What is modern art about — and why won’t it go away already?

- Modernism has lasted longer than any art movement since the Renaissance.

- To understand the enduring popularity of modern art, one must first understand what this elusive movement is really about.

- The principles of modern art, though as fashionable as ever, are increasingly at odds with the present.

In his article “What the Hell was Modernism?” — soon to be released in a collection titled Art is Life — the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Jerry Saltz makes an interesting observation: Ever since the 14th century, not a single art movement has lasted longer than one or two generations.

A quick historical survey confirms as much. Leonardo da Vinci had hardly been dead for a year before the High Renaissance gave way to Mannerism, a movement that emphasized the thoughts and feelings of individual artists over the methodical representation of their subjects. In a similar manner, masculine Neoclassicism pushed aside the more feminine Rococo style, which itself had rendered obsolete the work of Baroque painters.

Modernism regards itself as the logical conclusion of art history.

The lifespan of art movements appears to have decreased over time, possibly because their development corresponds with the exponential growth of civilization. Whereas Romanticism and Realism stayed in vogue for about 50 years each, Fauvism — which made its debut at the start of the 20th century — lasted a mere five years before the arrival of Expressionism. Expressionism, in the meantime, was around for two years before Cubism and Futurism joined the party.

The sole exception to and disrupter of this trend is Modernism. The art movement, introduced to Americans over a century ago, is still fashionable today. As Saltz points out, many of the world’s leading museums, from the Museum of Modern Art to the Guggenheim, are devoted exclusively to modern art. “Kids,” he adds, “sport tattoos of artwork by Gustav Klimt, Henri Matisse, Salvador Dalí, Edvard Munch, Piet Mondrian, and Andy Warhol,” and “our cities are crowded with glass-walled luxury riffs on high-Modernist architecture, the apartments inside full of knockoffs of ‘mid-century modern’ furniture.”

All this begs the question: Why has modern art survived while other art movements have not?

What is modern art anyway?

In order to understand why Modernism is still around today, you first have to understand what it is about. This is easier said than done, as the movement does not easily lend itself to categorization and description. “It is disastrous to name ourselves,” exclaimed the artist Willem de Kooning, a remark that helps explain why the differences between his work and, say, the work of Piet Mondrian are so much starker than Rafael and Michelangelo.

In fact, modern art is so elusive that historians can’t agree on when it began. Some of them refer to Édouard Manet as the first Modernist painter. Others settle for Paul Cézanne, specifically his painting The Bathers. Others still trace the birth of Modernism back to Francisco Goya, who lived several centuries before the previous two were born.

One thing that connects these very different artists is their mutual disregard for convention. Manet, Cézanne, and Goya all painted in styles that were nothing like their contemporaries. They used broad brush strokes, flat plains of colors, and manipulated perspectives to construct scenes that were at once simplified and intensified.

For some giants of Modernism, disregard bordered on disgust. Marcel Duchamp famously said he wanted to use a Rembrandt as an ironing board. While the aforementioned painters were concerned with discovering new forms of expression, Duchamp wanted to question the definition of art itself. To that end Duchamp, who once said that “a painting that doesn’t shock isn’t worth painting,” submitted an ordinary urinal signed “R. Mutt” to a 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists.

Many artists have tried to rival the controversy that ensued at the Society when the urinal was unveiled; in 2019, the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan came close when he stuck a banana to a wall with duct tape.

The endpoint of art

Aside from being rebellious and indeterminate, modern art also aspires to be truthful. “These radical artists are right,” the critic Harriet Monroe wrote as early as 1913. “They represent a search for new beauty… a longing for new versions of truth observed.”

What Monroe means is that, through abstraction, modern art is able to reveal things about life, existence, and reality that previous art movements — enslaved as they were to their own subjects — could not. To paraphrase many a modern manifesto, narrative and representation are distilled into their simplest, purest, truest forms: color and composition. Subjectivity, in other words, is replaced by objectivity.

This brings us to the last and arguably most important characteristic of Modernism: its tendency to regard itself as the logical conclusion of art history. Modern artists envisioned this history as a straight line that stretched from prehistoric cave art all the way to the present — that is, a point in time when painting had been abstracted so many times already that it could not possibly be abstracted further.

Numerous 20th century artists claimed that they were the ones to reach the singularity. Ad Reinhardt, working on his monochromatic grid paintings, said he was “merely making the last painting which anyone can make.” Clearly this couldn’t have been the case, as Soviet artist Alexander Rodchenko had “reduced painting to its logical conclusion” and “affirmed it’s all over” before Reinhardt did, and Duchamp had declared painting dead when Rodchenko was still in school.

Beyond Modernism

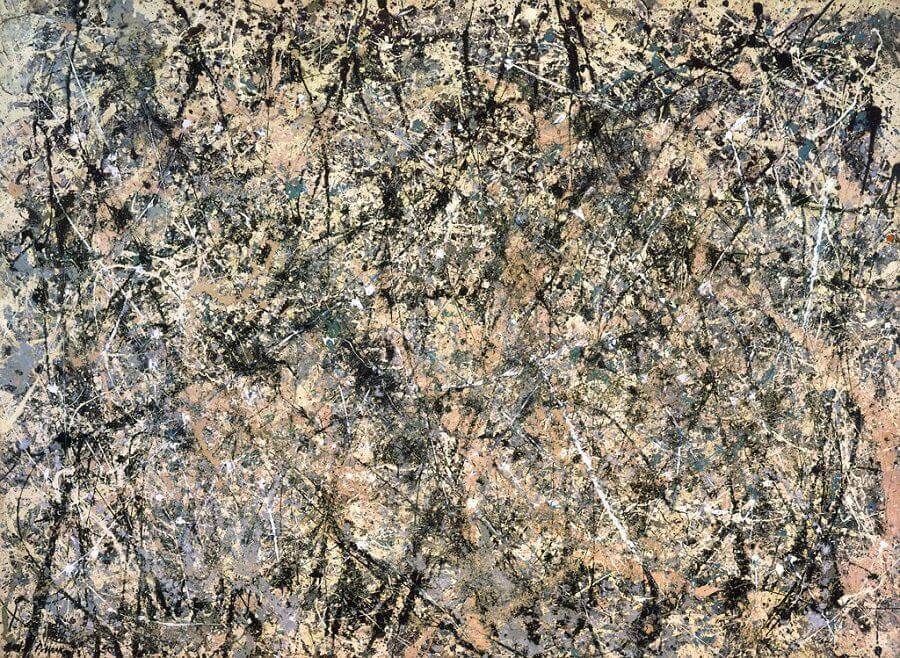

The characteristics of modern art help explain its enduring popularity. Because the movement is a denunciation of everything that came before, viewers do not require a working knowledge of art history – or history in general – to appreciate it. Whereas the beauty and genius of the Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini is contingent on one’s familiarity with scriptures, myths, and the predicament of the Roman Catholic Church after the Protestant Reformation, a painting by Jackson Pollock, the critics maintain, has to be experienced rather than analyzed, felt rather than understood.

Another curious feature about Modernism is that people are as interested in the art as they are in the artists themselves. Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, and Andy Warhol were not only treated as geniuses but also as celebrities, sex symbols, and style icons. We also remember them as underdogs and iconoclasts who, despite being doubted and ridiculed at the start of their careers, eventually ended up on top.

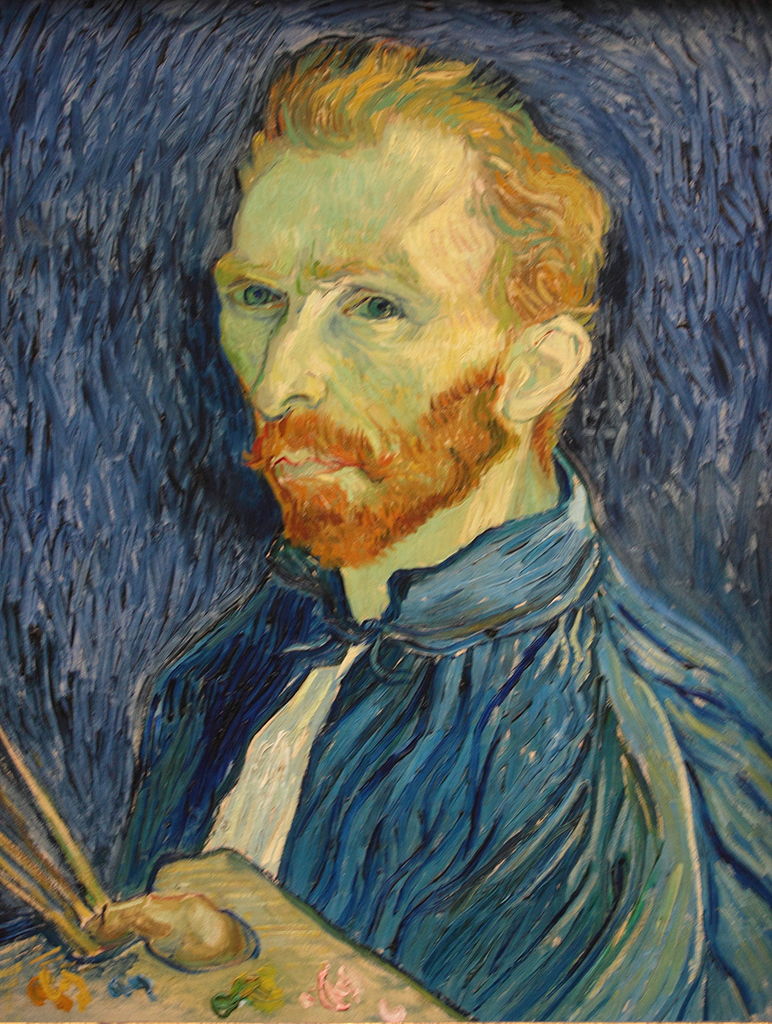

That goes double for artists who died before their big break, like Vincent van Gogh. “Adolescents,” writes Saltz, “feel big feelings because the world did not understand Vincent.” As a result, his art has become all but inseparable from his tragic life, with the latter serving as the lens through which to look at the former. The same cannot be said about fellow Dutchman Johannes Vermeer who, although he died in poverty and anonymity just like van Gogh did, is mostly remembered for his art and not his person.

The title of Saltz’s article, “What the Hell was Modernism?” suggests the movement has finally dissipated. However, this is not necessarily the case, as Postmodernism — the art movement we are witnessing today — is virtually indistinguishable from its predecessor. The very name “Postmodernism” indicates it is defined by its relationship to modern art. Several overlapping qualities, including experimentation and what Saltz terms the “fetishizing of novelty,” add to the confusion.

That’s not to say the two are completely inseparable, though. Just as Modernism rejects old art movements, so too does Postmodernism turn its back on Modernism and its underlying ideas. Where Modernism held an unwavering faith in progress, Postmodernism has a suspicious and skeptical nature. It regards the notion that art history is linear as highly contentious, not in the least because the individuals who promoted this argument were overwhelmingly white and male.

Instead of looking to create the final paintings of mankind, Postmodern artists seek to critique overarching narratives, express their individuality, and empower voices that have been ignored or suppressed. Where modern art was elitist, enigmatic, and always resting on the shoulders of giants, Postmodernism is open, inviting, and collaborative.

While still as fashionable as ever, the founding principles of modern art are increasingly at odds with today’s political and cultural climate. In that sense, this supposedly immortal movement has at long last been relegated to the place it wanted to escape: the past.