The Completely Locked-In Can Tell Us How They Feel For the First Time

It’s many people’s idea of a nightmare: Being so paralyzed that you can no longer communicate at all. The closest most of us have come to understanding what this could even be like would be via Jean-Dominique Bauby’s memoir and film, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. Bauby was able to dictate his story by blinking his left eyelid, his one remaining movement — he died two days after the book’s French publication. People in what’s termed a “completely locked-in state” can’t even blink.

For those of us used to being able to communicate our thoughts and feelings, it may seem impossible for someone in this state to be anything other than miserable. It’s difficult for us to even imagine the experience. And until neuroscientist Adrian Owen detected blood-flow changes in key areas within these patients’ brains in 2010, it had been largely assumed that completely locked-in patients were in a vegetative state. His startling findings suggested that they can be conscious and aware of their surroundings. Even so, they were still absolutely cut off from the rest of us. Until now.

Scientists at the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering in Geneva, Switzerland reported in PLOS Biology that they have for the first time successfully used a new brain-to-computer interface (BCI) to “interview” four completely locked-in patients. And it appears they’re glad to be alive.

Researchers have been attempting to use BCIs with the completely locked-in for some time because these devices don’t depend on muscle movement. Most of them record electrical activity in the brain using electroencephalography (EEG). Early attempts involved the surgical implantation of electrodes directly in the brain, while recent, more comfortable BCIs use electrodes on the scalp, but they don’t work well with the completely locked-in.

The Wyss Center’s BCI takes a different approach. Developed by a team led by neuroscientist Niels Birbaumer, it detects changes in the subject’s blood flow using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS).

Model wearing BCI (WYSS CENTER)

The “interview” process began with doctors asking four ALS patients to respond to yes/no questions for which the answers were known, such as: “Your husband’s name is Joachim?”

With this setup, locked-in patients were able to respond to questions with a “yes” or “no” by focusing their attention in a specific way. The two possible answers produced two distinctly different changes in blood flow, and scientists were able over time to establish with a reasonable degree of certainty (70%) which one meant “yes” and which one meant “no.”

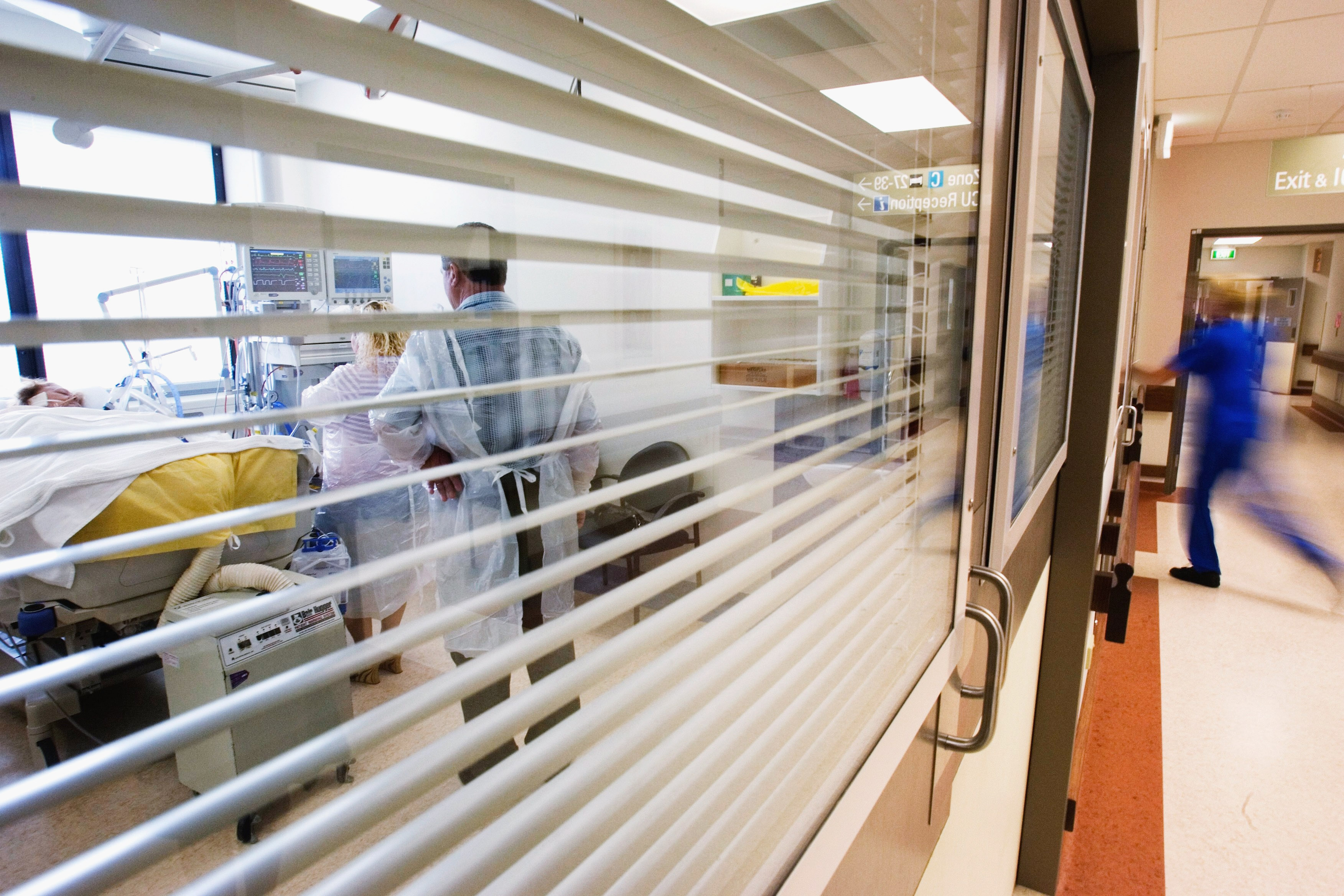

(REUTERS)

According to Wyss’s account:

In one case, a family requested that the researchers ask one of the participants whether he would agree for his daughter to marry her boyfriend ‘Mario’. The answer was “No” nine times out of ten.

Three patients were questioned during 46 sessions. The fourth — whose emotional state was judged to be more fragile based on her family’s advice — had 20, and she was asked less open-ended questions than the others.

Scientists were able to ask their subjects the Big Question: How do you feel about your life? Stunningly, three of the four subjects consistently responded “yes” to the question “Are you happy?” And when presented with the statement “I love my life,” they responded in the affirmative. Life apparently remains worth living to them in spite of their ALS.

It’s rare that a scientific result is emotionally moving like this. Imagine the relief of patients’ family members who find out that their loved ones aren’t consumed by suffering after all, and are living enjoyable lives. It’s a happy ending to what otherwise must have been an endless nightmare.

Obviously, this represents breakthrough in our understanding of what life is like for completely locked-in people. More critically, it answers the nagging question of whether their quality of life justifies continued, often expensive medical support. As the Daily Beast puts it, “All four had accepted artificial ventilation in order to sustain their life when breathing became impossible so, in a sense, they had already chosen to live.”

Birbaumer hopes to move beyond yes/no questions by further developing his BCI to allow subjects to form words by selecting letters. And the device can already be of use as a diagnostic tool for ascertaining whether ALS patients and others are in a truly vegetative state, or simply unable to communicate.