employment

A study of 1.6 million people ties high incomes with more positive emotions and fewer negative ones, but only towards the self.

The pandemic has given us an early glimpse at how truly disruptive the fourth industrial revolution may be, and the measures we’ll need to support human dignity.

A.I. hasn’t come for our jobs just yet, but it can figure out who is looking for a new one.

Discover the peril and potential of an automated robotic world.

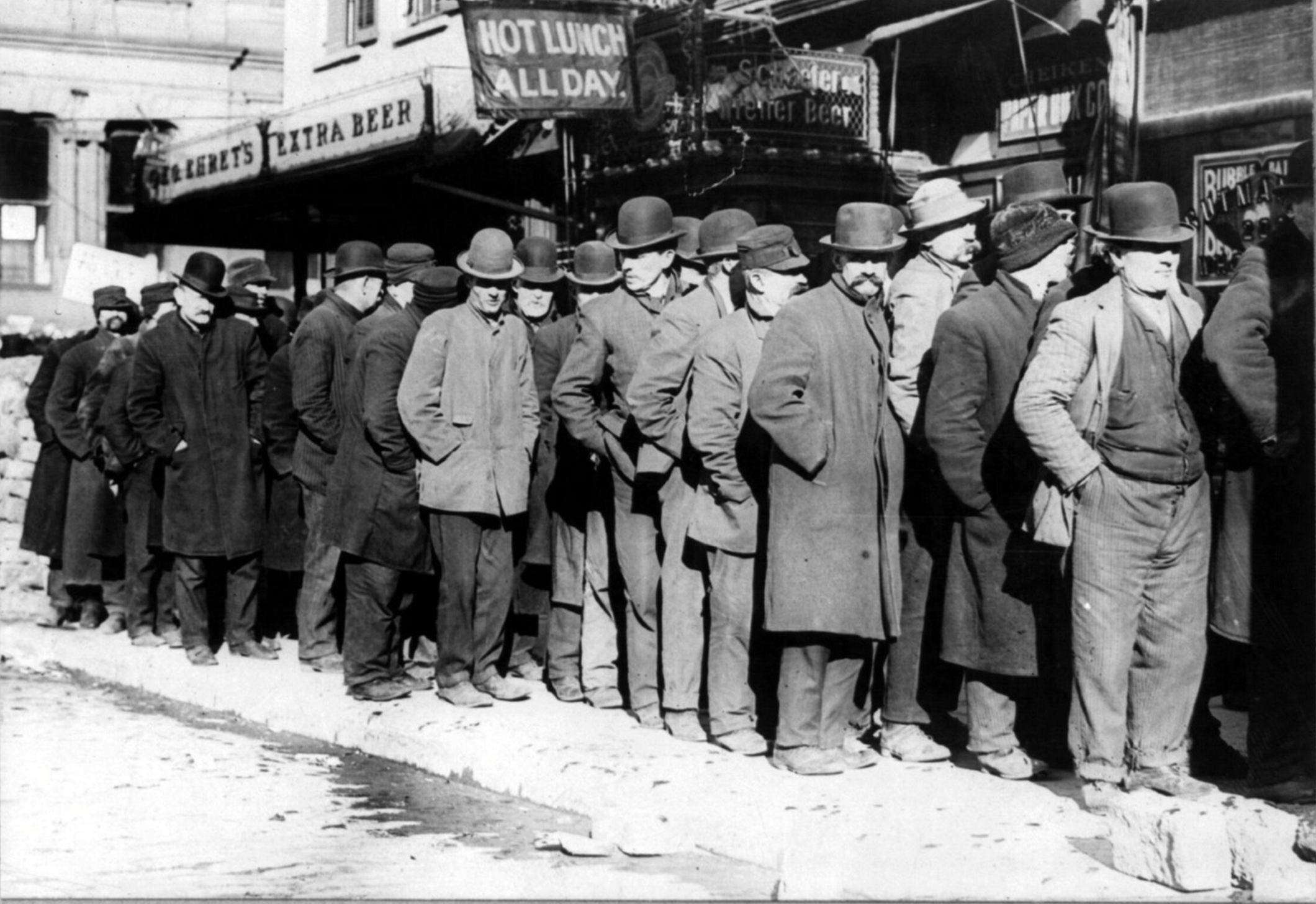

The Job Guarantee is a policy proposal that would have the state function as an employer of last resort.

An MIT study predicts when artificial intelligence will take over for humans in different occupations.

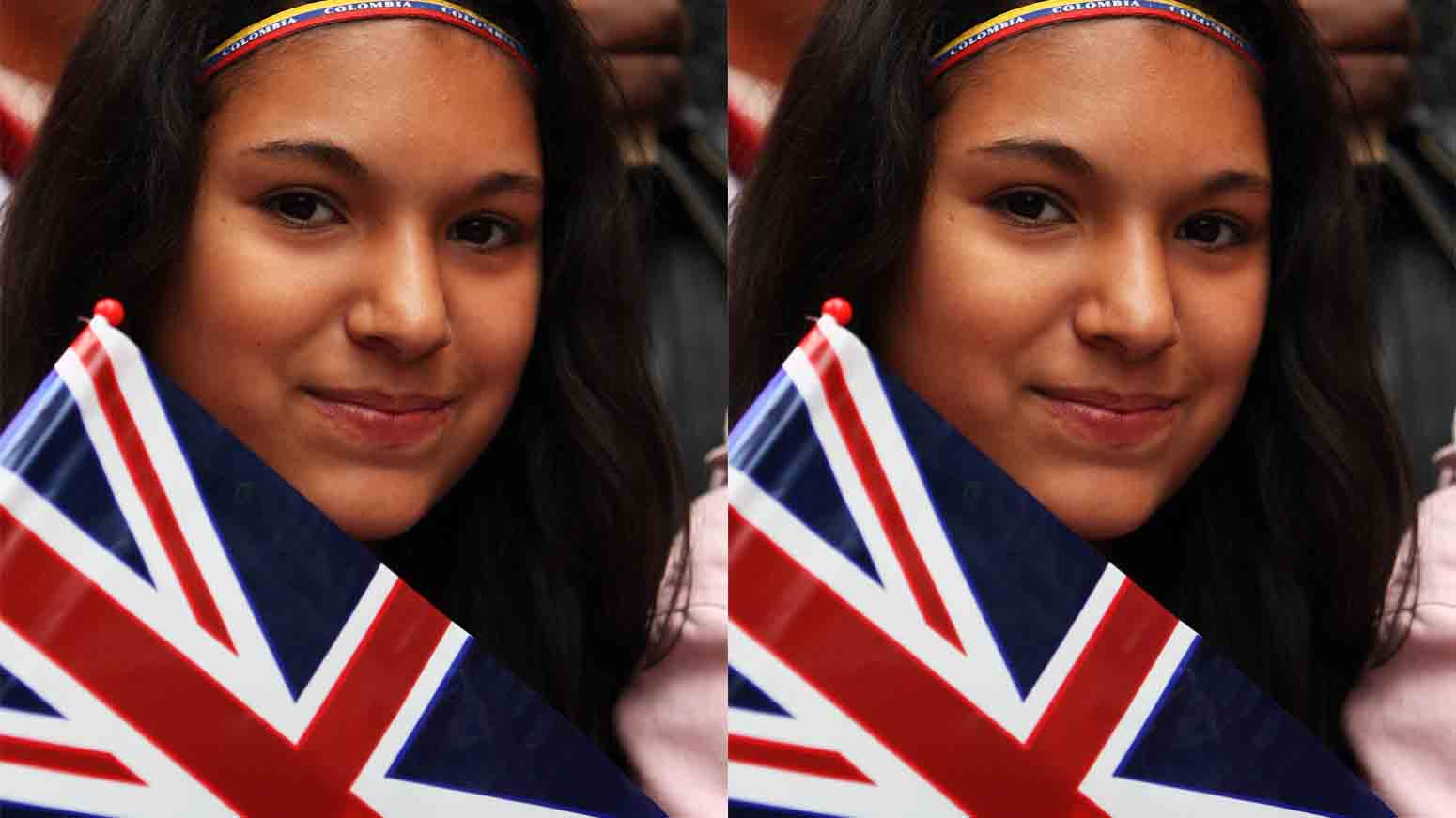

A recent study shows that migrant workers in the U.K. are three times less likely to be absent from work than their native counterparts.

A new study suggests always-improving video games are keeping young men without college educations unemployed or out of the workforce entirely.

Rates of crime and recidivism in America are very high. One Cleveland-based French restaurant, however, leads the way in helping ex-cons to thrive and not reoffend after their sentences.

Poor Americans, people in rural locations, and those with disabilities would benefit most.

The future success or failure of the economy is up to the young, and many countries could do better to equip them.

Job automation won’t be as bad as we think, so we need to learn how to stop working and prepare so we’re not dragged into the future kicking and screaming.