mind

If love is an addiction, your first love is the first dose.

When you unintentionally step on a dog’s tail, does it know that it was an accident?

What if you are the only person in the world who can think?

There’s no telling whether machine-learned common sense is five years away, or 50.

Science confirms what you already knew about being helpful to others.

▸

5 min

—

with

Our brains believe $10 today is more tangible than $100 next year.

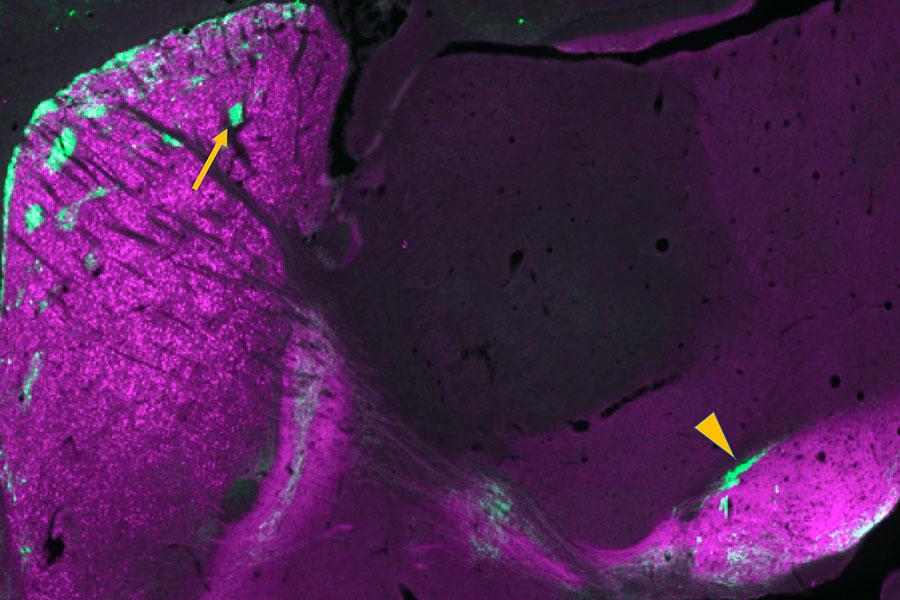

A new brain imaging study explored how different levels of the brain’s excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters are linked to math abilities.

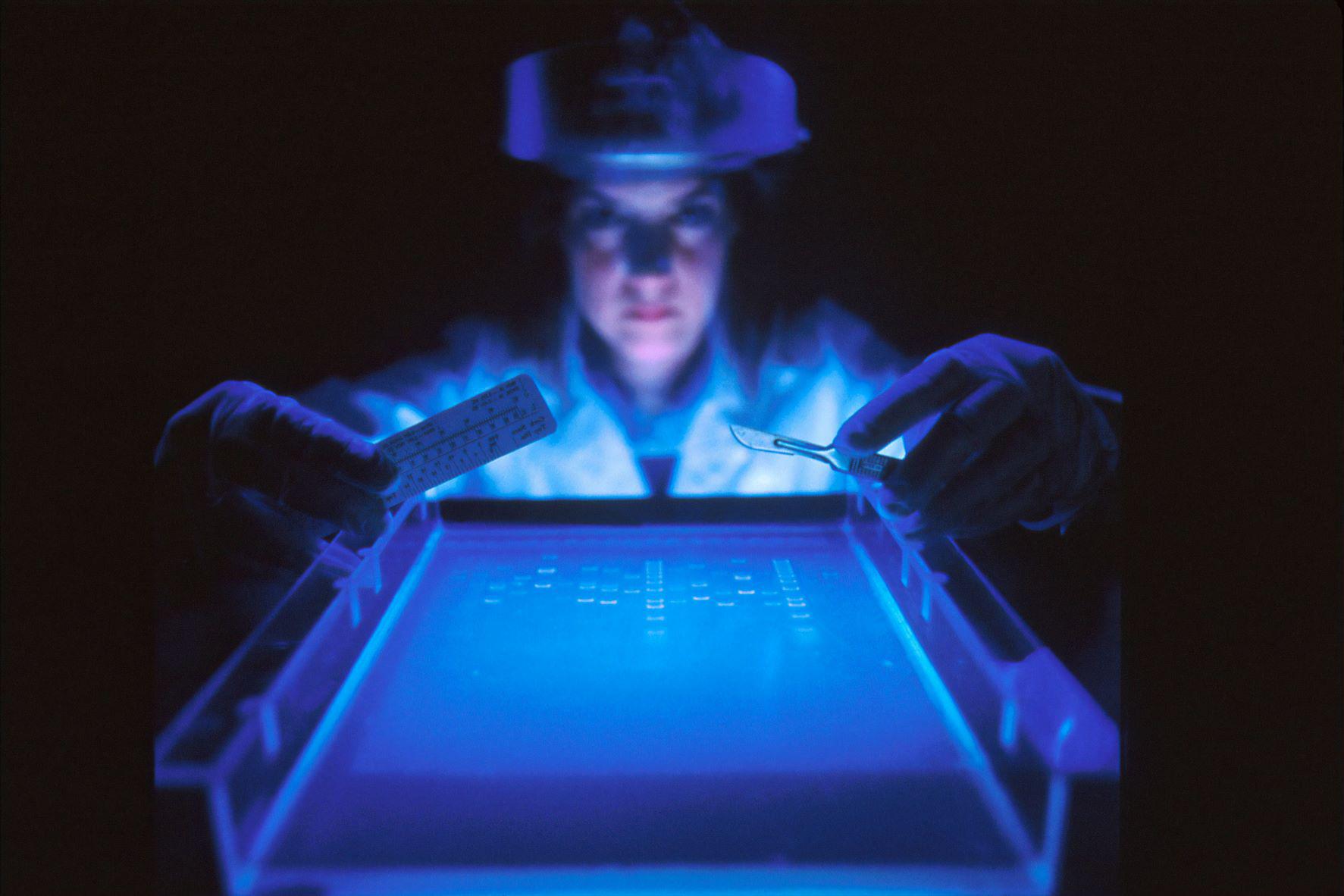

Brain cells snap strands of DNA in many more places and cell types than researchers previously thought.

A new episode of “Your Brain on Money” illuminates the strange world of consumer behavior and explores how brands can wreak havoc on our ability to make rational decisions.

Tips from neuroscience and psychology can make you an expert thinker.

People tend to reflexively assume that fun events – like vacations – will go by really quickly.

A theoretical physicist returns to Penrose and Hameroff’s theory of “quantum consciousness.”

Theoretical physicist Leonard Mlodinow offers three strategies for relaxing your cognitive filters to give your brilliant ideas time to shine in the spotlight of the conscious mind.

The evidence for a link between time spent using technology and mental health is fatally flawed.

What most people don’t realize is that everyone’s imagery is different.

Maybe eyes really are windows into the soul — or at least into the brain, as a new study finds.

The experience of life flashing before one’s eyes has been reported for well over a century, but where’s the science behind it?

A year of disruptions to work has contributed to mass burnout.

Science has not yet reached a consensus on the nature of consciousness.

Being an intellectual is not really how it is depicted in popular culture.

▸

5 min

—

with

Participants with high levels of narcissism showed high levels of aggression, spreading gossip, bullying others, and more.

Scientists successfully trained people to use robotic extra thumbs, suggesting body augmentation could revolutionize future humans.

Dreams are weird. According to a new theory, that’s what makes them useful.

The author of ‘How We Read’ Now explains.

A lab identifies which genes are linked to abnormal repetitive behaviors found in addiction and schizophrenia.

Dancing, for Nietzsche, was another way of saying Yes! to life.

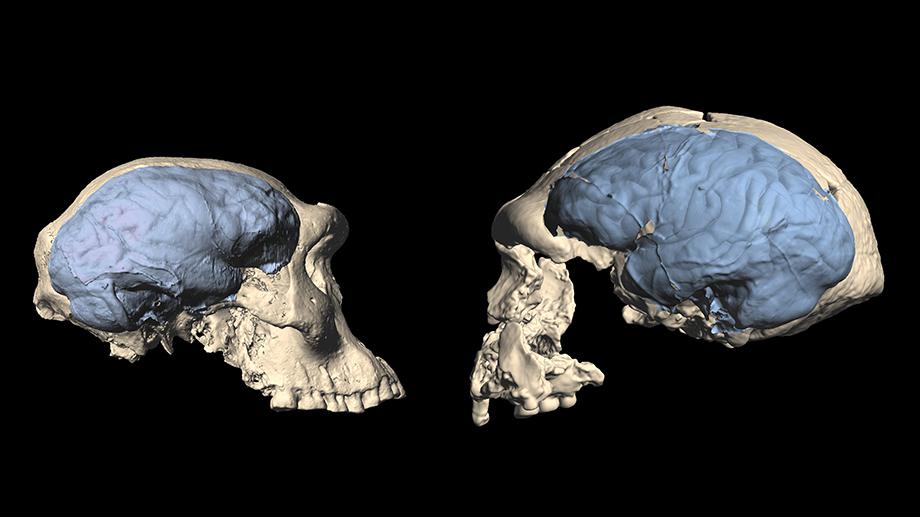

A recent study analyzed the skulls of early Homo species to learn more about the evolution of primate brains.

A new study looks at how images of coffee’s origins affect the perception of its premiumness and quality.

Research has shown how important empathy is to relationships, but there are limits to its power.

▸

11 min

—

with

Philosophers, theoretical physicists, psychologists, and others consider what or who is really in control.

▸

19 min

—

with