MDMA and Psilocybin: The Future of Anxiety Medication?

When my wife texted me from the other side of the apartment last Thursday I knew things could not be good. Four simple words: Chris Cornell is dead. While I haven’t remained up on Soundgarden or Cornell’s solo career over the last two decades, Badmotorfinger and Superunknown, along with the Temple of the Dog record, were essential high school and college listening, memories for life.

Of course you want to know what happened at such times. The NY Times initially reported potential suicide, a claim quickly verified around the web. Impatient animals we are, song lyrics and life episodes were immediately dissected for clues, including the fact that the last song Soundgarden performed was a cover of Led Zeppelin’s “In My Time of Dying.” All so poetic, this story wrapped up with the perfect bow of rock star misery.

Or is it? Cornell’s family rebutted that his medication is to blame. He might have taken a higher dosage of Ativan than usual, an anti-anxiety drug also prescribed for insomnia. Side effects include suicidal thoughts, mood swings, confusion, hallucinations, feeling unsteady, and memory problems. Cornell’s wife noticed that he was slurring his words earlier that evening.

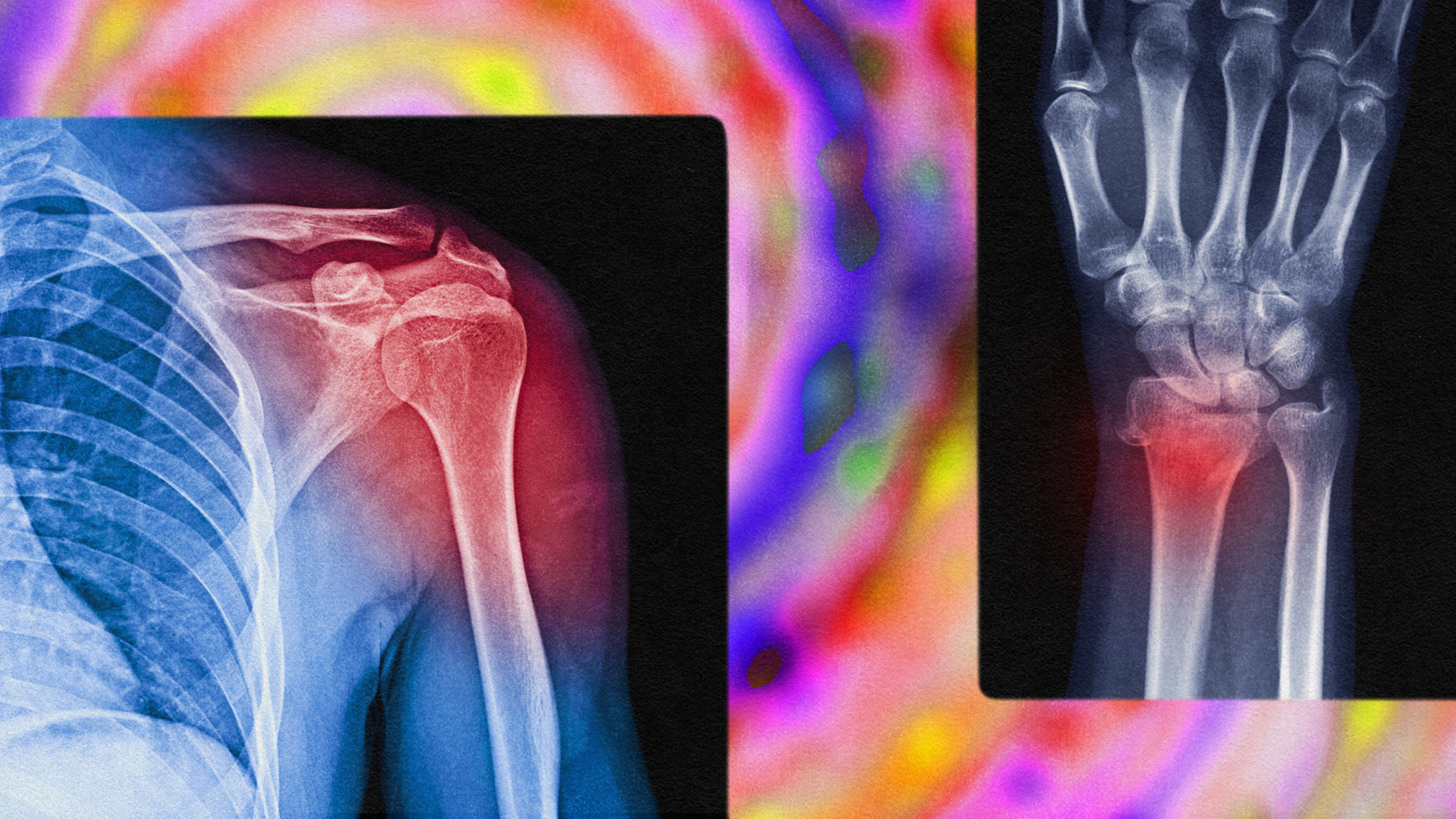

While we’ve gotten better at solving hardware problems—torn meniscuses, faulty heart valves, various cancers—we’re still working with an ancient operating system when it comes to our software. One of the failures of modern medicine is its inability to treat emotional pain, writes neuroscientist Marc Lewis and addiction specialist Shaun Shelly:

Modern medicine has confirmed the overlap of bodily and mental maladies through painstaking research, and yet treatment for psychological problems lags far behind a cascade of stunning advances in the treatment of physical ills – advances that have doubled the human lifespan and improved our quality of life immeasurably.

We’ve put a lot of faith—too much, Lewis and Shelly argue—on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which work by—well, no one is exactly sure, which is a big part of the problem. If you’re suffering from mild or moderate anxiety or depression side effects likely outweigh benefits. And yet in numerous countries they are the most commonly prescribed group of pharmaceuticals for treating emotional distress. One JAMA report stated that 16.7 percent of American adults filled at least one psychiatric drug prescription in 2013.

Given all those drugs things are not getting better. Atlantic editor Scott Stossel, who has suffered from severe anxiety for decades, writes,

These massive rates of SSRI consumption have not caused rates of self-reported anxiety and depression to go down—an in fact all this pill popping seems to correlate with substantially higher rates of anxiety and depression.

Most of these drugs do not have better efficacy rates than the placebo response. If placebo is an effective mechanism without crippling side effects then alternate means should be considered. (My chronic panic attacks, for example, were cured from a change in diet; SSRIs seemed to work sometimes, though not others.)

Lewis and Shelly entertain another solution: MDMA. Psilocybin. Natural opioids. Pharmacology that has been used in some cases for millennia to aid in emotional and existential distress is having a renaissance—a reawakening to common sense, really. As most of these potential remedies are listed as Schedule One studies are scarce, with most researchers unwilling to skirt the law to properly test their efficacy.

The idea that people become addicted to what are commonly referred to as “recreational drugs” is provably false, however. SSRIs, alongside socially sanctioned drugs like cigarettes and alcohol, are much harder to kick. You’re better off being addicted to pot or cocaine, Lewis and Shelly write, than tobacco. Furthermore, early evidence in the therapeutic applications of psychedelics is promising, making their illegality all the more troublesome:

Psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms is neither toxic (in any dose) nor addictive. For those with obsessive-compulsive disorder, psilocybin is shown to reduce symptoms significantly. Studies have catalogued the relief of end-of-life anxieties, alcoholism and depression with psilocybin. But doctors cannot prescribe it.

MDMA, they continue, reduces your amygdala’s threat response system, making you less likely to become overstimulated to benign or neutral stimulation, a marker of anxiety attacks. Research on its efficacy in reducing depression and PTSD is also promising. The problem, the authors argue, is that perception of these substances is skewed. Affiliations such as “party drugs” and images of stoners and slackers remain part of the common lore. What these drugs—and the notion of emotional fitness in general—need is a cultural reframing:

We’d rather stick to antidepressants of minimal therapeutic impact, not because they guard against addiction – they don’t – but because of a puritanical aversion to supplying unearned happiness and, along with it, a deep-seated belief that people who suffer emotionally should just get over it.

“Just get over it” is advice I heard often when suffering from hundreds of panic attacks; often only fellow anxiety sufferers offer empathy. But pulling yourself up by your bootstraps is not appropriate medicine for the physiological assault on your nervous system nor for the somatic consequences of depression. Therapy needs to be embodied; mind and body must be treated simultaneously.

Our short experiment with SSRIs, though helpful to some, has proven to be too dependent on chance and risk to be effective globally. Corporate interests will continue to dominate medicine for the foreseeable future, which is a shame when not only people’s lives but their day-to-day well-being is in play. An anxious or depressed life is not a life well-lived. We need to entertain all possibilities, especially where research is promising.

—

Derek’s next book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health, will be published on 7/17 by Carrel/Skyhorse Publishing. He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.