The insult that sparked Genghis Khan to destroy an empire

- Genghis Khan invaded the Khwarazmian Empire after its sultan executed a caravan of Mongol traders.

- While sources sketch a detailed and reliable account, it’s unclear why Khwarazmia picked a fight it never could have won.

- The empire’s collapse opened the door for the Mongols to enter the Near East and Europe.

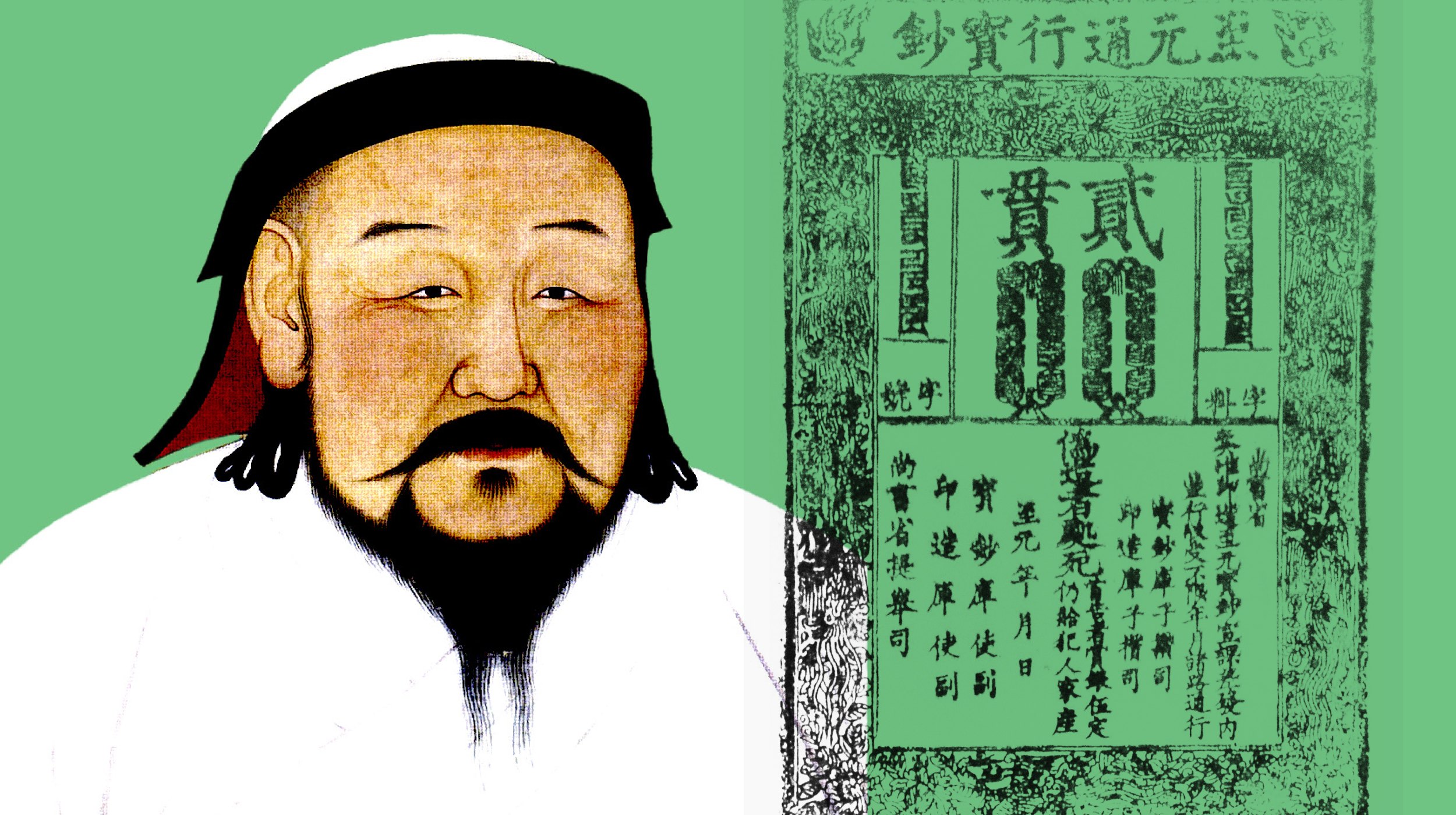

A small spark — an insult, a show of disrespect — is sometimes all it takes to ignite a war. Among the many tales of retribution echoing through history, one stands out for its scale and brutality: the tale of Genghis Khan, the Mongol leader who united the tribes of Central Asia and carved out history’s largest land empire, and his decision to wipe out the Khwarazmian Empire.

In the early 13th century, Genghis Khan sought to establish peaceful trade relations with the neighboring Khwarazmian Empire, which was a powerful Muslim state that spanned much of present-day Iran, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. The Khwarazmian Empire was ruled by Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad II.

In 1218, Genghis Khan sent a caravan of Muslim merchants to the Khwarazmian city of Otrar to engage in trade. But the governor of Otrar, Inalchuq (also known as Ghiyas ad-Din), accused the members of the caravan of being spies and ordered their arrest. Despite the protestations of their innocence, the governor had the entire caravan executed, with the exception of one survivor who managed to escape and bring news of the massacre back to Genghis Khan.

Outraged by the unjust treatment of his merchants, Genghis Khan sent a diplomatic mission to the Khwarazmian Shah, Muhammad II, to seek redress for the incident. He demanded that the governor of Otrar be punished for his actions and that reparations be made for the loss of life and property. However, the Shah not only refused to comply with Genghis Khan’s demands but also added further insult by beheading the chief envoy of the diplomatic mission and sending the head back to the Mongols.

It was a pivotal decision. The Mongols invaded the Khwarazmian Empire in 1219. Within two years, the Mongols obliterated the empire through a brutal and decisive campaign, likely killing millions of people, many of whom were women and children. To put the violence into context, the 13th-century Persian scholar Atâ-Malek Juvayni wrote that 50,000 Mongol soldiers were each ordered to kill 24 citizens of Gurganj, a city in the Khwarazmian Empire. That would amount to killing 1.2 million people, though it’s unclear whether this account was real or exaggerated.

Myth or reality?

Although there is plenty of historical evidence about this particular Mongol invasion and its brutality, it’s still hard to be sure how exactly this conflict started. After all, there are many legends and tall tales surrounding the Khan of Khans. It is also said, for example, that Genghis, born Temüjin, killed his half-brother because he wouldn’t share his food; that he turned an enemy archer who shot him in battle into one of his own generals; and that everyone who participated in his burial was killed to keep his final resting place a secret.

How accurate are any of these anecdotes? Historians aren’t always sure. Not all sources describing the history of Mongol conquest have survived, and when it comes to those that did it’s important to consider whether the authors fought with the Mongols or against them. Numerous accounts, including those detailing the life and death of Genghis himself, were produced years after the fact, making them susceptible to rumor and revisionism.

Upon closer inspection, the decimation of Khwarazmia seems to have happened, more or less, in the way it’s commonly told, with some minor differences. Still, some questions go unanswered. We do not know, for instance, why the outnumbered and outplayed Khwarazmians picked a fight with the most fearsome and accomplished conqueror alive. Perhaps they underestimated the Mongols. Perhaps they overestimated themselves. Perhaps they believed that the Mongols, who had already conquered many of Khwarazmia’s neighbors, would eventually come for them as well, and wanted to make a final stand while they still could.

The Utrar incident

According to Nicholas Morton, author of The Mongol Storm: Making and Breaking Empires in the Medieval Near East and professor at Nottingham Trent University, the stage for the Mongol invasion of Khwarazmia in 1219 was set when a caravan arrived in the city of Utrar, located in modern-day Kazakhstan, to trade with the locals. For some reason, Utrar’s governor, Inalchuq, arrested the traders and asked his superior, the Khwarazmian Sultan Ala ad-Din Muhammad II, what he should do with them.

Muhammad ordered Inalchuq to kill the Mongols, which he did. When Genghis received the news, he sent an envoy straight to Muhammad to demand an explanation. Instead of offering one, Muhammad had the envoy executed. He also humiliated his followers by cutting off their beards, symbols of masculinity and strength in Mongol culture. This time Genghis didn’t send an envoy, but an army. Utrar was besieged and Inalchuq killed by having molten metal poured into his mouth, eyes, and ears.

While the Mongols employed a number of brutal methods to punish their enemies (in Russia, they suffocated prisoners of war by burying them underneath a wooden platform and throwing a victory feast atop the platform), showering someone in piping hot metal was not a part of their typical MO, which makes you wonder why they opted to end Inalchuq in this manner. Maybe they wanted to mock his greediness. Maybe they wanted to mock the customs of his people. The Roman general Marcus Crassus is believed to have died this way at the hands of the Parthians, who occupied Afghanistan before Khwarazmia. The same goes for the Roman Emperor Valerian, who was himself taken prisoner in the region.

Once Utrar fell, the rest of Khwarazmia followed suit. While the Mongols were already feared far and wide for their cruelty, their invasion of Khwarazmia set an entirely new standard. Conservative estimates place the total death toll between 2 and 15 million people.

Some claim that Sultan Muhammad was chased across his collapsing empire until he died on a small island in the Caspian Sea while Genghis’ soldiers surrounded him, but this is only partly true. While the Sultan did take refuge at sea, Peter Jackson, author of The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion, writes in an email that the Mongols “can’t be said to have been ‘closing in’ on [him] when he died… they had missed him, in fact, and were still moving further westwards.”

Unanswered questions

Although our knowledge of the Utrar incident is founded on what Jackson refers to as “reasonably reliable primary sources,” those sources fail to explain why Muhammad and Inalchuq thought it was a good idea to antagonize the much more powerful Mongols. When the caravan arrived, Genghis already had a reputation as somebody that nobody in their right mind wants to mess with. He had conquered northern China and Zhongdu (modern-day Beijing) as recently as 1215, followed by Qara Khitai in 1218.

Considering that Qara Khitai shared its border with the Khwarazmian Empire, one would think Muhammad would be extra careful around Genghis. To a certain extent, it seems that he was. As Morton points out in the introduction to The Mongol Storm, the Sultan “had just cut short a major invasion staged in the Southwest against the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad — a decision that some speculated was driven by the rising Mongol presence in the Northeast.”

The Utrar incident is made all the more puzzling when you consider that the Mongols probably had no interest in conquering Khwarazmia prior to Muhammad’s provocations. According to Morton’s book, the trading caravan had come all the way to Utrar to exchange gold and beaver for Khwarazmian fabric — fabric that Genghis, who famously welcomed cultural and religious diversity in the regions that he occupied, had developed a taste for years earlier.

Provoking a fight with Genghis Khan

One can only guess why Muhammad saw fit to pick a fight with Genghis Khan. The Mongol Storm mentions the possibility that an Indian merchant accompanying the caravan may have insulted Inalchuq. This theory, drawn presumably from one of the primary sources, is not unthinkable, though it does not explain why the governor had the Mongol traders arrested, too, or why the Sultan insisted on having both them and the envoy executed.

Maybe it was greed that motivated the Khwarazmians, though this too is improbable. As Morton explains in an email, “Utrar was a major city on the Silk Roads and large merchant caravans were a common sight — there were almost certainly wealthier and less sensitive targets available had Inalchuq wanted to prey on the merchants passing through the city’s gates,” not to mention products more valuable and worthwhile than beaver fur.

The most convincing explanation is that Inalchuq had the Mongolian traders arrested because he thought they were spies and that Muhammad had both them and the envoy killed to send a message to Genghis Khan. The Sultan, Morton writes, may have “viewed war with the rapidly expanding Mongols as inevitable, given the rapidity of the conquests in recent years. He might therefore have chosen to act decisively at the suggestion that the Mongols were spying.”

To Morton, none of these theories is satisfactory on its own. The only thing we can be certain about is that the Mongols were moving in every direction and that, sooner or later, through war or peace, the Khwarazmians would have been forced to submit to the rule of Genghis Khan. By refusing to accept his fate, Muhammad II opened the door through which the Khan of Khans and his soldiers marched into the Near East and later Europe. But that is another story.