Literature

Neuroscientist Tali Sharot recently spoke with Big Think about a two-step method for escaping the dark sides of habits.

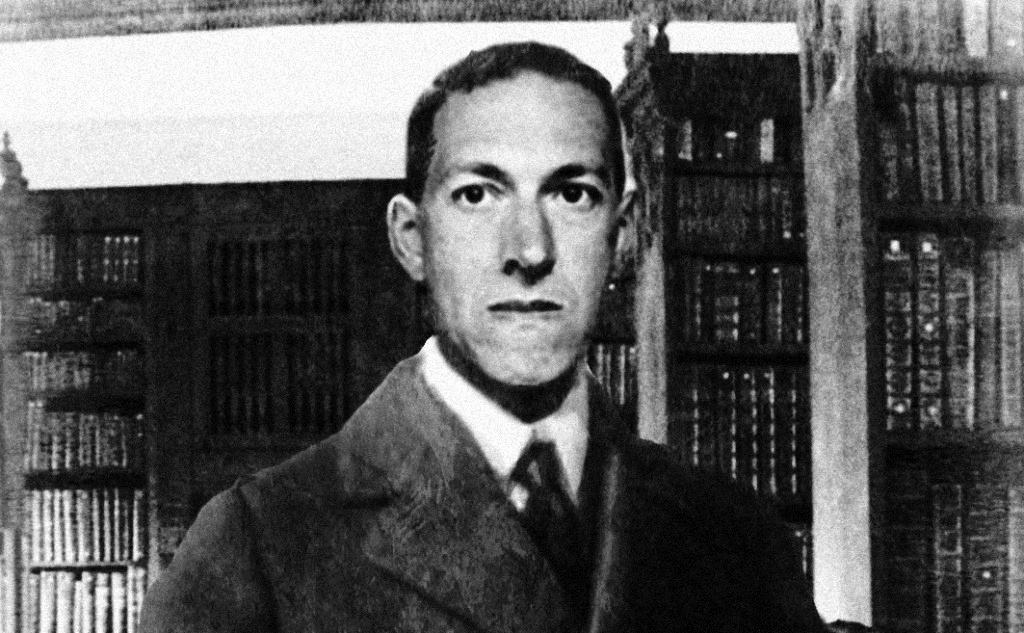

Who doesn’t love a little existential fear every once in a while?

The English writer left behind a mind-expanding collection of books.

Jokes so cheesy even French philosophers will love them.

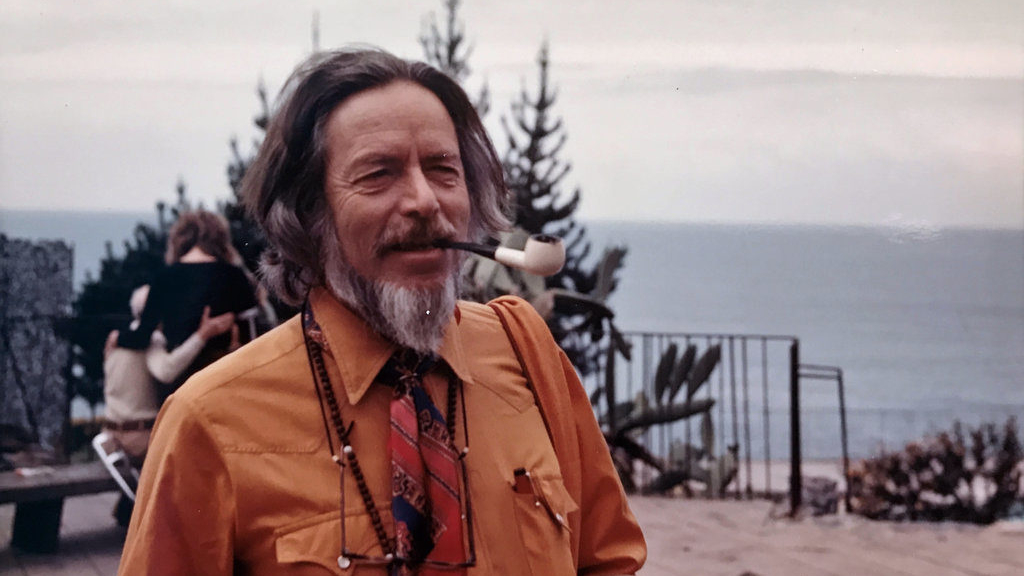

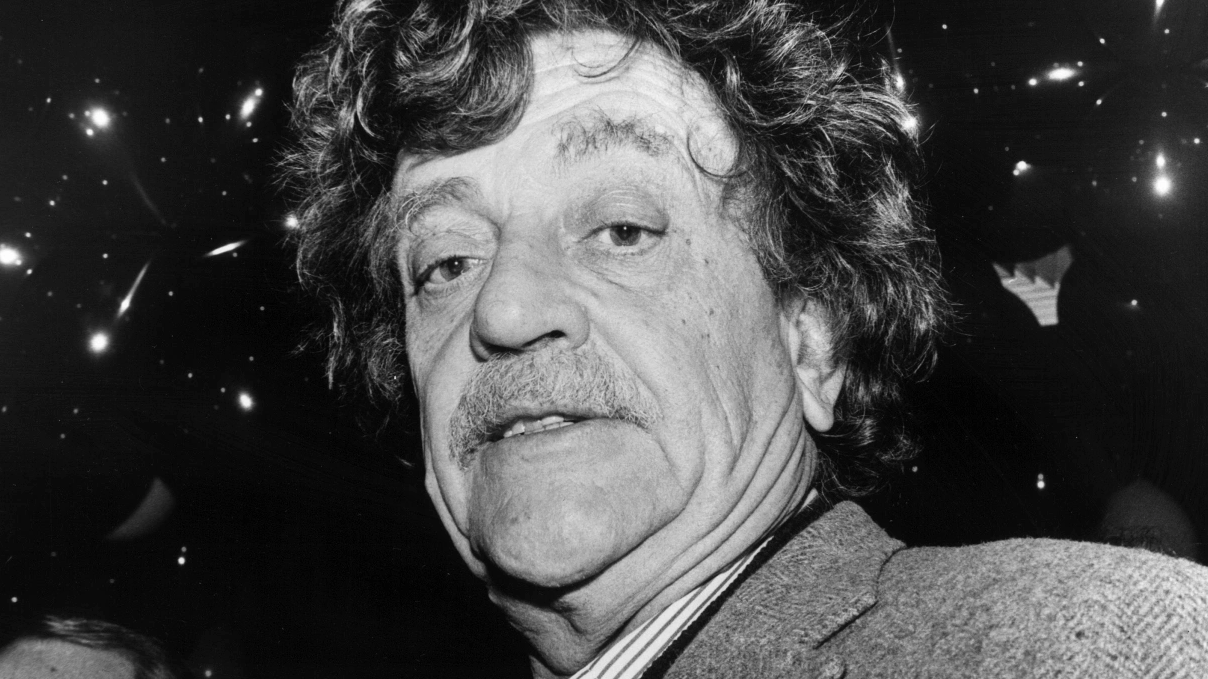

The American author said he attempted to bring scientific thinking to literary criticism, but received “very little gratitude for this.”

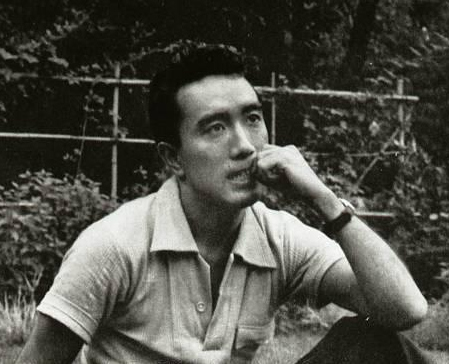

Yukio Mishima treated his life as if it were a story — one with a surprising and deadly final act.

The world is full of great mysteries. This is one of them.

Some neurology experiments — such as growing miniature human brains and reanimating the brains of dead pigs — are getting weird. It’s time to discuss ethics.

Though gloomy and dense, Russian literature is hauntingly beautiful, offering a relentlessly persistent inquiry into the human experience.

All the latest titles from the experts at MIT.

Once a book is published, who gets to interpret it? Us or the author?

Dancing, for Nietzsche, was another way of saying Yes! to life.

Scans show similar activity to what occurs when you think about yourself.

The key? A computational flattening algorithm.

Technology of the future is shaped by the questions we ask and the ethical decisions we make today.

▸

5 min

—

with

How would the ability to genetically customize children change society? Sci-fi author Eugene Clark explores the future on our horizon in Volume I of the “Genetic Pressure” series.

The rites we give to the dead help us understand what it takes to go on living.

We make school kids read “Lord of the Flies”—but it’s only half the story.

▸

5 min

—

with

She was walking down the forest path with a roll of white cloth in her hands. It was trailing behind her like a long veil. It was sweeping needles, leaves […]

WhiteSmoke Grammar Checker keeps your spelling and grammar issues at bay while also working as a translator.

From novels to movies and beyond, this 11-course bundle will jumpstart your writing career.

Two famous Italian design companies joined forces to create this masterpiece.

A general reorganisation of masculine norms interrupted the shaving-respectability regime.

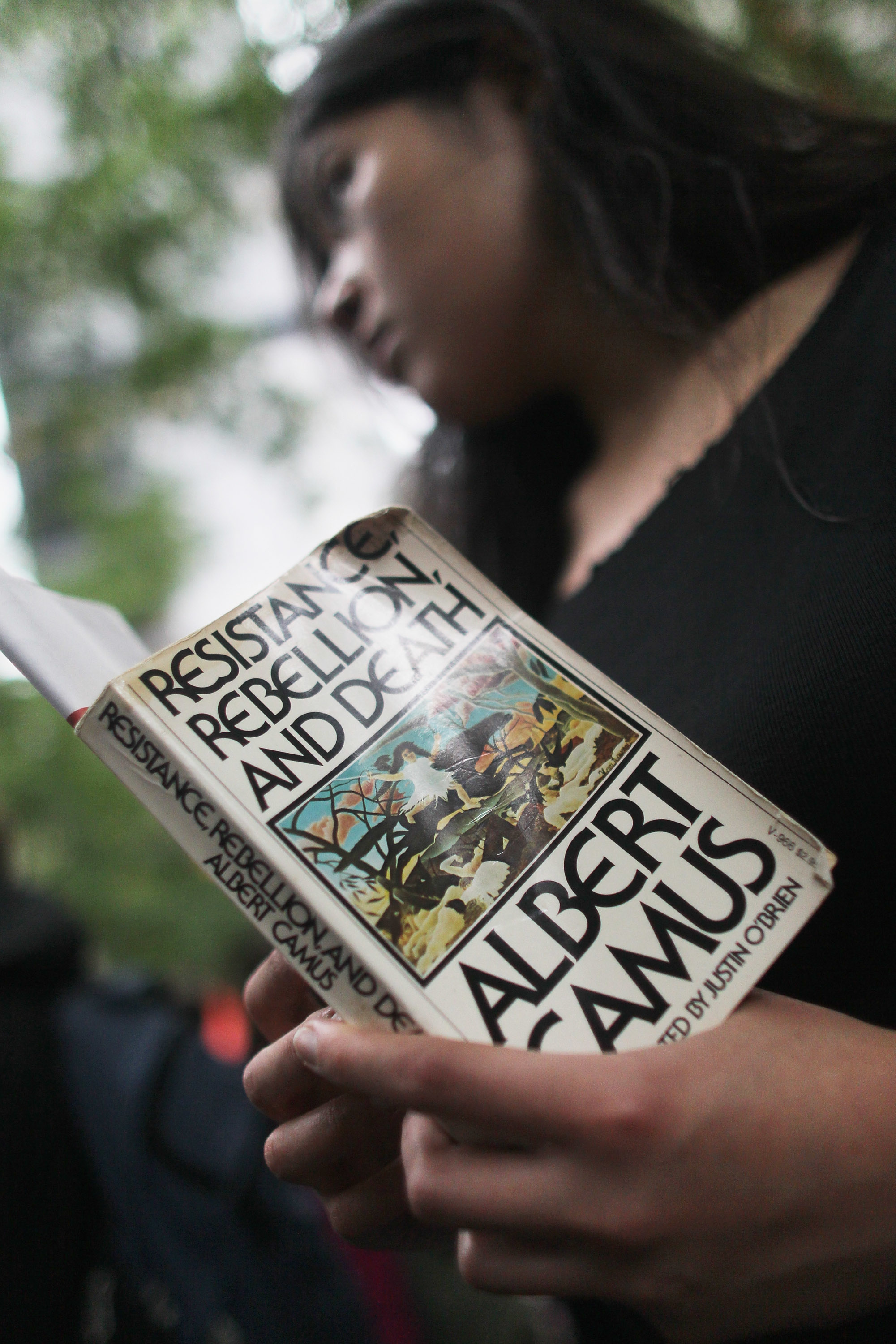

If the idea of freedom bound Camus and Sartre philosophically, then the fight for justice united them politically.

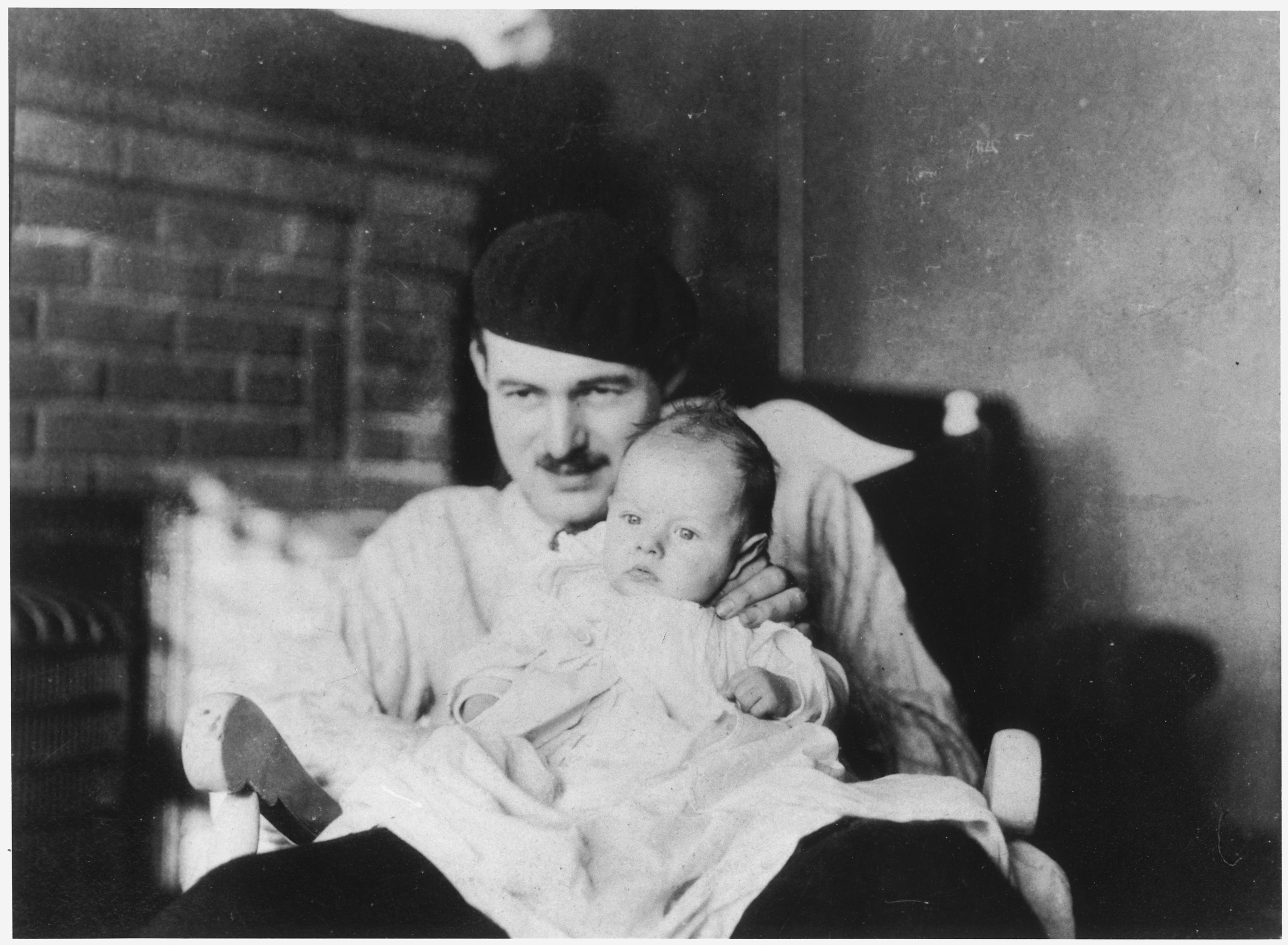

Parenting could be a distraction from what mattered most to him: his writing.

Iranian Tolkien scholar finds intriguing parallels between subcontinental geography and famous map of Middle-earth.

Join New York Times best-selling author Maria Konnikova as she leads this special edition of Big Think Live.

▸

with

We wouldn’t want to live without it, so how can we create art that’s durable?

▸

3 min

—

with

It’s normal if you’re not productive in your creativity all the time. Even the greats took breaks.

▸

4 min

—

with

Our live stream with Harvard literature professor Lisa New begins at 1 pm ET today.

▸

with