To overthrow a tyrant, try the 3.5 Percent Solution

- No democracy movement has ever failed when it was able to mobilize at least 3.5 percent of the population to protest over a sustained period

- At that scale, most soldiers have no desire to suppress protesters. Why? Because the crowd includes their family members, friends, coworkers, and neighbors.

- With a population of 327 million, the U.S. would need to mobilize about 11.5 million people to assert popular, democratic power on the government. Could that happen?

In the years after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Western democracies were giddy about the global victory of market-based liberal systems. Decades of the Cold War were over. The logic of markets, rights, contracts, and law prevailed. It was, Francis Fukuyama famously declared, “the end of history.”

But in the last decade, authoritarianism has staged a comeback. Putin and Xi have consolidated power in Russia and China. Eastern bloc nations have revived ugly forms of nationalism. The U.S. and Britain have disavowed their durable alliances and free trade. Hungary, Turkey, the Philippines have cracked down on the opposition, as have Brazil, Venezuela, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. When the U.S. deposed Saddam Hussein, Iraqis did not greet Americans as liberators.

Stunned, small-d democrats now understand the leveling, destructive power of globalism. If Twitter can be used to rally pro-democracy activists in Tahrir Square, it can also be used to spread hateful lies and revive old prejudices. Angry mobs, living in online echo chambers, can be riled into dangerous wars against democratic norms and institutions.

Can anything be done to confront the rising tide of authoritarianism? Research suggests a simple answer: Put millions of bodies in the streets to demonstrate, peacefully, for democratic values.

No democracy movement has ever failed when it was able to mobilize at least 3.5 percent of the population to protest over a sustained period, according to a study by Erica Chenoweth of Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and Maria Stephan of the U.S. Institute of Peace.

In their book, “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict“, Chenoweth and Stephan analyzed 323 political and social movements that challenged repressive regimes from 1900 to 2006. Such mass demonstrations are so visible, they found, that no one can ignore them. Their diversity and networks—with connections to schools, unions, churches, media, sports teams, fraternities, and even the military—gives them a superhuman voice and spirit. At that scale, most soldiers have no desire to suppress the protesters. Why? Because the crowd includes their family members, friends, coworkers, and neighbors.

Call it the 3.5 Percent Solution.

What is the 3.5 Percent Solution?

Let’s suppose that Americans wanted to stand up against government repression. How could everyday Americans not just speak out, but also force elites to radically change direction?

With a population of 327 million, the U.S. would need to mobilize about 11.5 million people to assert popular, democratic power on the government. Could that happen? Maybe. More than 2.6 million people took part in the Women’s March, in cities all over the country (and world), on the day after Inauguration Day 2017. The U.S. would have to mobilize four times that many to push the reluctant Washington leaders.

That would take a lot of work, but it’s possible.

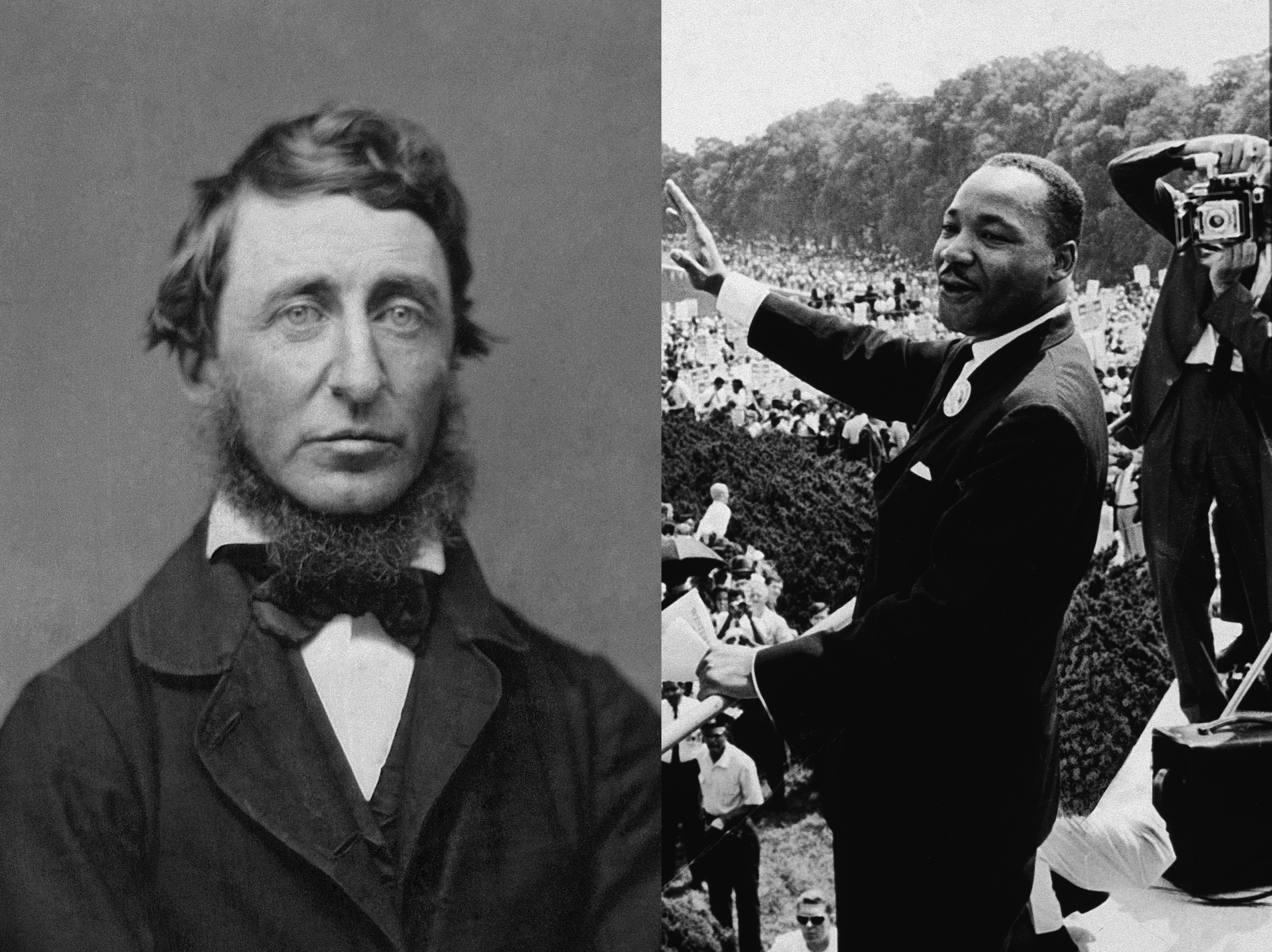

A. Philip Randolph, front center. Civil Rights leaders holds hands as they march along the National Mall during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Washington DC, August 28, 1963. The march and rally provided the setting for the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr’s iconic ‘I Have a Dream’ speech.

(Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images)

The logic of mass mobilization was first explained by a labor leader named A. Philip Randolph, who organized the black Pullman car porters in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1941, Randolph organized masses of black men to march in the streets of Washington to protest discrimination in the war industries. President Franklin Roosevelt called him to the White House, made some vague promises, and asked him to call off the march. Randolph said no, not until he got a signed executive order. Eleanor Roosevelt and Fiorello LaGuardia pleaded with Randolph to step aside. FDR dreaded the prospect of long columns of black men—maybe 100,000 of them—marching down Pennsylvania chanting about discrimination.

When Randolph stood firm, Roosevelt relented. He signed Executive Order 8802 and Randolph called off the march.

Randolph understood that reform requires activists to put their bodies on the line—peacefully. Without a willingness to be visible and accept consequences, like getting beaten or thrown into jail, the people in power do not take the opposition seriously.

“Here’s what we have to say to all of America’s men and women falling in the grips of hatred and white supremacy: Come back. It’s not too late. You have neighbors and loved ones waiting, holding space for you. And we will love you back.” – Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

As Gene Sharp points out in his three-volume masterpiece, The Politics of Nonviolent Action, regimes gain power when ordinary citizens consent to their rule. Usually, that consent is tacit, when people pay taxes, accept government regulations, and follow basic practices like sending kids to school; sometimes, it’s explicit, like adhering to court decisions and voting in elections. Nonviolent demonstrations, in effect, withdraw that consent. And no regime can survive when too many people refuse to obey the regime’s orders.

The most important demonstration of our time, the 1963 March on Washington, attracted from 250,000 to 400,000, according to crowd experts. Randolph called that march too and hired Bayard Rustin to organize it. The star power of Martin Luther King and other headliners like Mahalia Jackson, Marian Anderson, Harry Belafonte, Bob Dylan, and Joan Baez made it historic.

Roger Bannister breaks the tape as he crosses the winning line to complete the historic four-minute mile record in Oxfordshire, England. 6th May, 1954.

Photo by Bentley Archive/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images

The Roger Bannister Effect

That’s a far cry from the 11.5 million people needed for a 3.5 percent march. That’s where the Roger Bannister Effect comes in. Before Bannister broke the four-minute mile in 1954, many believed the feat impossible. Within a year, four others beat the mark. In the last 50-plus years more than 1,000 people beat it. Once people achieve a breakthrough, others duplicate it. The mind shapes what’s possible.

Such is the case with protests. Demonstrations have become as much a part of the system as elections and lobbying. In recent years, countless protests have surpassed one million. Worldwide, five million joined the women’s marches in 2017.

So think of the 3.5 percent goal, or 11.5 million people, as the political equivalent of the four-minute mile. It might seem impossible, but it’s actually quite possible.

In Hong Kong, hundreds of thousands have taken to the streets to protest China’s effort to extradite criminal suspects from Hong Kong to China, where party-controlled courts mean rigged trials. On one day, crowds were estimated to reach more than one million in a nation-state of 7.4 million residents. That’s about 13.5 percent. More typically, the marches numbered in the hundreds of thousands, hovering around the magic 3.5 percent mark. The trick is to sustain the effort. The movement has to be ready to mobilize on short notice. Succeed once and it’s easier to succeed again—not automatic, but easier.

How to protest – and succeed

Protest movements attract the greatest, most diverse crowds when they focus on the consensus goals of fairness and democracy—against brutality and corruption—and keep their protests nonviolent.

If Americans ever wanted to stage a 3.5 percent March for Freedom, then, they must embrace a message that is both specific and mainstream. In 1963, the civil rights movement made a bold call for basic human rights, against the centuries of violence and indifference to the plight of blacks. Americans today would have to adopt the same kind of simple and clear message.

What universal values might such a march champion? Start with fair elections (against foreign influence, gerrymandering, disenfranchisement, and big money). Broaden that appeal to include civil liberties, not just for Americans but for the “wretched refuse” seeking asylum and protection from civil war and life-threatening violence in other lands.

Foreign policy might offer another set of universal values to rally protesters. Most Americans support the idea of opposing brutal dictatorships and embracing democratic allies. With its vast consensus, global warming might make another focal point for rallying the masses. It depends how well the organizers frame the issue.

Specific ideas also need expression in universal outrages. In their marches for democratic revival in the U.S., protesters could cry out against specific grievances, like Russia’s cyberwar against the U.S., abuses at the U.S.-Mexico border, voter suppression, and Saudi Arabia’s murder of Jamal Khashoggi.

But getting too specific carries risks. On issues lacking a broad and deep consensus, the protesters risk alienating potential allies. So should protesters rally for Obamacare and the $15 minimum wage? Maybe, maybe not. If these issues cannot rally the masses—for the long haul—maybe they should be left off the agenda.

“Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen,” Timothy Snyder writes in his manifesto On Tyranny. “Get outside. Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them.”

The key is to make it easy for people to rally. Organize everywhere. Any place where people gather for parades and rallies—streets, parks, public squares, campuses, stadiums, auditoriums, churches, schools—get the necessary permits. It won’t be any trouble in places with strong traditions of activism; but it will take work in less energized places.

The marches should also avoid the degrading rhetoric that certain destructive forces use to attack their enemies. In 1963, organizers approved most signs people carried at the March on Washington. That’s going too far, but today’s activists should focus on a strong assertion of values, not ad hominem attacks. Protesters should avoid also the bitterness and personal attacks common in social media. It might sound old-fashioned, but keep it clean. Don’t try to “win” arguments with vitriol. Avoid tit for tat. Repeat, relentlessly, what matters: Stop the violence. Stop the lawlessness. Stop the assault on democracy.

Organizers should train marshals to keep things peaceful and nonviolent. Nonviolent movements have twice the success rate of movements that involve even occasional use of violence. But nonviolence doesn’t just happen. It’s a skill—a hard skill. But anyone who wants can learn it and will have the support of countless friends and neighbors once the big day comes.

The protests should always appeal to the better angels of our natures. Like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, we have to condemn racism but appeal to the better natures of people caught in its thrall. “Here’s what we have to say to all of America’s men and women falling in the grips of hatred and white supremacy: Come back,” AOC said. “It’s not too late. You have neighbors and loved ones waiting, holding space for you. And we will love you back.”

Students take part in a march for the environment and the climate, in Brussels, on February 21, 2019. Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old Swedish climate activist who has inspired pupils worldwide to boycott classes, urged the European Union on February 21, 2019 to double its ambition for greenhouse gas cuts.

Photo EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP/Getty Images

A protest demonstration is really a physical challenge to the regime: We’re here and you can’t push us around. We will assert ourselves. We will prevail.

No great movement can win without putting bodies on the line. “Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen,” Timothy Snyder writes in his manifesto On Tyranny. “Get outside. Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them.”

Ultimately, the greatest impact of 3.5 percent protests could be at the ballot box. Democracy, by its very definition, thrives only when lots of people go to the polls. People need a reason to vote. If a positive force does not surge through the country, people will get stuck in the better-of-two-evils mindset. That’s enervating; it’s exactly what the enemies of democracy want. The 3.5 percent demonstration is the best way possible to arouse Americans who fear for our democracy.

Civil rights activists have always known, in their heart, the truth of Chenoweth and Stephan’s argument. America’s greatest lesson in the power of protest came in the civil rights era. “It’s just like geometry,” James Bevel, one of Martin Luther King’s acolytes said. “You add this, you add this, you add this, and you’re going to get this. It’s like a law. You can’t miss with this.

“If you maintain your integrity in your heart and honestly do your work, and your motive and intention is right, and you go and seek what’s just, there is no way for you not to achieve your objective.”

Charles Euchner, who teaches writing at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, is the author of Nobody Turn Me Around: A People’s History of the 1963 March on Washington (2010) and a forthcoming book on Woodrow Wilson’s campaign for the League of Nations. He can be reached at [email protected].