Strung Out on String Theory

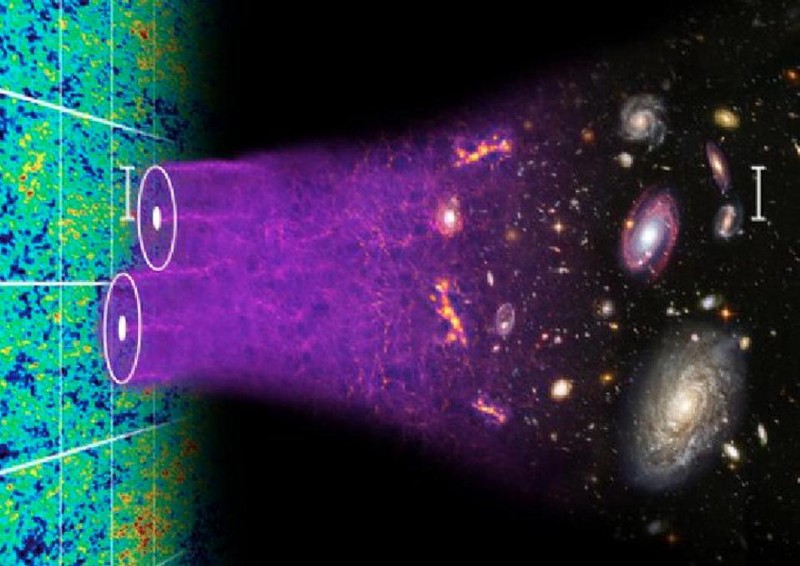

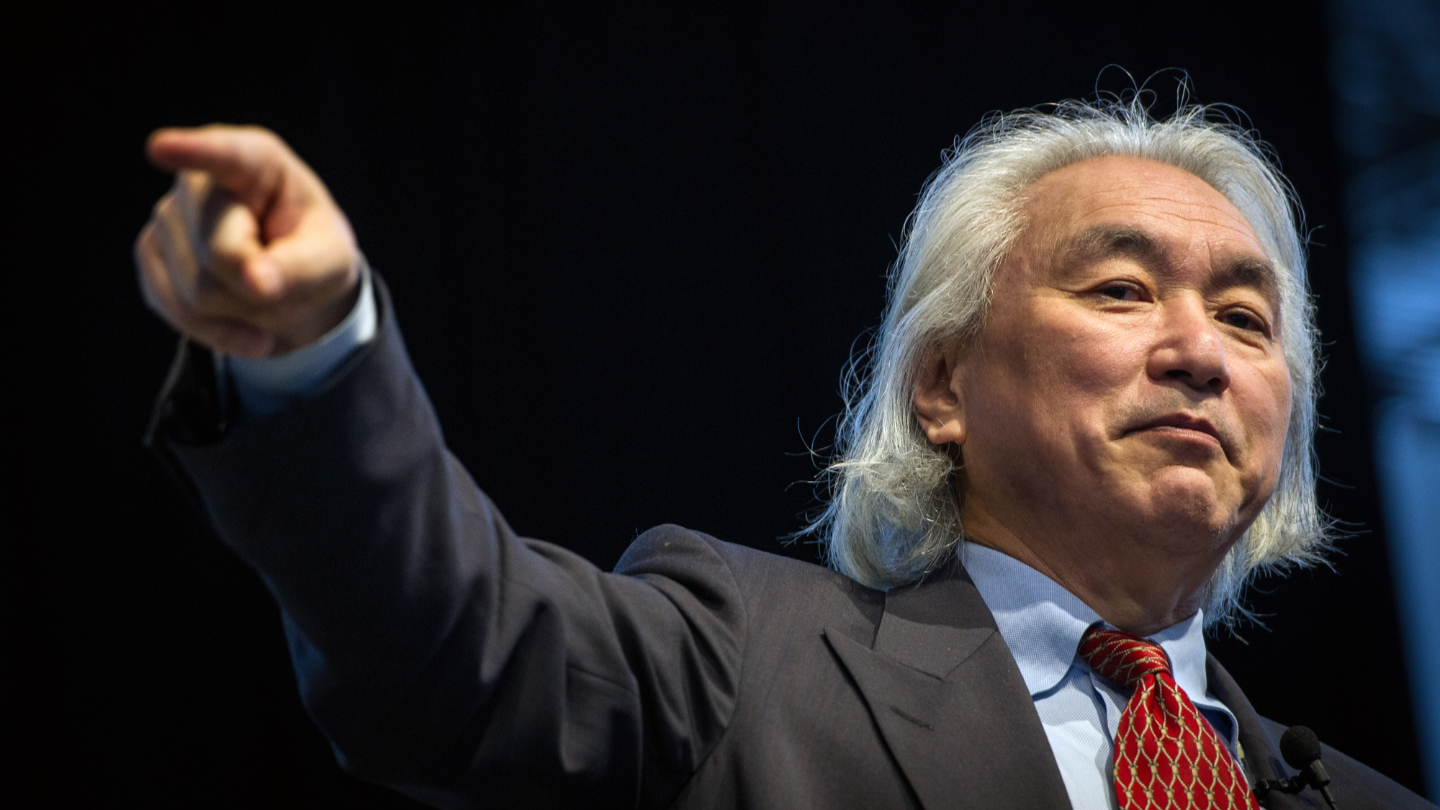

When physicist and Big Think blogger Michio Kaku explains the concept of string theory, the result is downright poetic: “Physics are nothing but the laws of harmonies on a string. Chemistry is nothing but the melodies you can play on vibrating strings, and the mind of God…would be cosmic music. Cosmic music resonating through 11-dimensional hyperspace.” Kaku holds out great hope that string theory will someday provide physicists’ Holy Grail, a Theory of Everything that “will answer the key questions: Is time travel possible? Can you drill a hole through space and time? How was the universe born and what happened before genesis itself?”

But some physicists, including Columbia’s Peter Woit, are far less optimistic. Through a book and blog, as well as a BT interview last year, Woit has waged a skeptic’s campaign against the starry-eyed promises of string theory, arguing that in its current form the theory is a dead end. Because “the problems [with it] are such that you can’t even pin it down and say this is exactly what it predicts, so let’s go out and test it,” it’s what he calls (borrowing Wolfgang Pauli’s phrase) “not even wrong.”

Woit adds that the theory’s failure to deliver on its promise—tying together the loose ends of the so-called standard model of physics—has caused a quiet shift in course among many string theorists. “The people who are still interested in it…may or may not explicitly admit that they’ve given up on the unified theory idea, but they’re often doing other things. So there’s a very active pursuit of string theory with other applications that don’t have anything to do with unification.”

Woit says he doesn’t pretend to have all the answers about the universe’s structure; he just thinks string theory may be a fizzled intellectual revolution. “There’s a lot of mathematical structure behind the standard model which is still kind of mysterious and which is not well understood, and I think pursuing that is more likely to get us somewhere than the String Theory Unification idea. Just because you’re starting from…a theory which you know is right, and trying to further develop your understand of that theory is maybe a more fruitful thing to do than trying to just throw all that out and start afresh with something more speculative.”

For physicists like Kaku, of course, speculation is part of the fun. Still, with string theory now a quarter-century old, the next generation of physicists will have to decide whether to continue pursuing its elusive threads—or return to the drawing board.