New ‘opt-out’ law makes every Icelander an organ donor by default

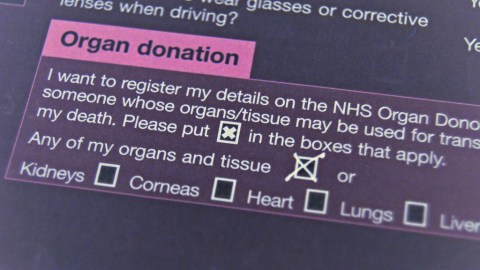

Iceland has passed a law that changes its organ donation program from ‘opt-in’ to ‘opt-out’, effectively turning every citizen into a donor unless otherwise specified.

Icelanders will still have final say on what happens to the body after death. Under the new regulations, it’s illegal for the government to “remove organs or organic material from the body of the deceased if they have expressed their opposition to such or if doing so may be deemed for any other reason to be contrary to their will.”

The law, which was first introduced by the Progressive Party in 2012, also allows for family members to opt-out on behalf of the deceased.

“In general it is a great relief for family members to know the will of the deceased and they nearly always respect their position,” Progressive Party member Silja Dögg said.

The country’s Ministry of Welfare will be responsible for informing citizens of the new law before it goes into effect in 2019.

“I want to reiterate to people to discuss their position at the kitchen table at home,” Dögg said. “This can prevent people from finding themselves in a difficult situation in case of accident or illness of a relative.”

Iceland is now one of dozens of countries with ‘opt-out’ systems, including 25 European nations like Spain, Belgium, and, as of 2017, France.

The opt-out system, also called presumed consent, poses complications for some people. Orthodox Jews, for example, believe death occurs only when the heart stops beating. That’s a problem for organ donation, considering most organs come from people who are brain dead but whose bodies still function.

There’s also some evidence that suggests opt-out programs aren’t significantly more effective at boosting organ donation than opt-in programs. One reason is family.

Research shows that virtually no doctor will move forward with an organ donation if a family member objects.

“The bottom line is, in every system—opt-out or opt-in—we were not able to find anyone that said, ‘If the family absolutely, positively said no, we would do the donation anyway,’” Dr. Dorry Segev, director of the Epidemiology Research Group in Organ Transplantation at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and author of a 2012 study on organ donation efficacy, toldU.S. News & World Report.

Although some (but not all) opt-out countries like Spain have higher donation rates than the U.S., it’s possible that other factors, like culture and religion, explain the gap.

“Our attitudes here are very different,” United Network for Organ Sharing spokesperson Anne Paschke told STAT. “Individual rights are very important in this country more so than in other countries. Opt-out hasn’t been very popular because of the way that people here view government making decisions for them.”

Among U.S. adults, 95 percent support organ donation but only 54 percent are registered donors. About 7,000 Americans die each year while waiting for a transplant.