fake news

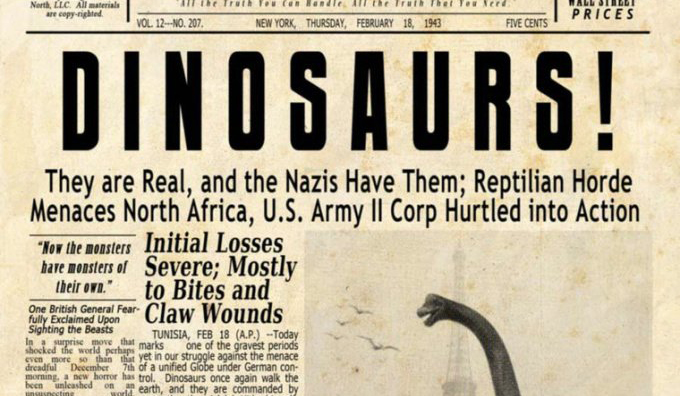

People remember when governments lie to them and it lowers their satisfaction in government officials.

This is what happens when the fringe becomes mainstream.

An international study finds the vast majority of 15-year-olds can’t tell when they’re being manipulated.

A large new study uses an online game to inoculate people against fake news.

The truth is a messy business, but an information revolution is coming. Danny Hillis and Peter Hopkins discuss knowledge, fake news and disruption at NeueHouse in Manhattan.

▸

13 min

—

with

Pope Francis’ 2018 World Communications Day message explains the dangers of fake news and what journalists and the public must do to combat it.

Here’s why your brain’s biases are a win for fake news, and a pay day for Facebook.

▸

9 min

—

with

Middle America is tired of those latte-sipping liberals and their “elite media” hanging out in New York City, but Ariel Levy makes the case that Americans aren’t as different from one another as they’d like to think.

▸

5 min

—

with

The Internet is all shadows and mirrors—but what if it were the central source of truth? Thanks to Blockchain technology, it’s a future that’s possible.

▸

5 min

—

with

Your brain stops at the most comforting thought. The truth is somewhere beyond that. Using scientific skepticism as a guide, astrophysicist Lawrence Krauss outlines the questions that critical thinkers ask themselves.

▸

6 min

—

with

Can democracy remain vibrant if the public, and especially children, don’t have the tools to distinguish sense from nonsense?

▸

6 min

—

with

Is misinformation causing outbreaks of diseases long thought curable? A recent study found that just a simple “heads up” about fake news can help save thousands of lives.

Users don’t need better media literacy to beat fake news. We need social media to be frank about its commercial interests.

▸

5 min

—

with

When the president gets his primary information from talking heads on cable TV rather than intelligence briefings, we have a problem.

▸

4 min

—

with

A new study explains why and how people choose to avoid information and when that strategy could be beneficial.

A college course on how to recognize “bullshit” addresses fake news, memes, clickbaiting and misleading advertising.

The spreading of misinformation and doubt has undermined support for climate change. Despite broad consensus from climate scientists that humans are largely responsible for climate change, only 27% of Americans think there is agreement. New research points to a possible way to “vaccinate” against this misinformation.

A careful analysis by two economists finds that phony journalism had little influence on voters and the outcome of the election.

The Trump-Russia dossier reads as though the inside of the Kremlin is a high school cafeteria where you can overhear amazing state secrets all the time, says journalist Matt Taibbi – that’s just not the way the Russians operate.rn

▸

3 min

—

with

Nowhere is anti-intellectualism more warmly incubated or does misinformation spread faster than in the online community, which is why Facebook – the third most-visited website in the world – has such a weighty responsibility.rn

▸

3 min

—

with

Did decentralizing top-down media control bring us any closer to the truth-topia we were hoping for?

▸

6 min

—

with

A recent tweet from Donald Trump plummeted the value of Lockheed Martin’s stocks. What implications does this hold about the economic influences of social media?

There is censorship in science, admits Bill Nye – but not nearly as much as there should be.

▸

5 min

—

with

Despite our romanticized vision of social media as a global town square overflowing with diversity, the reality is that each user’s experience is hyper-filtered.

“Memory is a poet,” Marie Howe once remarked, “not an historian.” When it comes to fake news, our minds can be easily and permanently misled.

Jon Stewart shares his thoughts on many issues during a recent talk with the New York Times.

Why do people believe fake news? It’s not because it gets shared all over Facebook; it’s because they don’t trust mainstream news. And Snopes agrees with them.

Don’t believe everything Google tells you. Facebook and Google are taking measures against fake news, but it’s becoming clear that it’s a symptom of a bigger problem.