What 11 emerging countries think about increased diversity

A glance at news headlines could lead one to believe our world has lost to tribalism and hate. In just the last few years, we’ve seen white supremacists march openly in American streets, extremist forces target cultural sites serving as reminders of humanity’s shared heritage, places of worship terrorized, minorities blamed and assaulted over myths about novel coronavirus‘s origins, and leaders propose a myriad of attempts to reject refugees and migrants.

This is a part of today’s reality, but it’s worth remembering that news headlines aren’t a trend analysis. They are a collection of reports and instances that tell only one side of our story—often the scariest and most extreme part.

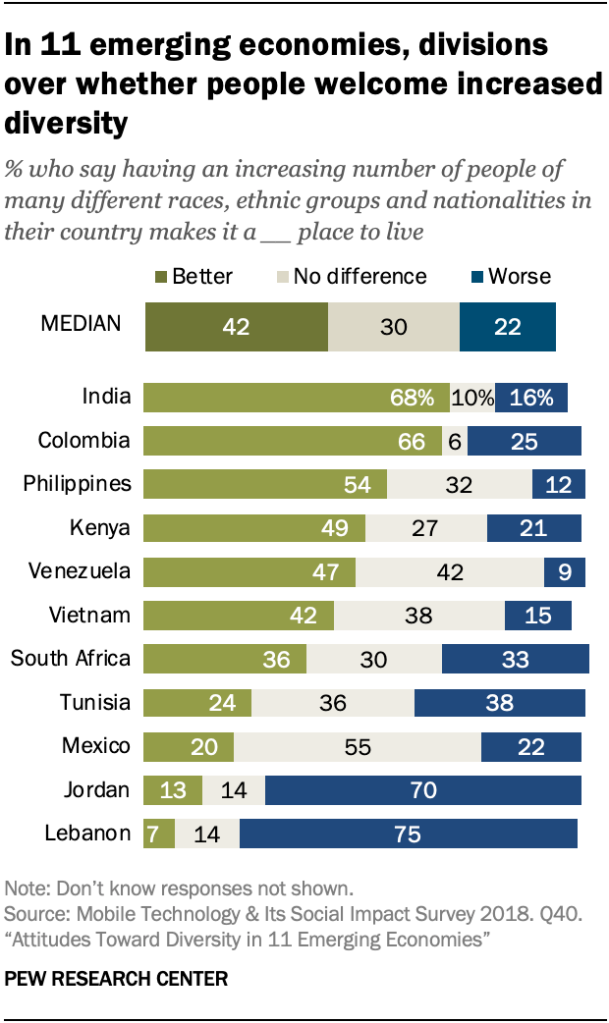

Far from being pushed to the fringes, cosmopolitanism and the ethics of diversity may be enjoying a heyday according to Pew Research Center data from 11 emerging countries.

The center surveyed more than 28,000 peoples across Columbia, India, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Mexico, Tunisia, Venezuela, Vietnam, South African, and the Philippines on their opinions of diversity within their borders. These countries were chosen based on their middle-income status, differing degrees of technology ownership, and high levels of migration (internal or external).

The survey asked respondents how they viewed increasing numbers of other races, religions, and nationalities and what effect that had on the quality of life in their countries. Additional questions were tailored to a country’s unique demographics and circumstances.

For example, respondents in the Philippines were asked how favorably they viewed Muslims and Christians, while Tunisians were asked about Sunnis and Shiites. Others, such as Mexico and Lebanon, were asked about asylum seekers fleeing to their countries.

Pew found that “[a]cross the 11 countries surveyed, more said their countries are better off thanks to the increasing number of people of different races, ethnic groups, and nationalities who live there.” A minority said the increase made no difference, and an even smaller minority said their country was worse off.

Lebanon and Jordan took in millions of Syrian refugees during the civil war, helping to explain their complex relationship with diversity in their borders.(Photo: AFP via Getty Images)

When looking at results from individual countries, the picture becomes much more nuanced. A majority of respondents from India, Columbia, the Philippines, Kenya, and Venezuela agreed with the statement that increased diversity made their countries better places to live. Conversely, a minority agreed with the same statement in Tunisia, Mexico, Jordan, and Lebanon.

The reasons for these divergences seem to stem not only from deep historical divides but also current events. Lebanon, which held the most negative views of diversity among the eleven, took in an estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees, a massive influx for a country of around 7 million. Jordan too saw a massive wave of asylum seekers from the civil war; likewise, its respondents held that increasing numbers of different peoples made life in their country worse.

Mexico has also seen a surge of asylum seekers from Central American countries, yet its overall view wasn’t as unfavorable as either Jordan or Lebanon. However, it was the only country in the set to have a majority hold that increasing ethnic and religious diversity made no difference to the quality of life. And about half those surveyed did hold negative views toward refugees.

But while current unrest in some regions has strained relations, it’s not the whole story that refugees and migrants generate negativity toward others. Views differ widely.

Kenya, for example, maintains large refugee camps housing asylum seekers from Somalia and South Sudan, yet half of the country’s respondents believed this multicultural status improved life in their country. And a majority held approving opinions of refugees.

Similarly, about half of respondents from Venezuela, Vietnam, and Jordan rated migrant and refugee groups favorably. Yes, Jordan.

Though a majority of Jordanians believe increasingly diverse peoples make their country worse, they nonetheless hold agreeable views of refugees. The researchers speculate this divergence may stem from the fact that Jordan hosts two large refugee groups—recent Syrian refugees and Palestinian refugees who have been in the country since the conflicts of the mid-20th century. They found that Jordanians who self-identified as Palestinians viewed refugees more favorably.

Why diversity and inclusion aren’t about race but everyone thinks they are | Michael Bushwww.youtube.com

So, what leads to improved views of multiculturalism? According to Pew’s data, those with the most positive views on racial, ethnic, and religious diversity were those who interacted most with these groups. More contact equaled more positive views.

In all of the countries, younger adults were more likely to interact with people of different backgrounds, and except for Jordan, they also held more favorable views of others. The same held true for those who attained higher levels of education.

This data mirrors another Pew survey in which researchers asked Americans their views on increased racial and ethnic diversity.

Around 58 percent of Americans said increasing numbers of diverse people would make the United States a better place to live. Only 9 percent said it would make the country worse, while 31 percent said it didn’t make a difference. Opinions were split along partisan lines, with more Democrats viewing the statement favorably than Republicans.

But like the 11 emerging countries, Americans varied by age and education, too. Fifteen percent of respondents 65 and older believed growing multiculturalism made the U.S. worse—the highest of any age group. And 70 percent of college graduates saw diversity in a positive light, compared to 45 percent of those with a high school diploma or less school.

The survey’s complete results can be found here, while the survey on American attitudes on diversity is here.

These data suggest that the world hasn’t succumbed to a new era of tribalism and hate. Far from it. The beliefs of cosmopolitanism and ethics of diversity are, in fact, spreading across many of the world’s emerging countries and will likely increase as subsequent generations become more educated and integrated. That progress may be uneven, but it’s real and measurable.

An appreciation of, even desire for, diversity won’t end the tragic events that generate eye-catching headlines, but it can make our shared futures more manageable. As Kwame Anthony Apiah wrote in his book “Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers”: “I am urging that we should learn about people in other places, take an interest in their civilizations, their arguments, their errors, their achievements, not because that will bring us to agreement, but because it will help us get used to one another.”