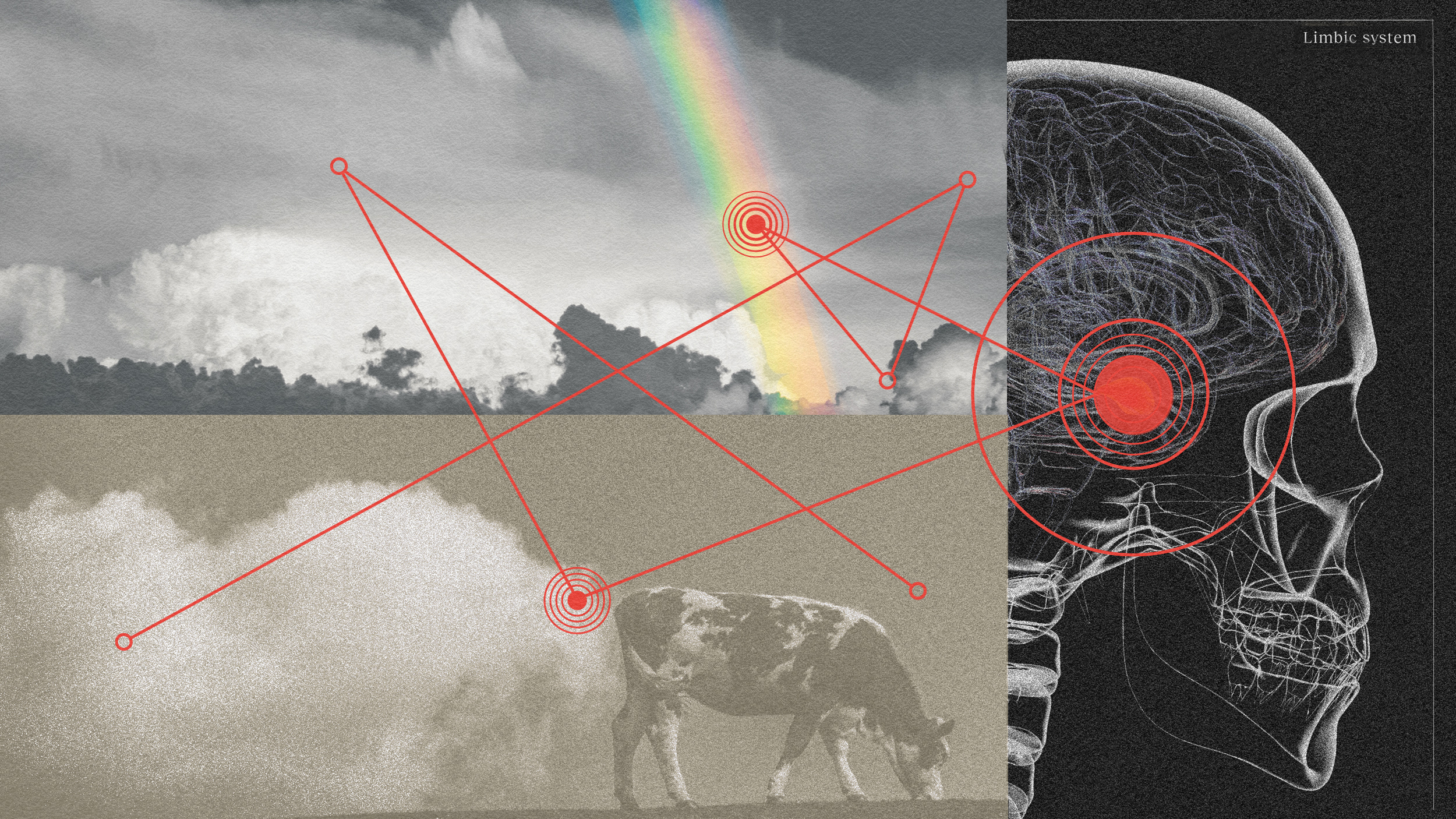

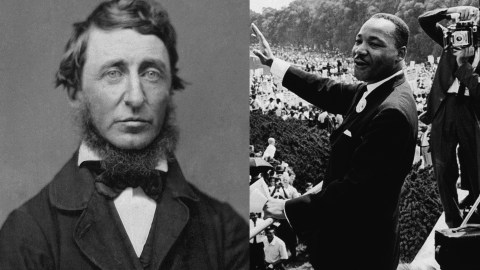

The philosophy of protest: Thoreau, King, and Civil Disobedience

(Public Domain/CNP/Getty Images)

- Nonviolent protests designed to effect change are a common occurrence around the world, especially today.

- While they may seem to be a sign of sour grapes or contrarianism, there is a serious philosophical backing to them.

- Thinkers from Thoreau to Gandhi and King have made the case for civil disobedience as a legitimate route to change.

If you’re reading this, there is a fair chance that you are either near or aware of a major act of civil disobedience happening right now. From Hong Kong to Chile, the wave of global protest movements has made headlines and tangible changes around the world. These protests have been generally nonviolent, and have focused attention on a variety of issues that plague modern society. The fact that you are probably thinking of about three of these movements right now is a testament to the power of civil disobedience.

While most people know that civil disobedience has a long and noble history, with great campaigns being carried out by the likes of Gandhi, King, and Chavez, fewer know of the serious philosophy behind the idea of nonviolent resistance. That is why today, we’ll dive into the intellectual background behind making a stand against the way things are.

The law will never make men free; it is men who have got to make the law free. – Henry David Thoreau

On the 24th or 25th of July 1846, American writer Henry David Thoreau was placed under arrest while walking to the shoemakers for refusing to pay the poll tax. While he had enough money to pay the bill, he refused to pay on the grounds that the money would go to finance the Mexican-American war, which he found to be unjust, and the institution of slavery, which he detested.

He spent one night in jail. Someone, widely believed to be his aunt, paid the bill, and he was released the next morning. He then went to get his shoe fixed.

While no lasting harm was done, Thoreau used the incident as a reason to put his ideas on lawbreaking for good to paper. The resultant essay, commonly known as Civil Disobedience, is a classic of American political thought and has influenced thinkers around the world.

Thoreau’s reasoning is easy to follow, he points out that there is such a thing as justice but that not all laws adhere to it. This presents any lover of justice with a problem:

“Unjust laws exist; shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once?

Perhaps obviously, he thinks the solution is the last one. He argues that just because the state is carrying out a particular policy doesn’t mean that the individual is obligated to sit quietly and accept it if it is unjust. Everybody has a conscience, and they must follow it.

While it is possible that waiting until the next election could be an effective method of altering the law, Thoreau reminds us that people don’t live forever and that such methods “take too much time.” Furthermore, a person who obeys an unjust law for years acquiesces to the injustice. Instead, it is just to act now and prevent yourself from being an accomplice to injustice.

As an illustration, he compares the state to a machine. While he admits that sometimes the machine might incidentally create injustices, other times, the injustice is systemic and directly results from bad policy. In such a case, the only thing for a just man to do is to “Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine.”

He further calls for us to “Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence,” rather than sit back and let the majority run things unjustly. He goes on to imagine what would happen if masses of people stopped paying their taxes while the government still uses them to promote unjust laws and notes that it is more likely that there would be policy changes then mass arrests.

While it might look like Thoreau is just trying to get out of his taxes, he says explicitly that he would be happy to pay a highway tax, since that only helps people. However, since he cannot trace the route of his money as it works its way through the bureaucracy, he finds it better to avoid showing allegiance to the state at all through paying anything.

If you are noticing a few radical notions here and there, you’re not seeing things. Thoreau’s ideas are part of the foundation of the school of thought known as individualist anarchism. This school, like many strains of anarchism, views the state as “expedient” at best and a threat to freedom and dignity at the worst. While Thoreau wasn’t a bomb thrower, he notes in his essay that the American Constitution has many excellent features, he firmly believed the state would wither away as society advanced to a point where it was no longer needed.

He is also an influence on the schools of anarcho-pacifism, green anarchism, and anarcho-primitivism.

The lasting influence of Civil Disobedience

The essay directly inspired Mahatma Gandhi, whose brand of nonviolent resistance to British rule in India would inspire Martin Luther King Jr. and Cesar Chavez in the United States. Dr. King would write his own essay, The Letter from Birmingham Jail, expanding on the same themes.

King’s arguments are less anarchistic than Thoreau’s, but the basic principals remain the same; there is such a thing as justice, a person has no obligation to follow an unjust law, and a person is morally obligated to break a law that promotes injustice.

Dr. King’s letter, written while in jail as opposed to just after leaving, also adds a strategic element to the analysis of nonviolent protest.

“You may well ask: ‘Why direct action? Why sit ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?’ You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood. The purpose of our direct-action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.”

As you can see, King believes that nonviolent demonstrations can bring ignored issues to the forefront of public opinion. It is then possible for progress to be made on those issues. This idea isn’t totally unique to King; a similar philosophy was used by Emmeline Pankhurst during the suffrage movement, though she was much more open to destructive tactics.

Nonviolent resistance has a long and noble history of creating positive change without resorting to destruction. Thinkers like King and Thoreau make excellent arguments as to why we should not be content with injustice and slow progress but should instead take action to improve our situation.

So next time a protest march inconveniences you, remember that the participants are carrying on a well thought out tradition, and maybe try to hear them out before you dismiss them.