experiment

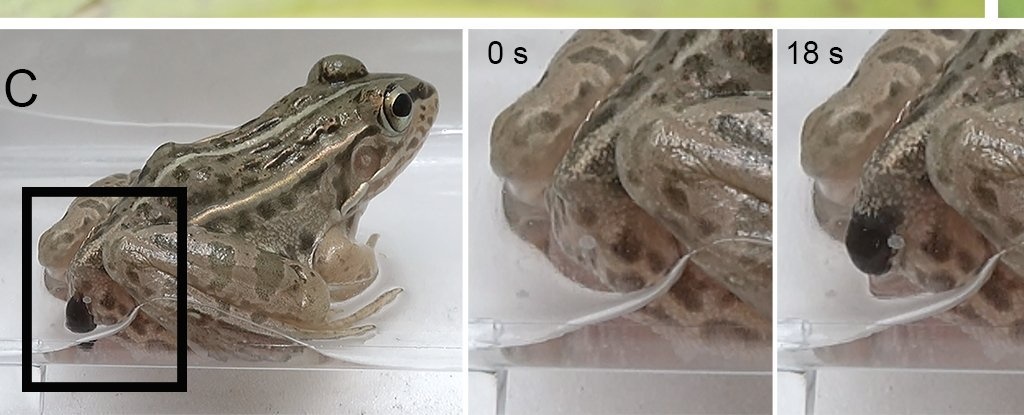

Certain water beetles can escape from frogs after being consumed.

A new study shows how reciprocal generosity can benefit you.

Blame our ancestors for why it’s easier to be a couch potato.

It’s more than just weight gain—it’s chronic inflammation and weak immunity.

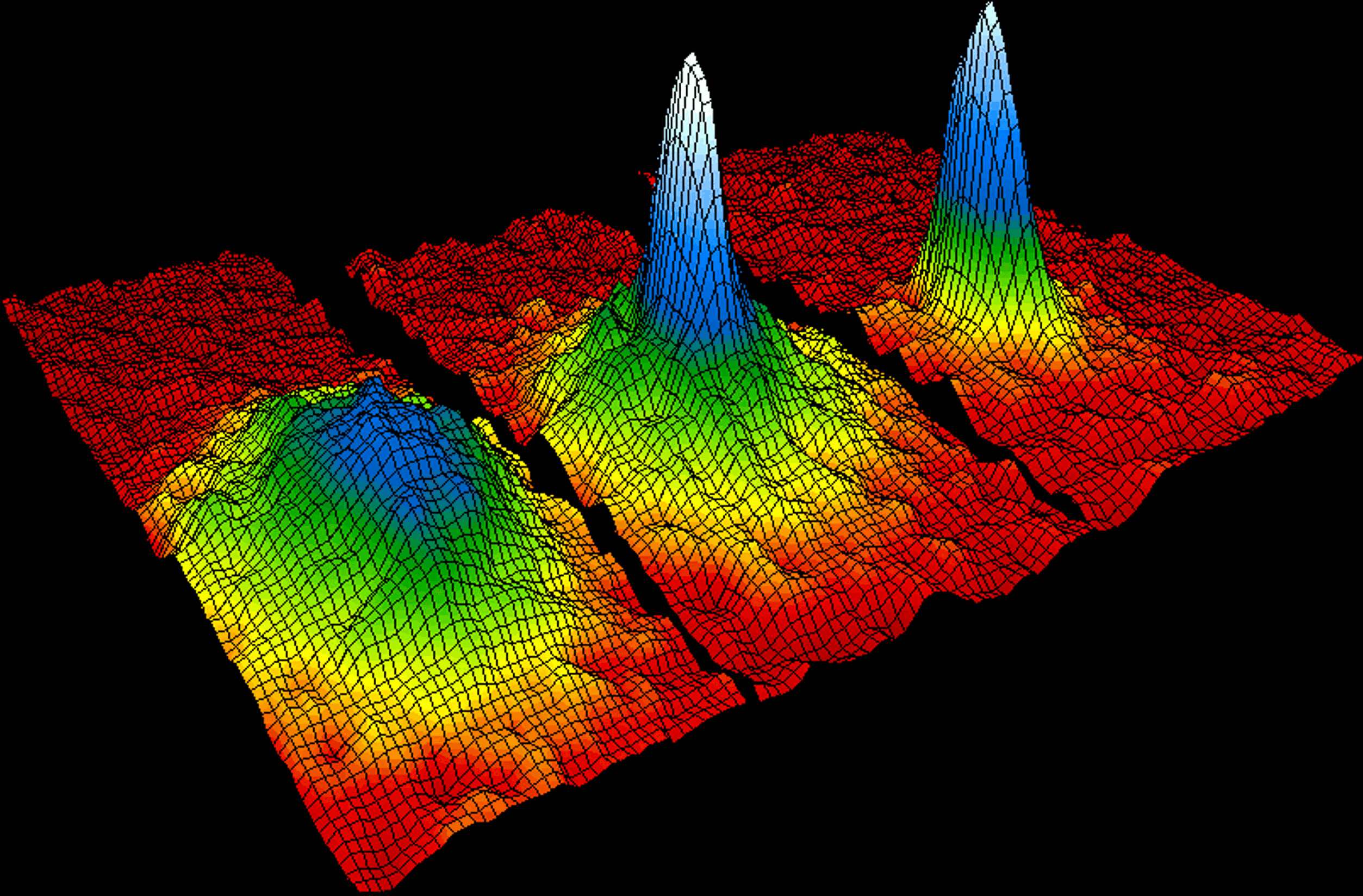

A team of researchers reverses the arrow of time in quantum experiments.

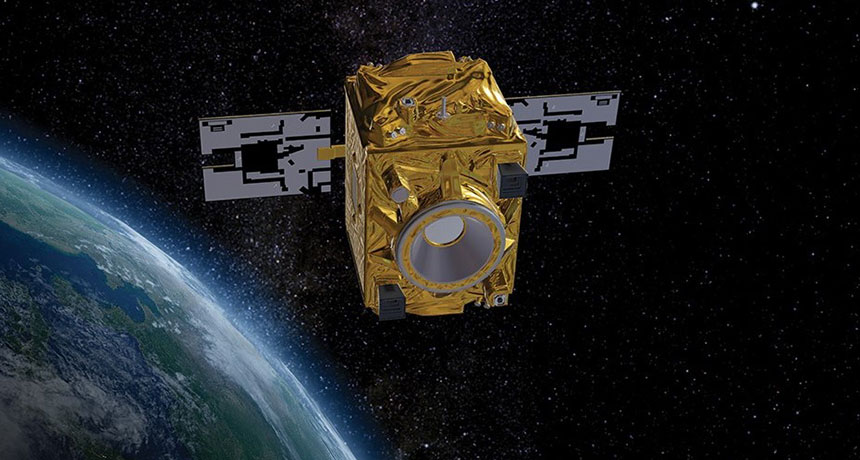

A groundbreaking experiment proves a key tenet of Einstein’s theory of gravity.

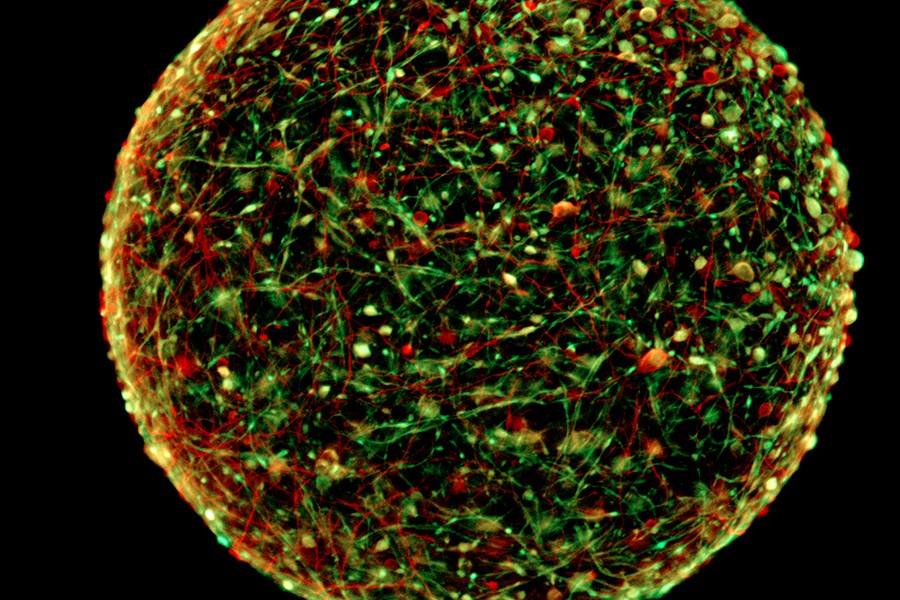

It’s the 1st observed psychedelic-caused molecular changes inside human neural tissue.

Here’s why you should always be looking for new income streams—even if you already have a full-time job.

▸

4 min

—

with

There are many people who preach the supposed benefits of psychedelics, but none do it as well, nor as reliably, as these philosophers and scientists.

What if your car was an extension of yourself? Neuroscience, art, and engineering combine to give us a glimpse of that future.

Imagine getting imperceptibly high, then playing Chinese strategy game ‘Go’. This is the experiment the Beckley Foundation will run to test the value of LSD microdosing.

Scientists create a superfluid with negative mass that accelerates backwards.

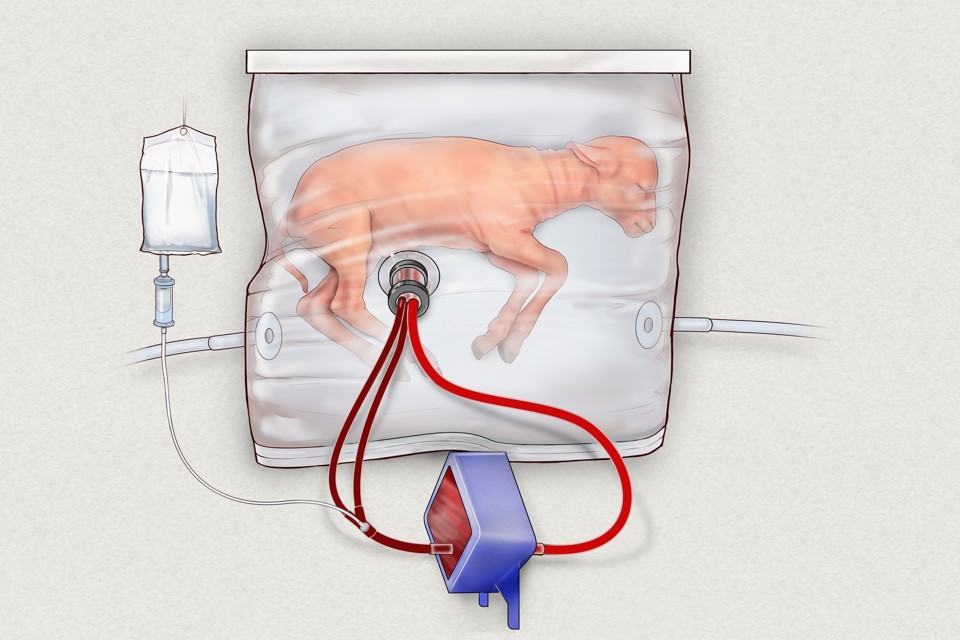

Scientists successfully test an ingenious system for growing premature fetuses.

Bill Nye is the CEO of The Planetary Society, has his own Netflix show, flew on Air Force One with President Obama, and has at least six honorary doctorate degrees. But there’s one thing that makes him prouder than all that combined.

▸

2 min

—

with

The times in history when science was deadly and dangerous.

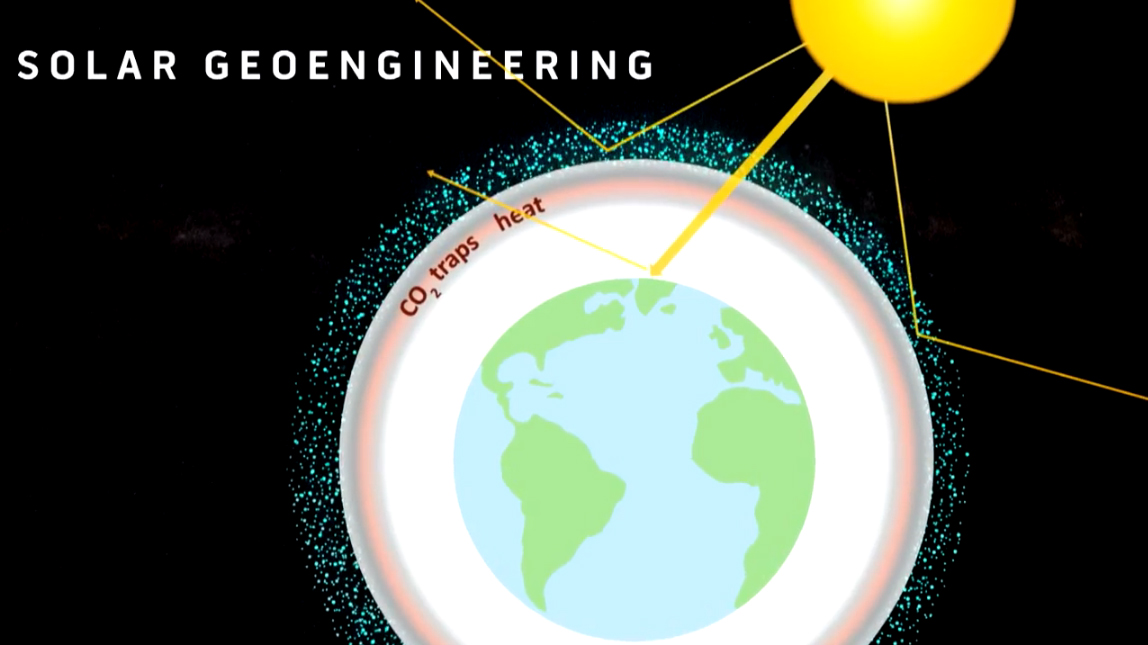

US scientists fearing for Earth’s climate future begin testing solar geoengineering. The consequences may be terrifying — which is exactly why we need these small-scale experiments.

In 1972, eight mice were placed in a utopia. Full of food, water, bedding, and space for 3000 mice. Within three years there were no survivors.

Harvard bioethics specialist Glenn Cohen considers the complex question of whether humans should mix their genetic material with other animals to create chimeras.

▸

6 min

—

with