Money isn’t a thing, it’s a philosophy. The ancient Greeks were the first to realize it.

- Although the Greeks did not invent coins, they were among the first to use coins as “money” in the contemporary sense of the word.

- During the Classical period, coins were the only acceptable forms of payment as well as a measurement capable of expressing the relative value of all things.

- Coins not only enabled the development of city-states and their political economies, but also left their mark on philosophical discourse.

It’s hard to imagine life without the concept of money. But for most of human history, there was no money, in the modern sense of the word. For a better look into the role money plays in our world today, let’s turn back the clock to the dawn of money.

The oldest written references to daily life in ancient Greece can be found in the epics of Homer, namely in the Iliad and the Odyssey. Though these texts are works of mythology, Hellenistic scholars have long looked to them for clues about everyday life in ancient Greece.

The epics indicate that the Homeric age, which lasted from 1200 to around 800 B.C., was an age without money. Homer expresses the value of objects not in terms of coins, but cattle. Each of the gold tassels of Athena’s aegis, for instance, is described in the Iliad as being worth 100 oxen. The German economic historian Bernard Laum traces the economic significance of cattle back to sacrificial practices.

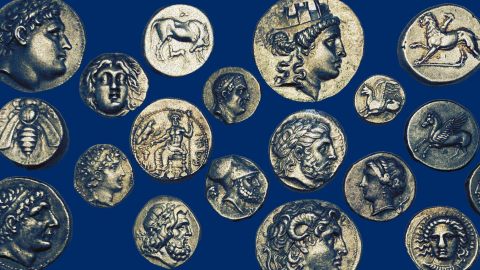

In the subsequent Classical period, trade looked much different. Instead of oxen, the citizens of Greece’s city-states made their purchases using coins made from valuable materials and validated with official seals. As currency, coins were far more practical than farm animals, so practical, in fact, that they fueled the creation of entirely new industries and even facilitated the rise (and fall) of several ancient superpowers, notably Athens.

Although the Greeks might not have been the first civilization in history to carry around coins, they were among the first to use those coins as “money” in the modern sense of the word: a medium of exchange that’s durable, portable and uniformly accepted.

More than means of commerce, Greek coins were social constructs that drastically altered the way people looked at — and interacted with — reality, reshaping the business, politics and even philosophy of ancient Greece.

Coins enter the Greek world

Some of the earliest known coins were found in Lydia, an Iron Age kingdom located in Asia Minor between the Greek islands and the Persian Empire. The coins date back to 625 and 600 B.C. and were made from electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold, silver, copper and other metals. Known as “white gold” to the Greeks, electrum was plentiful, valuable and durable — qualities which made the material a perfect source for coin-making.

Why these coins came into being is unclear. Some archeologists speculate that the Lydians had invented them for their own use. Others believe they were produced to pay Greek mercenaries. This view is supported by the fact that the smallest Lydian coins were worth the equivalent of a day’s work and unsuitable for small payments like a loaf of bread. It would also explain how the invention eventually found its way to Greece.

The earliest known Greek coins were traced to Aegina, an island off the coast of Athens. They are dated to 600 B.C., suggesting that the Lydian invention spread quickly. Like their Lydian counterparts, coins from Aegina were initially made from electrum, and too valuable to have been of use for everyday transactions. Greek coins typically carried the symbol of the place they were produced; those from Aegina were brandished with the image of a sea turtle.

In his aptly-named book Archaic and Classical Greek Coins, the eminent numismatist Colin M. Kraay discusses various purposes for coins, including the collection of harbor dues, fines and taxes. The observant reader will notice a trend: Before coins were used for trade between citizens, they were used to make payments to the state.

Turning coins into money

Even though the Greeks did not invent coins, they did invent money as we know it today. This, at least, is the central argument of The Invention of Coinage and the Monetization of Ancient Greece by the classical studies professor David Schaps. Schaps says that for money to be considered money, it must be exclusively acceptable. This was not true for the ancient Near East, where cattle and grain functioned as payment alongside minted coins.

Once coins were introduced in Greek city-states, they quickly became the only viable form of payment. Unlike the so-called “primitive money” that was being used in Asia Minor, Greek coins were also worth more than their intrinsic value. For us, a society that uses fiat money made from paper, this is nothing special. However, in classical antiquity, this was no small feat, as any such surplus value was based solely on the power of and trust in state institutions.

Last but not least, ancient Greek coins acquired a semantic significance that primitive money never possessed. The Greeks were keenly aware that money allowed them to express everything in terms of a single, standard unit, redrawing the relationship between objects.

According to Schaps, it should come as no surprise that our current conception of money evolved inside the Greek polis, an environment which — despite its ancient particularities — closely resembles the modern city.

“It was Greece that was searching for new forms of government,” Schaps writes, “and coins made that administration and that organization simpler and more manageable than [primitive money] could have done.”

Coinage and daily life in ancient Greece

The invention of money revolutionized life in ancient Greece. Coins made it easier to pay wages as well as take out loans, enabling entrepreneurship and giving rise to new professions like money changers and sophists: philosophers who offered their oratorical expertise in exchange for cash. The ancient world became more connected than ever before, as coinage stimulated trade between Greek city-states and abroad.

As indicated by Schaps, the evolution of ancient Greek coinage is closely correlated with the development of the city-state. Archeological evidence suggests that coins were first adopted to provide governments with regulated and reliable sources of income, with the state occupying the same position in the economy that banks do today. This idea is supported by the fact that, throughout Greece, coin-making was a public rather than private enterprise.

The topic of coinage is even addressed in Greece’s best-known philosophical discourse. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle uses coins to illustrate the distinction between the natural and the artificial. The philosopher recognizes coins as a “mere sham,” stating that “it is within our power to alter and to make it useless.” At the same time, he recognizes coins as tools that allow us to more easily organize a society with the goal of achieving justice and harmony.