Speaking Multiple Languages Changes Your Perception of Time

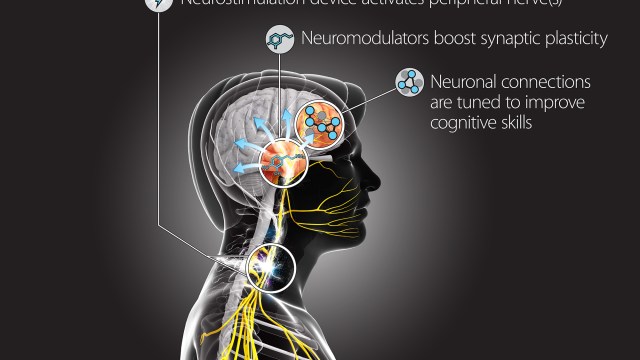

As adults we process language so quickly it’s easy to overlook the neurological complexity of speaking and understanding. In How Language Works British linguist David Crystal breaks it down into five major steps:

If we had to stop and contemplate these steps every time we wanted to order a coffee we’d never get caffeinated. Fortunately once we begin learning grammar at around eighteen months, moving from single word commands to the rich world of nouns, verbs, and adjectives, unconscious control mechanisms take over.

Language is cultural. How we understand the world is embedded in how we speak and understand the language we use. Yet each language is also a philosophy, a way of understanding the world. Grammatical rules are not only for speaking, but for contemplation.

New research published in The Journal of Experimental Psychology: General looks at how we understand time through the languages we use. Interestingly, the researchers—Lancaster University’s Panos Athanasopoulos and Stellenbosch and Stockholm University’s Emanuel Bylund—discovered bilingual speakers experience time differently than monolinguists.

As is commonly known, bilinguals code-switch constantly, shifting from language to language depending on the situation they encounter. Yet how you express something in one language might be drastically different than how you’d say it in another.

In the study the professors cite the fact that English and Swedish speakers mark time by physical distances, such as “short break” and “long wedding.” Greek and Spanish speakers consider volume instead: “small break” and “big wedding.”

Byland and Athanasopoulos wanted to know how much time had passed for Spanish-Swedish bilinguals, so they either used the word duración or tid, the Spanish and Swedish words for “duration,” while they looked at containers on a screen.

When asked in Spanish the bilinguals focused on how full the containers were: time as volume. Yet lines were also growing on the screen during this process. Prompted by the Swedish word bilinguals instead focused on those lines, negating how full the containers were.

Professor Athanasopoulos realized bilinguals are exposed to perceptual dimensions they might have been blind to before:

The fact that bilinguals go between these different ways of estimating time effortlessly and unconsciously fits in with a growing body of evidence demonstrating the ease with which language can creep into our most basic senses, including our emotions, our visual perception, and now it turns out, our sense of time.

He finds bilinguals are more cognitively flexible than monolinguists, which affords them advantages on learning and multitasking and even, he speculates, mental well-being. Given that one of the best things adults can do to stave off diseases of dementia is learn a new language (as well as a musical instrument, its own form of language), it makes sense bilinguals have stronger and more flexible brains. As in so many cases in life, diversity wins out.

—

Derek’s next book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health, will be published on 7/4/17 by Carrel/Skyhorse Publishing. He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.