The master and slave moralities: what Nietzsche really meant

Why do we say that helping other people is good? Why do we assume that egotistical actions are evil? After all, wouldn’t acting egotistically be good for us?

These are some of the questions Nietzsche tries to answer in his book On the Genealogy of Morality. After reviewing some absurd answers that were offered in his day, Nietzsche rejects them and starts anew, with the goals not only of answering that question, but of determining where the ideas of good, bad, and evil even come from.

In his attempt to answer these questions he draws some shocking conclusions that have tremendous implications for how we view ourselves and the lives we choose to lead.

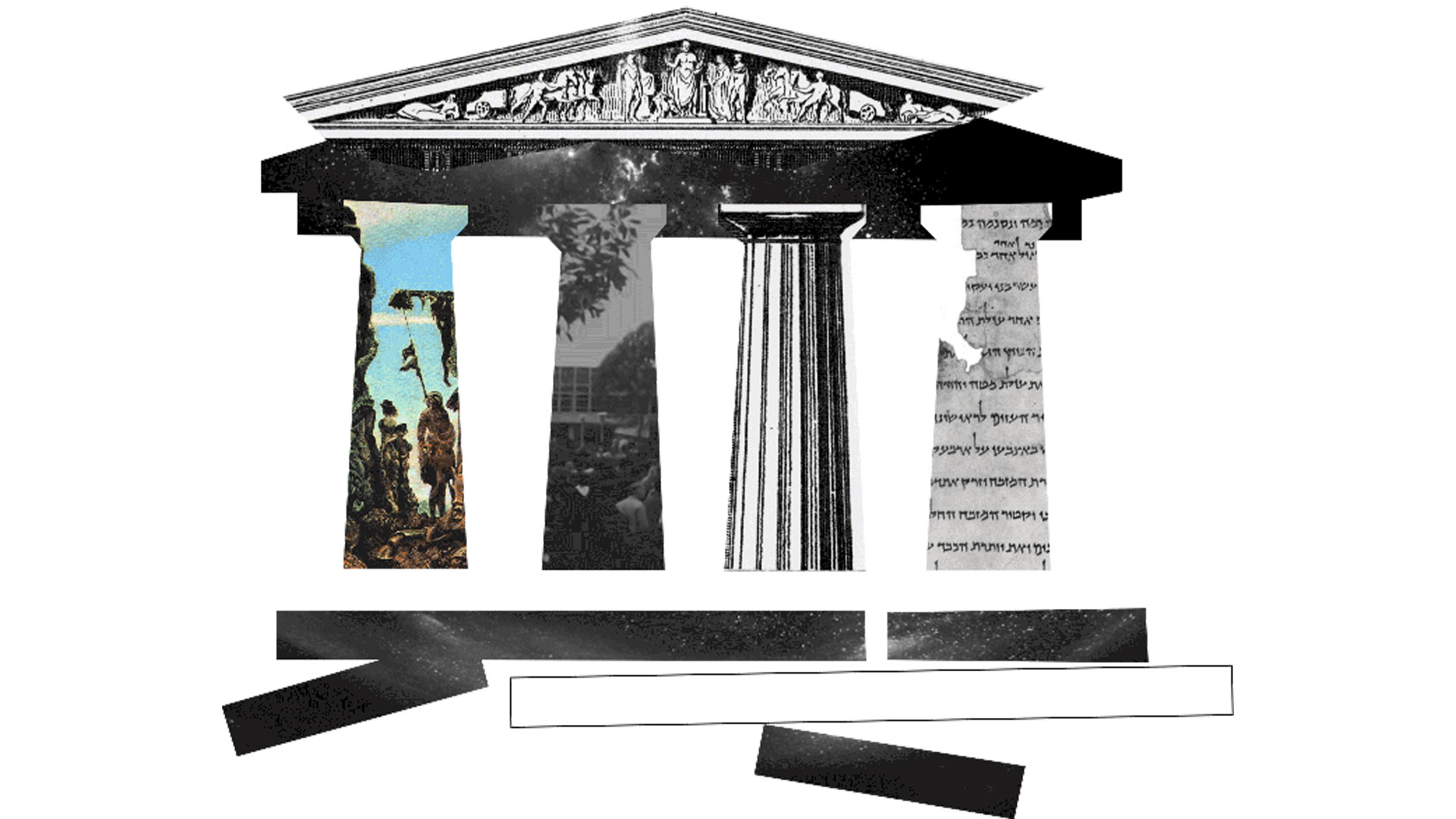

A tale of two moralities

To explain his ideas, Nietzsche gives us a story. He describes an ancient society with two classes, the Masters and the Slaves.

The Masters are strong, creative, wealthy, and powerful. They can do whatever they like. They love themselves and see themselves as good. They name the opposites of themselves, the weak and feeble, as bad. Being bad is just how a person is, they didn’t choose to be that way; they’re just losers.

The Slaves are less well off. Oppressed by the Masters, they cannot do what they like. They are weak, poor, and resentful. They initially view themselves as bad, as the Masters do, because they lack the concepts to do otherwise.

However, Nietzsche suggests that after some time, a “slave revolt” occurs. This is not a physical revolution, as the slaves are too weak for that kind of revenge, but a moral one. In this revolt, the slaves decide that they can only endure their suffering if they redefine it as both being good and a choice. The slaves begin to praise the meek, the poor, and those who are unable to end their suffering.

The Masters are dubbed evil for choosing to be wealthy, powerful, and capable. The Slaves become good for being the opposite of the Masters. This gives them the psychological strength to carry on and allows them to get back at the Masters by undermining the values system that encouraged them to exhibit their strengths.

What does the master morality entail?

The Master morality involves those with strengths of both mind and body seeing themselves as good. It values things like wealth, glory, ambition, excellence, and self-actualization. It affirms life and everything in it.

Since the master morality is favored by the powerful or those with some strength, its followers are few. However, those few are unconcerned with the disapproval of the many. This also means the masters are creative, as they have no desire to follow a prescribed life plan and are willing to experiment with new life choices that suit them despite widespread disapproval.

An example of a morality that tends towards this would be that of the Ancient Greeks. Aristotle’s ethics, for example, pay no mind to the poor and praise the powerful man who can live life fully. The Greek heroes are strong, glorious characters who make their will into reality no matter the cost. This might be why they turned the phrase “the strong do what they will, the weak suffer what they must.”

That seems a little harsh.

It is, but not all “Masters” would be vicious and oppressive. Nietzsche also places all the great artists, philosophers, and prophets in this category. This system isn’t a blank check for sociopathy, but it does have the issue where some people might need to step on others to actualize themselves. Nietzsche compares the problem to hawks having it in their nature to eat lambs. It is harsh, but it is also what the hawk needs to do to fully be a hawk.

A hawk catches a fish for dinner. Nietzsche suggests that holding both the hawk and the fish to the same morality means one of them won’t flourish. (SAM YEH/AFP/Getty Images)

What about the slave morality?

On the other hand, the slave morality condemns the strength that the hated masters possess and praises the weakness that they have. It is this act, the transvaluation of values, that Nietzsche sees as the key achievement of the slave revolt; he even praises it as an act of brilliance which succeeded in dominating western thinking for two thousand years.

After this revolt, things that the masters had were considered evil because the slaves used to lack them and the lack was made into something good. For example, Chasity was praised because the people writing the moral code couldn’t get the sex they wanted. Humility was held to be a virtue because they had nothing to be proud of. Endless generosity was praised because they needed help themselves. The slave morality is sour grapes made into a values system.

Of equally great importance to Nietzsche is the idea that the slave morality, under any guise, couldn’t stand any competing moral systems existing. Nietzsche posits that this is motivated by fear of what unchecked Masters might do. This leads to plans to take power, attempts to bring down the strong in the name of equality, the suppression of the minority who follow other moralities, the creation of stories about hell to terrify people into compliance, and the claim that the slave morality and way of life must apply to everyone.

Nietzsche thought the purest existing form of the slave morality was to be found in Christ’s teachings and explained that the Beatitudes best expressed the morality’s core ideas. He also saw the slave morality manifest in Buddhism, Democracy, Socialism, and other mass movements that sought to make everyone equal and encourage dull lives. Since the slave morality is often life-denying, he saw them all as part of the gradual slide into the nihilism which he feared.

So, Nietzsche liked the master morality best? Should we all follow that?

This isn’t likely, according to philosopher Walter Kaufman. While Nietzsche did write The Antichristleaving no doubts about his distaste for the slave morality, his descent into insanity prevented him from completing his four-part series about morality which would have included more details on the master morality. It’s probable that he would have critiqued it just as he critiqued the slave morality.

He also praised the slave morality for helping to foster the internal life of man, as the master morality, for all that was right with it, required little reflection to create.

Nietzsche’s concern was that through tools like the fear of hell, authoritarian political power, and a mob mentality people who could live their lives otherwise would be coerced into following a slave morality that they didn’t need. He understood that some people needed the comfort of the slave morality. His real objection was to the idea that we all do.

In any case, the Ubermensch, Nietzsche’s transhuman ideal, would be “Beyond Good and Evil” and not fully committed to either one of these moralities alone.

Nietzsche exhibiting the loneliness that blazing your own path often entails. (painting by Edvard Munch)

So, what can I learn from this?

What Nietzsche encourages to do is to “be noble.” While the Masters are explained to be nobler than the Slaves, a noble person could still choose to hold slavish values. Jesus Christ, who Nietzsche saw as a proto-Ubermensch, is given as an example of how that is possible.

The noble person will see their life as a project, in which they choose their own goals and drive towards them no matter what society, dogma, or the unwashed masses think. They are not afraid to have their worldview challenged or to take actions which they know are going to lead to them changing and growing as people. Nietzsche’s Superman, also known as the Ubermensch, is the embodiment of the noble way of life.

In a sense, Nietzsche’s often shocking writings can be seen as a hand extended to those of noble temperament; only the people willing to have their worldviews challenged are going to read them at all.

What can I do right now?

Ask yourself honestly, when was the last time you allowed your worldview to be seriously challenged? How many of your beliefs are mere reactions or the product of your upbringing? Are you proud of who you are and always striving to master your life? Or, are you resigned to your sorry state and letting that resignation dominate your life? Even challenging yourself with these questions is a start.

This seems a little ahistorical, is there another way to view this hypothesis?

It is also possible to view this dichotomy as a tool for analysis. Since neither of them exists in a pure form in reality, we can instead use them as idealized cases to analyze real moral systems and find out what the motivations behind their valuations are.

In Nietzsche’s campaign against nihilism, this is useful for determining which systems are life-affirming and which are life-denying when one system has elements of both moral codes.

Nietzsche was a radical thinker that wanted to examine every aspect of our worldviews. His ideas are often shocking, sometimes wrong, and always thought-provoking. Even if the master and slave moralities are better as tools for discussion than as models for historical mapping development, we can still use them to inform our lives and help promote our growth.

In the end isn’t that what Nietzsche, the great champion of self-overcoming, would have wanted?