Why the paradoxes of infinity still puzzle us today

- Thoughts of the infinite have mesmerized and confounded human beings through the millennia.

- The concept of infinity remains a controversial and paradoxical topic today, galvanizing international conferences and heated scholarly disputes.

- In his book Probable Impossibilities: Musings on Beginnings and Endings, Alan Lightman explores the history of the concept of infinity and how it’s been contemplated by thinkers across various disciplines.

Excerpted from Probable Impossibilities: Musings on Beginnings and Endings, written by Alan Lightman and published by Vintage Books.

The Man Who Knows Infinity

In Jorge Luis Borges’s story The Book of Sand, a mysterious stranger knocks on the door of the narrator and offers to sell him a Bible he came by in a small village in India. The book shows the wear of many hands. The stranger says that the illiterate peasant who gave him the book called it the Book of Sand, “because neither sand nor this book has a beginning or an end.” Opening the volume, the narrator finds that its pages are rumpled and badly set, with an unpredictable Arabic numeral in the upper corner of each page. The stranger suggests that the narrator try to find the first page. It is impossible.

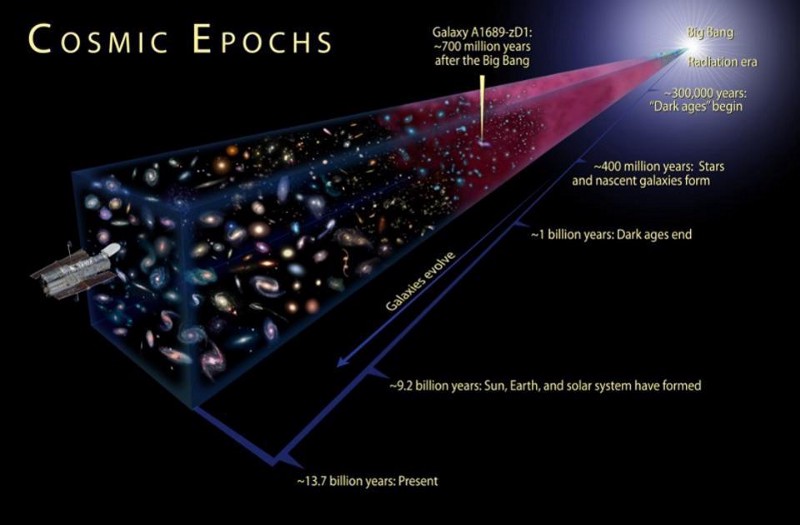

No matter how close to the beginning he explores, several pages always remain between the cover and his hand. “It was as though they grew from the very book.” The stranger then asks the narrator to find the end of the book. Again, he fails. “It can’t be,” says the narrator. “It can’t be, but it is,” says the Bible peddler. “The number of pages in this book is literally infinite. No page is the first page; no page is the last.” The stranger pauses and reflects. “If space is infinite, we are anywhere, at any point in space. If time is infinite, we are at any point in time.” (Note to the observant reader: We cannot be at any point in time. Life can exist only during a relatively short period of cosmic history, as discussed in the last chapter.)

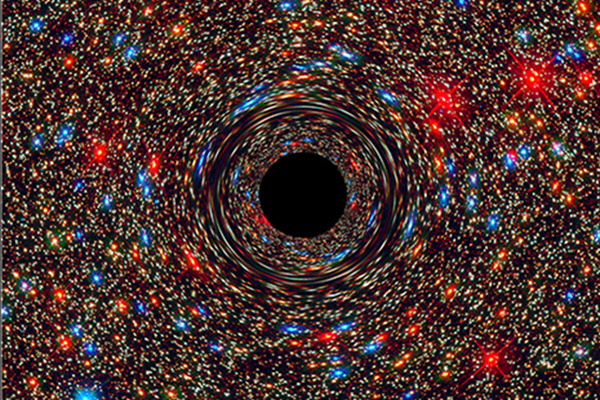

Thoughts of the infinite have mesmerized and confounded human beings through the millennia. For mathematicians, infinity is an intellectual playground, where an endless string of fractions can add up to 1. For astronomers, the question is whether outer space goes on and on and on and on ad infinitum. And if it does, as cosmologists now believe, unsettling consequences abound. For one, there should be an infinite number of copies of each of us somewhere out there in the cosmos. Because even a situation of minuscule probability—like the creation of a particular individual’s exact arrangement of atoms—when multiplied by an infinite number of trials, repeats itself an infinite number of times. Infinity multiplied by any number (except 0) equals infinity.

Measurements of infinity are impossible, or at least impossible according to the usual notions of size. If you cut infinity in half, each half is still infinite. If a weary traveler arrives at a fully occupied hotel of infinite size, no problem. You simply move the guest in room 1 into room 2, the guest in room 2 into room 3, and so on ad infinitum. In the process, you’ve accommodated all of the previous guests and freed up

room 1 for the new arrival. There’s always room at the infinity hotel. We can play games with infinity, but we cannot visualize infinity. By contrast, we can visualize flying horses. We’ve seen horses, and we’ve seen birds, so we can mentally implant wings on a horse and send it aloft. Not so with infinity. The unvisualizability of infinity is part of its mystique.

The first recorded conception of infinity seems to have occurred around 600 BC and is attributed to the Greek philosopher Anaximander, who used the word apeiron, meaning “unbounded” or “limitless.” For Anaximander, the Earth and the heavens and all material things were caused by the infinite, although infinity itself was not a material substance. Other ancient Greek philosophers held that infinity was a negative, even an evil, because the inability to measure a thing was considered a shortcoming of the thing—with the exception of the infinite and immeasurable One. About the same time as

Anaximander, the Chinese employed the word wuji, meaning “boundless,” and wuqiong, meaning “endless,” and believed that the infinite was very close to nothingness. (An interesting perspective on Pascal’s ideas, discussed in “Between Nothingness and Infinity.”) In Chinese thought, being and nonbeing, like yin and yang, are in harmony with each other—thus the kinship of infinity and nothingness.

A few centuries later, Aristotle argued that infinity does not actually exist. He conceded something he called potential infinity, such as the whole numbers. For any number, you can always create a bigger number by adding one to it. This process can continue as long as your stamina holds out, but you can never get to infinity. Indeed, one of the many intriguing properties of infinity is that you can’t get there from here. Infinity is not simply more and more of the finite. It seems to be of a completely different nature, although pieces of it may appear finite, like large numbers, or like large volumes of space. Infinity is a thing unto itself. All we see and experience has limits, boundaries, tangibilities. Not so with infinity. For similar reasons, St. Augustine, Spinoza, and other theological thinkers have associated infinity with God: the unlimited power of God, the unlimited knowledge of God, the unboundedness of God. “God is everywhere, and in all things, inasmuch as He is boundless and infinite,” said St. Thomas Aquinas.

Beyond the religious sphere of the immaterial world, physicists believe that there may be infinite things in the material world as well. But this belief can never be proven. You can’t get there from here. Most of us have our first glimmerings of infinity as children, when we look up at the night sky for the first time. Or when we go to sea, out of sight of land, and gaze upon the ocean extending on and on until it meets the horizon. But these are only glimmerings, like counting to a few thousand in Aristotle’s potential infinity. We’re overwhelmed. But we haven’t come close.

The concept of infinity remains a controversial and paradoxical topic today, galvanizing international conferences and heated scholarly disputes. Can physical forces ever be infinite in strength? Can physical space extend beyond galaxy after galaxy without limit? Is there an infinity between the infinity of the whole numbers and the infinity of all numbers? In May 2013, a panel of scientists and mathematicians gathered in New York City to discuss the profound conundrums surrounding infinity. William Hugh Woodin, a mathematician at the University of California, Berkeley, put it this way: “It’s kind of like mathematics lives on a stable island—we’ve built a solid foundation. Then, there’s the wild land out there. That’s infinity.”