Psilocybin ‘markedly’ boosts feelings of self-transcendence during meditation

- During a mindfulness retreat, participants that tried psilocybin reported having a richer cognitive and emotional experience.

- The effects of psilocybin were prominent even four months after the retreat.

- The combination of psychedelics and meditation is a field that’s ripe for study in therapeutic settings.

In his classic work on psychedelics, The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley writes that through hypnosis or meditation he “might so change my ordinary consciousness as to be able to know, from the inside, what the visionary, the medium, even the mystic were talking about.” Yet it was psychedelics — in his case, mescaline — that would not only get him there fastest, but also ensure that he got where he needed to go.

There has long been an argument about getting “there,” whether by natural means (meditation, breathing techniques, yoga) or via psychedelics — a debate that reached a fever pitch during Timothy Leary’s heyday and never completely went away. Fans of psychedelics profess that they offer the quickest and most encompassing route. That point is hard to argue against for anyone that’s dabbled.

One question we don’t often hear, however: What about both?

On a related note, where exactly is “there”?

A team in Germany set out to address the first question, which naturally led to speculation on the second. In a new study, published in Nature Scientific Reports on October 24, researchers from the University Hospital of Psychiatry Zürich gave 40 mindfulness meditation retreat participants either one dose of psilocybin, the hallucinogenic ingredient in a variety of mushrooms, or a placebo.

First author, Lukasz Smigielski, sums up the findings:

“Psilocybin markedly increased the incidence and intensity of self-transcendence virtually without inducing any anxiety compared to participants who received the placebo.”

Self-transcendence has long been the central focus of both meditation and the psychedelic ritual. Yet, as the authors note in the abstract, personal change is another desired effect. This bodes well for psilocybin; in therapeutic settings, it has been shown to help combat addiction, depression, and anxiety, as well as allow those in hospice care to feel content.

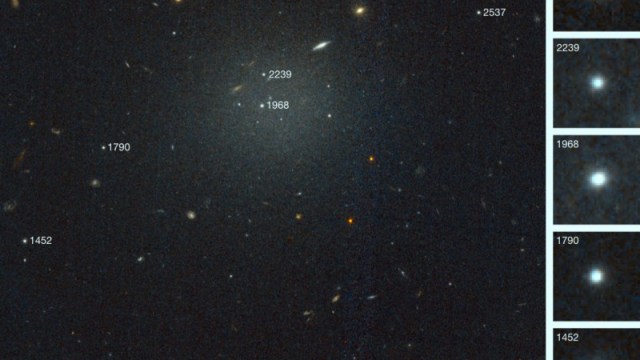

Roland Griffiths Compares Psilocybin and Meditation fMRI

Transcending the self need not be an under the Bodhi Tree experience. Not feeling anxious every day of their lives is of even greater value for many seekers. In fact, transcendence, while often invoked as a lofty, otherworldly state, can be more effectively applied to loosening the grip of lifelong anxiety. The feeling of calm that ensues is the transformation (or at least points to where it lies, which is why meditation is a good addition to the ritual).

A regular mindfulness practice has shown measurable results in coping with many of the problems above. Interestingly, there is speculation that psychedelics “reset” neural networks, leading to more sustainable long-term effects without the need of daily ingestion (though microdosing might confer benefits as well). Regardless, a discussion about how both meditation and psychedelics might help alleviate tension and depression is long overdue.

For the psilocybin group on the five-day meditation retreat, participants reported experiencing more profound states of self-dissolution without any accompanying anxiety. They also felt higher levels of openness and optimism and were better able to appraise their emotional responses. The group ingesting psilocybin not only experienced these higher levels of positive affect during the retreat, but four months later as well.

“Compared with placebo, psilocybin enhanced post-intervention mindfulness and produced larger positive changes in psychosocial functioning at a 4-month follow-up, which were corroborated by external ratings, and associated with magnitude of acute self-dissolution experience.”

Meditation, the team continues, appears to enhance the positive effects of psilocybin. They believe such studies will help guide the burgeoning filed of psychedelic-assisted therapy. As Ronan Levy, co-founder of FieldTrip, the organization behind the world’s first psilocybin research center, recently told me, current psychotherapy models were developed in the ’50s and ’60s. It might behoove mindfulness facilitators to team up with licensed psychiatrists to investigate the power of this new model.

Mazatec psilocybin mushrooms during their 3 day drying time after harvest May 14, 2019 in Denver, Colorado.

Photo credit: Joe Amon / MediaNews Group / The Denver Post via Getty Images

Anecdotally, I can recall three sublime experiences utilizing this exact combination: one seated in Voorhees Mall at Rutgers University; another beside a lake while hiking in Ramapo, NJ; finally, at the peak of Anthony Wayne Mountain, part of Harriman State Park. Each time, the combination of psilocybin and meditation left profound imprints on my consciousness — so much so, I can recall these times vividly years (and even decades) later.

What I remember most from each experience is the sensation of contentment. Huxley writes that man’s condition is discontent. Religion is a response to our existential dilemma, born of this planet as transient beings. Biology guarantees our shelf life, yet somehow we’ve tricked ourselves into believing otherwise. Psychedelics don’t promise eternal life. They remind us of the fleeting nature of everything. Instead of rebelling against basic science, they help us feel okay with that situation.

Anxiety, depression, addiction, markers of the aggrieved, as if impermanence is an offense. Mindfulness, an attempt to curb superfluous “mind stuff” through acute attention to the moment, is a powerful means for overcoming disquieting thoughts. It makes for a natural bedfellow with psilocybin, that magical group of mushrooms that intensely focus our awareness on our immediate environment, both internal and external. We return from the trip relaxed and informed, transformed, a brief but powerful respite from the incessant stream of negative thoughts that tend to arise.

Is more research needed? Of course it is. The time has come to study this fascinating combination of practices, both ancient rituals designed to help us get to know ourselves and the world better. It provides, as Blake knew — and Huxley redefined — to see everything “as it is,” not how we believe it should be. That’s some powerful therapy.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.