A Map of Jesus, Etched in Arabian Rock

How do you determine the value of a place? The answer to that question often reduces ‘value’ to ‘yield’: how much money does it generate? The genius loci [1] of a place is calculable by the monetary value of the crops it generates, of of the oil and gas that we frack out from under it.

There’s another way of looking at landscape, one that imparts spiritual value to specific locations. In sacred geography, both places and tracks can be holy. Famous sacred places include Delphi, Jerusalem, Stonehenge and Uluru [2]. ‘Holy tracks’ can either lead to those sacred spots, like the Way of St. James – a network of pilgrimage routes throughout western Europe converging on Santiago de Compostela; or are inherently sacred themselves, like the St. Michael Line [3], a ley line cutting straight across southern England, curiously connecting a multitude of places dedicated to the Archangel of that name.

Saudi Arabia contains sacred places in both categories: oil fields that are important economically, and the cities of Mecca and Medina, two of the holiest places in Islam, the former both as a pinpoint and as a destination. For Mecca is both the qibla, or direction of prayer for every formal Muslim prayer, and the terminus of the Hajj, the pilgrimage obligatory to each able-bodied Muslim in the world.

As Custodians of the Two Holy Mosques [4], the Saudi kings have taken it upon themselves to enforce a strict interpretation of Islamic laws and traditions in Saudi Arabia. That includes the interdiction on depicting Allah, Muhammad, his family, other prophets, and generally any living being (in descending order of taboo-ness). It also entails the exclusion of other religions than Islam from the KSA [5].

It’s not unheard of in the Middle East for different versions of the sacred to overlap, and conflict with each other. The best-known example is Jerusalem, and by extension the Holy Land: sacred in varying degrees of exclusivity to Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

By maintaining the strict and exclusive application of Islam in the KSA, the Saudi monarchy is seeking to nip such potentially explosive overlaps in the bud. But is it really tenable to reserve not just two cities for a single faith’s version of the sacred, but to police an entire nation – the 13th-largest on the planet [6] – for signs of other other truths?

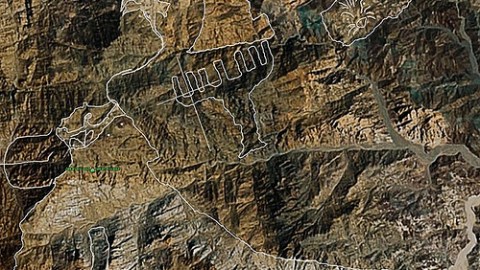

For there’ll always be people who insist on seeing things that, according to one set of values, just aren’t there. Like Jehoiada Nesnaj, a Christian visionary from Maaseik [7]. He claims to have found, in northwestern KSA, no less than 7 images that represent Jesus Christ, formed by the mountains and valleys themselves, and visible only from the air. From the official KSA position, this is doubly haram [8]: the depiction of an Islamic prophet, and propaganda for a non-Islamic religion.

The area in which the images are found is called Jabal al-Lawz, meaning the Mountain of Almonds. Some Biblical scholars think this was the Mount Sinai that Moses went up to receive his Ten Commandments; the locals apparently still call it Moses’ Mountain. Near that mountain, Nesnaj has discovered on satellite images the likeness of what appears to be a man in the outlines of the terrain.

“There is no doubt that all these images were put there by our Creator. Very significant features here are: The King’s white royal garment, crown with clear diadem, sceptre (read Book of Esther), and His [out-stretched] hand […] The book examines six more clear images to be found on that same location: Satan, Moses holding 10 Commandments, The ‘Shin’ sign (Hebrew letter for God), The Cross, The 7-branched candlestick called Menorah and last but not least an image of the Lion of Judah! All together in a 7×7 mile square area […]”.

What does all this mean? According to Nesnaj, the images prove the existence of God, and the reality of Jesus’ message:

“Is a sign in the crust of the Earth 7×7 miles [wide] big enough for you to reconsider you present ways? This one makes all the other manmade and supposed archaeological ‘Wonders of the World’ look pale!”

The images are a clever ploy by God in order to reveal his existence to us once more:

“He knew we would have […] satellites today, so He left us a message […] Our KING, of which you here see a huge image, is coming back soon to establish His new Kingdom”.

Mr. Nesnaj’s visions are a curious blend of religious conviction and pareidolia, the phenomenon by which we detect structure and meaning in (visual) data that aren’t necessarily there. The face of Jesus in a piece of burnt toast is a classic example. You needn’t be religious to experience pareidolia. Cartography-lovers also experience it – seeing ‘accidental maps’ where they weren’t meant to be (see #350, #424 and #494 for some examples discussed earlier on this blog).

Pareidolia tend to reinforce the ideas that generated them in the first place. If you’re a Bible-believing Christian, the chances that you’ll see Jesus in a piece of toast are greater than if you’re not. And when you do, you’ll probably see it as an extra reason for believing.

That phenomenon is not just limited to religious visions. An example of cartographic pareidolia similar to Mr. Nesnaj’s vision, well known in Turkey, concerns the face of Mehmet II, the Ottoman Sultan who conquered Constantinople in 1453 [9]. His profile is said to be mirrored by a piece of shoreline of that city, now better known as Istanbul.

The eerie similarity between the face of the Sultan and the city he conquered cements the relationship between the two, as it were: Constantinople was destined to be conquered by Mehmet – his face was already imprinted on its very topography…

For more on Mr. Nesnaj’s visions (and his book), go to his website here. Sultan image found here. Many thanks to G. Ockeloen for sending info on Mr. Nesnaj’s cartographic visions.

Strange Maps #586

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

__________

[1] A spirit or power inhabiting a particular location.

[2] Formerly known as Ayers Rock, this giant sandstone formation in central Australia is sacred to the Aboriginals, but also to a wider circle of New Age adherents, who see it as one of the Earth’s chakras, a concept borrowed from Indian medicine describing the human body’s energy points. Other Earth chakras include Mt. Shasta in California, Glastonbury in England, and Lake Titicaca in South America. Also, see Strange Maps #484 for a discussion of ‘useless’ Australia, in contrast to the Songlines that describe the landscape.

[3] See Strange Maps #527.

[4] The Masjid al-Haram in Mecca and the Masjid al-Nabawi in Medina. The title was previously used by the Egyptian and Ottoman Sultans, and was appropriated by the Saudi monarchy as recently as 1985.

[5] Short for Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

[6] The KSA measures 830,000 sq. mi, i.e. 2,150,000 sq. km. It is slightly smaller than Greenland, and slightly larger than Mexico.

[7] The Belgian border town that gave the world another producer of Christian imagery: Jan Van Eyck, the early-15th century painter of The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, among others.

[8] Forbidden, as opposed to halal (allowed; both terms apply primarily to food, but by extension to any and all actions considered forbidden and allowed under Muslim law; compare with a similar Jewish conceptual pair: kosher and treyf.

[9] Hence a.k.a. Fatih Mehmet, or Mehmet the Conqueror.