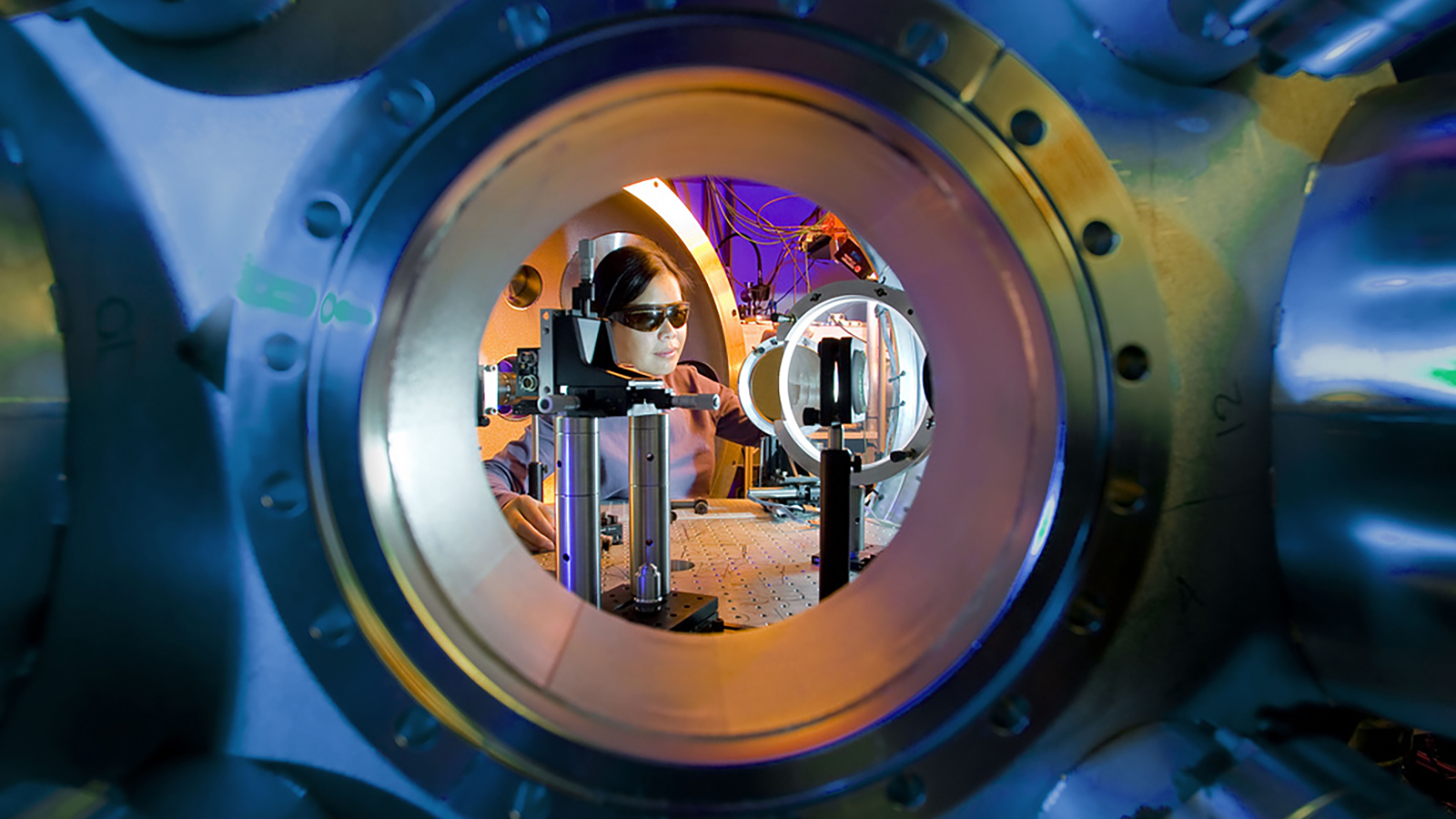

Where Are All the Women Scientists?

“My course is so clear and obvious that it is delightful to think how straight it is. And yet what a mountain I have to climb! It is enough to frighten anyone who had not all that most insatiable and restless energy.” – Ada Lovelace, the world’s first computer programmer, in a letter to her mother

What’s the Big Idea?

There is a distinct moment in many a girl’s education when she wakes up wanting to be a novelist. Or a singer, or a fashion designer – not because she feels called by any particular creative passion, but because she is so discouraged about the grade she received on her last math test that she can’t conceive of her self as capable of doing anything else. Even the undeniably-brilliant First Lady quipped recently in an address to the National Science Foundation, “Me? I’m a lawyer because I was bad at math and science. It’s what you opt out for.”

Obama’s address to the National Science Foundation starts at 12:00.

Of course there’s nothing wrong with a long, financially-dependent life in the liberal arts, but there is something amiss when you’ve decided – or been told – that you’re just no good at math and science before you’ve hit fifteen. As teachers and parents will attest, whatever sociological forces are dividing women and men into paths as nurses or radiologists, daycare providers or professors, they are in full swing by high school.

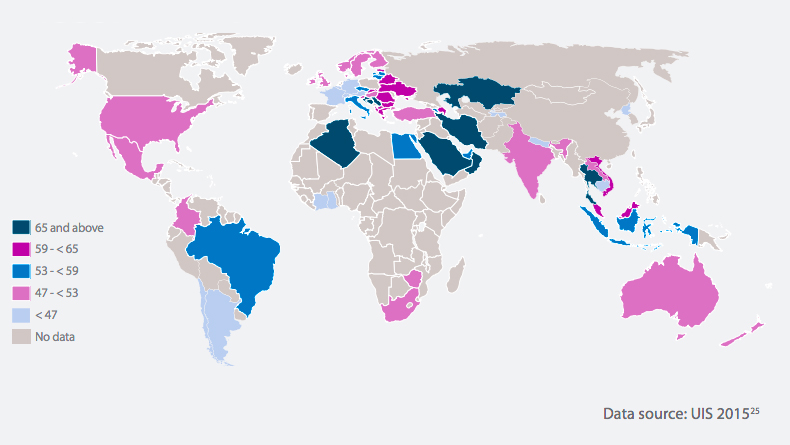

Often, the persistent under-representation of women in science is chalked up to “issues of intrinsic aptitude” or self-esteem. (Try telling that to French women, who not only don’t get fat, but also earn 1/3 of physics degrees in France, as compared to 13% by their American counterparts.) But even in today’s world of pink wristbands and girl power, the real problem is external factors, rather than an inner lack of motivation or confidence. “Only a handful of [elite] schools” are actually giving girls the support they need to succeed,” says says Dr. Sian Beilock, PhD.

And what happens when a girl does decide to go in to a science, tech, engineering, or math-related (STEM) field, despite the challenges? According to neuroscientist Joy Hirsch, female undergrads are dropping STEM majors at an alarming rate. “In college, many of the fields now start out with a 50/50 distribution of women to men. But by the time you get to the ranks of tenured professor, only 15 to 20 percent have remained.”

Where do all the women go?

“It’s easy to give explanations about, you know, life’s complexities, family, etc., etc., etc. But that doesn’t explain it if you as the women who started out in the trajectory and didn’t make it,” says Hirsch. And the problem isn’t with the women – who, after all, had ambition and talent enough to apply and gain acceptance in the first place.

It’s also not about maintaining distance from or feeling discomfort around male colleagues. “I like working with men,” says Hirsch. That being said, she has no hesitation “reporting experiences of pretty extraordinary discrimination.”

If your paper is being reviewed, maybe reviewers want a little more evidence because there’s some doubt about a woman scientist. If you’re up for tenure, there is a bit more scrutiny because the letters about a woman don’t say the things that a tenure committee wants to hear. A powerful leader of the field is not usually a descriptor for a woman. Oftentimes a woman is described in terms of her excellent teaching ability and her mentoring, but that’s not considered the attribute that leads to leadership and scientific advances.

What’s the Significance?

These types of events are benign, “in that they are not intentional.” But they have a way of adding up, with the ultimate effect of discouraging women from pursuing the publications and associations that result in prestige, awards, and power. “At every single decision point that a woman scientist has, she is a little bit more vulnerable,” says Hirsch. And while some argue that lack of interest is the reason why few women join selective organizations and win scholarly prizes – less than 5% in some cases – “the data show under-recognition of women even after adjusting for their lower participation in most STEM fields.”

Clearly, the language of individual empowerment only goes so far. The fact that it took Harvard 375 years to tenure its first female math professor is enough to suggest that a broader, systemic evaluation is in order. But “if you love science and if that’s what you want to do,” that won’t stop you. “You have to learn when not to be too much of a lady. If you have to kickass, just go do it. And that’s what women are going to have to do; they’re going to have to face that once in a while that you just sometimes gotta be tougher than you are.”

Woman teaching geometry

Ed. note: The Obama quote should read, “Me? I’m a lawyer because I was bad at these subjects [math and science]. It’s what you opt out for.”