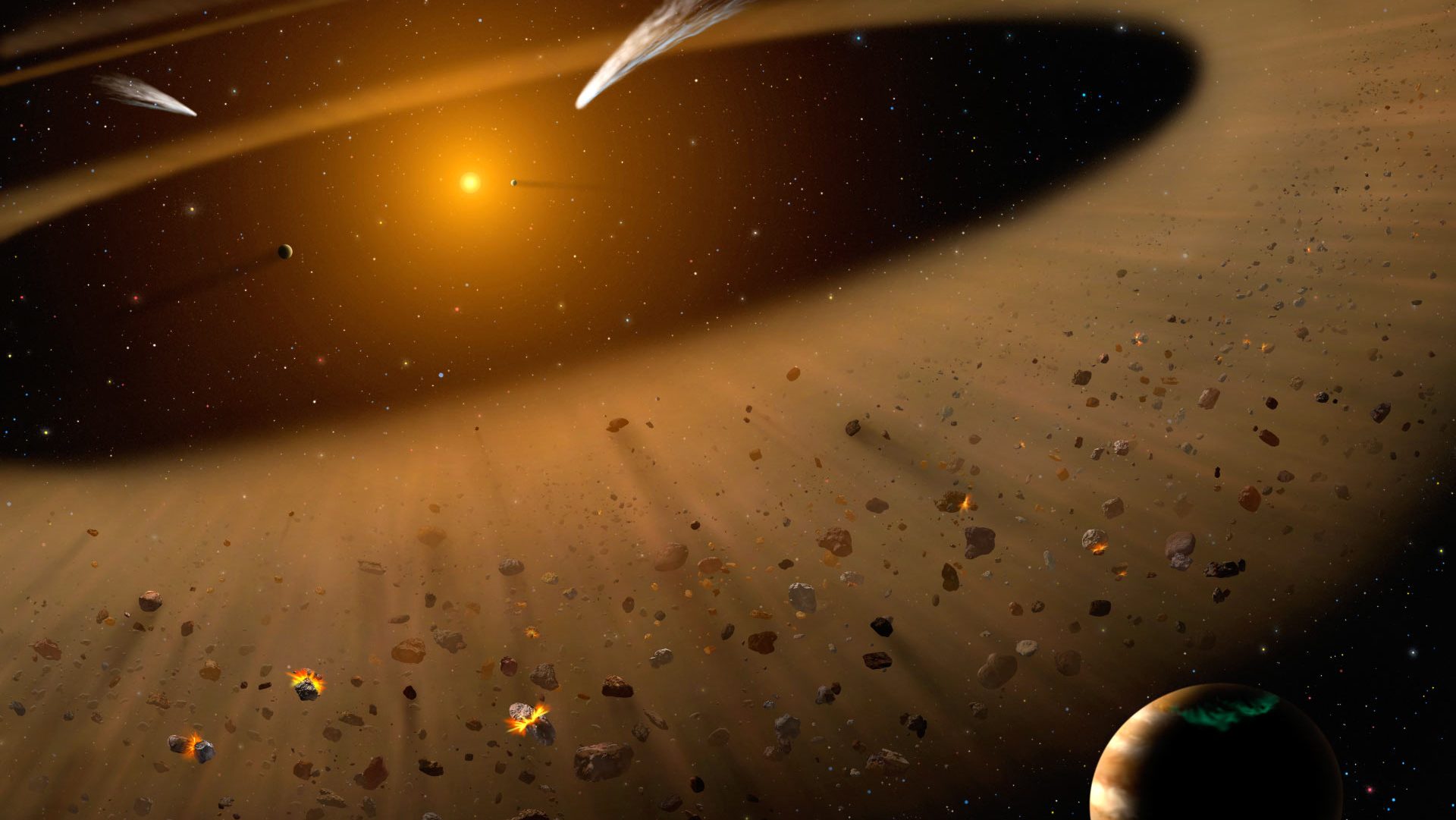

The lovely Perseids’ comet could end life on Earth

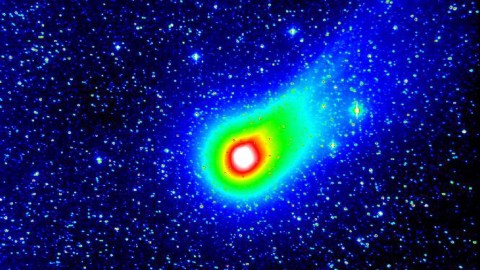

The dangerous Comet Swift-Tuttle in 1992. (Credit: Jim Scotti, University of Arizona)

The Perseids are arguably the most famous annual meteor shower. Silently streaking across the mid-August heavens each summer, it’s a profound and beautiful event for anyone with a dark sky and the discipline to just. Keep. Looking. Up. The often-exquisite shooting stars come from a comet that’s drawing ever closer to Earth. Dangerously close, actually: Radio astronomer Gerrit Verschuur has called Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle “the single most dangerous object known to humanity.” Apparently, our inspiring, transcendent meteor shower may also be the harbinger of humanity’s doom, give or take a few thousand years.

Perseids, 2013 (Credit: Flicker user the very honest man)

Why Swift-Tuttle is such a threat

Swift-Tuttle passes through our solar system at a steep angle compared to the solar system’s planets every 133 years. It swings around the sun, and as it does, melts slightly, casting off a massive debris field of ice and rock that’s estimated to grow as wide as 10 million miles and with a length of more than 75 million miles. This stuff is what rains down on us at an average of 37 miles per hour each August as what astronomers call “fireballs.” NASA’s Paul Chodas says, “The debris is coming in faster than many other comets because it’s a very elongated orbit … so that makes the show a little more spectacular because of the speed.”

Swift-Tuttle orbit (Credit: NASA/JPL)

What concerns scientists about Swift-Tuttle is that each time it passes Earth, it’s slightly closer. There’s not much change year to year, but over time it adds up. In 1992, it was 110 million miles away, but in 2126 it will be a mere fraction of that: 14.2 million miles. In 3044, it will be less than a million, a frighteningly small distance in galactic terms. Current calculations have us as probably safe until 4479, though each time Swift-Tuttle sheds materials near the sun, the comet gets just a bit smaller, and it’s possible that planetary gravitational effects will eventually alter its orbit.

Swift-Tuttle in 1992 (Credit: NASA)

And Swift-Tuttle is big, with a nucleus of 16 miles (26 km) across. It’s more than twice the size of the Chicxulub impactor, the asteroid believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs. The energy it releases could be 27 times greater than that extinction event. Astrophysicist and author Ethan Siegel writes in Forbes that a collision with Swift-Tuttle would “release more than one billion megatons of energy: the energy equivalent of 20,000,000 hydrogen bombs exploding all at once.”

NASA visualization of Chicxulub impact.

History of Swift-Tuttle

Reports of visits by Swift-Tuttle go all the way back to 69 B.C, though Swift-Tuttle was officially discovered and named in 1862 by American astronomers Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle, who both discovered it independently. The “P” in “109P” refers to it being a periodic comet. Giovanni Schiaparelli realized in 1865 that it was the source of the Perseid meteor shower.

How to watch the Perseids

The Perseids this year can be seen from August 9 through the 14th and are expected to be even more impressive—200 fireballs an hour—than usual, thanks to the pull of Jupiter. On the other hand, lunar light will get in the way early on the night of peak visibility August 11-12 as the moon is 63% illuminated in its waxing gibbous phase. Waiting until the moon sets and the constellation Perseus rises around 1 am, however, still provides a 3.5-hour optimal viewing window between 1 am and 4:20 am.

NASA’s Bill Cooke shared the best advice for catching the Perseids or any meteor shower this or any year with Space.com.

“Meteor-shower observing requires nothing but your eyes; you want to take in as much sky as possible. Go outside in a nice, dark sky, away from city lights, lie flat on your back and look straight up. [Take] your choice of beverage and snacks and things like that.”

You should plan to spend at least a few hours skywatching — your eyes won’t even fully adapt to the darkness for about 30 minutes. As Space.com puts it, “most showers only reveal their splendor in time.” And Cooke points out, “You can’t observe a meteor shower by sticking your head out the door and looking for five minutes.”