7 disastrous encounters with the world’s most hostile uncontacted tribe

- For more than a century, many people have tried to contact the Sentinelese.

- By all accounts, however, the inhabitants of the 23-square-mile island in the Bay of Bengal don’t want anything to do with the outside world.

- The size of the population is unknown, but it’s estimated that between 40 to 500 remain.

Between waves of refugees, armed conflicts, and bickering over oil reserves, the world feels like it’s become a rather small place. But while the world may be shrinking, some people are still fighting to keep a little space to themselves. North Sentinel Island is a perfect example.

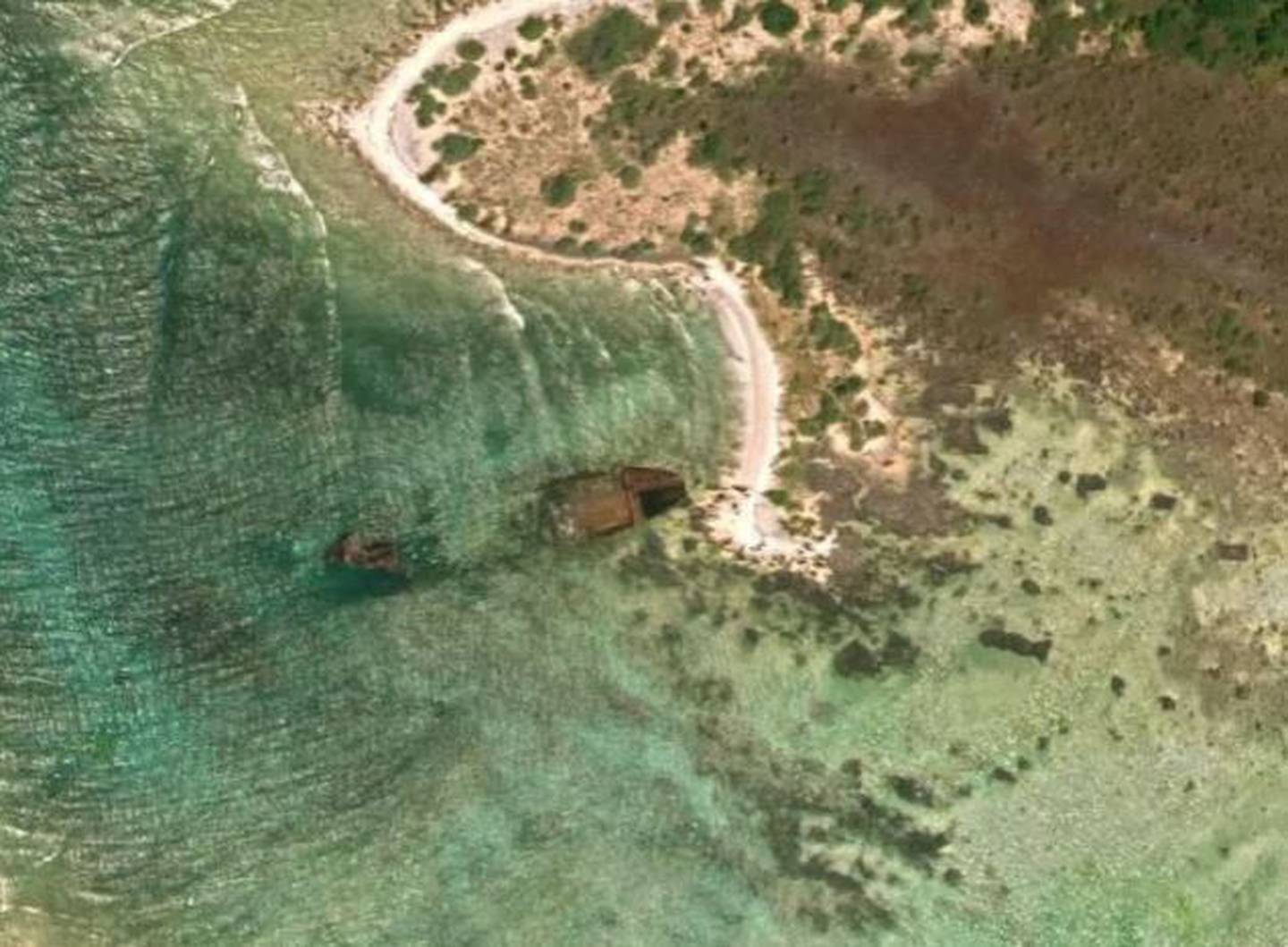

The island has an area of about 23 square miles and is surrounded by a natural barricade of coral reefs. Located east of India in the Bay of Bengal, the island is home to one of the very last uncontacted tribes on the planet. There are between 40 and 500 members of the Sentinelese living on the island, though it’s impossible to estimate the exact numbers.

The Sentinelese are perhaps the most aggressive uncontacted tribe that exists. Nearly every attempt at contact has ended in disaster and sometimes death. Below are seven accounts of such attempts.

1880: The British Empire’s famous hospitality

During their imperialist period, the British had something of an unusual protocol when it came to unfriendly tribes. If a tribe refused to be contacted or were aggressive toward British colonists, they would kidnap a member of the tribe, supply the prisoner with gifts and treat them well, and free their captive shortly after. In theory, the captive would return to the tribe with reports of generous (if somewhat socially inept) outsiders.

This is the approach that Maurice Vidal Portman took during one of the first explorations of the island. At first, the Sentinelese fled into the jungle at the approach of Portman and his men. Eventually, they stumbled across an elderly couple and some children who couldn’t flee fast enough.

As if this kidnapping protocol wasn’t bad enough, Portman decided to abduct these elderly people and children. The elderly Sentinelese couple soon grew ill, likely because Portman and his men were carrying a variety of Western diseases that had never reached the island before. In a few days, the couple had died.

The British gave the children a variety of gifts for the tribe and released them back into the jungle minus two grandparents. It seems unlikely that the Sentinelese appreciated this. After this first point of contact, the tribe were more overtly hostile to outsiders.

1970: India explores its new lands

When India gained its independence from Britain, many islands in the area were handed over to India as well, including North Sentinel Island. A few decades later, India decided to make contact with the Sentinelese, using a more scientific and gentler approach than the British.

They made a series of attempts at contact, each headed by the anthropologist Triloknath Pandit. Armed police and naval officers joined Pandit for protection. For the most part, the group would observe the islanders from the safety of boats moored far from the shoreline.

In 1970, however, Pandit’s ship strayed too close to the beaches of the island. Several men from the tribe began aiming their bows at the boat, shouting, and behaving aggressively. Pandit reported that several of them squatted on their haunches as though they were defecating. He read this as a kind of insult.

As if this wasn’t unusual enough, women quickly emerged from the tree line and paired off with each man on the beach. Each couple embraced passionately in what appeared to be a mass mating display. Under these conditions, the hostile atmosphere evaporated, the tribe eventually returned to the forest, and Pandit’s expedition returned to India.

1974: National Geographic attacked

By now, knowledge of the elusive tribe had spread far enough that National Geographic sent a crew there to film a documentary. As the National Geographic boat crossed through an opening in the island’s reef barrier, they were greeted with a hail of arrows.

This barrage missed the boat, which pressed on toward the shore despite the assault. The police who accompanied the documentary crew landed on the shore and left a series of gifts for the Sentinelese in the hopes that future encounters would be on friendlier terms. The gifts were an unusual mix of the useful and potentially amusing: aluminum cookware; a toy car; coconuts; a doll; and a live, tied-up pig.

As the police deposited the crew’s gifts on the shore, another volley of arrows issued from the tree line. This time, the documentary’s director was struck in the thigh, and the crew rushed back to their boats. Crew members reported that the man who shot the arrow laughed proudly while his tribesmen continued the attack until the boats had retreated out of range.

The encounter didn’t end here, however: the crew wanted to see how their gifts were received. The Sentinelese retrieved the cookware and coconuts. In a bizarre act, the man who had shot the documentary director took the pig and doll and buried them in the sand. You can watch some of this footage below.

1981: The plight of the Primrose

In India, August is monsoon season. During one of these windy rainstorms, a freighter ship called the Primrose struck one of the coral reefs that surround North Sentinel Island and was stranded along with its 28 sailors. With little to do but wait, the sailors slept through the storm.

When they awoke the next morning, the captain immediately broadcasted an urgent message to Hong Kong: On the nearby shore of the island, dozens of Sentinelese were aiming their spears and arrows at the grounded ship. The captain asked for an airdrop of weapons to defend themselves. The next day, their situation had worsened. The Sentinelese were constructing boats to sail to the coral reef where the Primrose had run aground.

Because of the strong storms during this season, it was impossible to send an immediate airdrop of firearms. However, this meant that the Sentinelese were also unable to sail out to the Primrose. The crew was stranded off the coast of North Sentinel Island for nearly a week until the weather had cleared enough for a rescue helicopter to arrive and ferry the men off of the ship. As the helicopter made a series of trips to the boat, the Sentinelese fired arrows at it in an attempt to drive it off.

1991: Pandit makes progress

Triloknath Pandit continued to make attempts at contact after his 1970 visit. Finally, in 1991, he had some measure of success. Pandit and his crew landed on the beach and were met by an unarmed group of 28 Sentinelese, a mixture of men, women, and children.

Despite the progress, the Sentinelese made it clear that there were limits to what outsiders could and could not do. Some of Pandit’s crew were resting in a dinghy that had begun to drift away from the island while he remained on shore. Seeing this, one Sentinelese man drew a knife and threatened Pandit with it. This drifting dinghy made it seem like Pandit intended to stay on the island while his companions sailed off, something that the Sentinelese would not tolerate. The dinghy was brought back to shore, and Pandit sailed off again.

Soon after this visit and despite the progress, it was decided that further contact with these people would not be advisable. With a group so obviously inhospitable to the outside world, to force that world upon them would serve neither the Sentinelese nor global community much good. What’s more, continued contact put the Sentinelese at risk. They harbor few defenses against the larger world’s illnesses, as demonstrated by the British’s first attempt at contact in 1880. For the most part, the islanders were left to their own devices.

2006: Drunk poachers stray too close

Soon after Pandit’s successful visit, the Indian government began enforcing an exclusion zone around the island, with heavy fines and jail time to act as deterrents. Despite this, two poachers entered the exclusion zone in 2006 to hunt for mud crabs. As night came, they dropped their anchor some distance from the island and started to drink heavily.

Sometime during the night, the anchor became unstuck. As the men slept, their boat drifted into the coral reefs surrounding the island. They were immediately killed by the Sentinelese the next morning, who buried their bodies into the beach. When a helicopter came to retrieve their bodies, the islanders drove it off with a volley of arrows.

The Indian government’s official position is that the islanders are a sovereign people with the right to defend their borders. The Sentinelese would not be prosecuted for killing the poachers. To arrest and prosecute a Sentinelese tribesman would be clearly absurd anyhow.

2018: An American missionary dies

In November 2018, an American Evangelical missionary named John Allen Chau was killed by the Sentinelese during a protracted attempt to convert them to Christianity. In his journal, Chau wrote that North Sentinel Island was “Satan’s last stronghold,” and that, while others might think he’s “crazy” for attempting to make contact, he thought it was “worth it to declare Jesus to these people.”

“Please do not be angry at them or at God if I get killed,” he wrote.

Today, aircraft and satellites continue to keep an eye on the island, occasionally checking in to confirm the tribe’s continued existence after major storms. While curiosity about the tribe remains strong, curiosity appears to be the only real reason left to make contact. In the face of the Sentinelese’s clear preference for isolation, violating that isolation in the name of curiosity alone seems selfish.

This article was originally published on Big Think in September 2018. It was updated in August 2022.