How the Diderot Effect explains why you buy things you don’t need

In 1765, Russian Empress Catherine the Great heard that the philosopher Dennis Diderot was in dire need of money. As a well-known patron of the arts, sciences, and Enlightenment philosophers, she immediately purchased his entire library. She directed him to keep it at his home and hired him as her librarian with 25 years of salary upfront.

Diderot, whose finances had never been sound, proceeded to use some of the money to buy a very lovely scarlet robe.

This is where his troubles began. After he got used to the splendor of his new garment, he noticed that his apartment wasn’t quite as nice as it should be now that he was wearing beautiful clothes.

To fix this, he replaced his old prints with new ones. Then he noticed his armchair was no longer suitable and replaced it with a new leather one. His desk was then suddenly out of place and needed to be updated as well.

Before long, he had replaced nearly every item in his home with a shiny upgrade. In the end, he was in debt and still hungry for more material goods.

He describes his descent into materialism in his essay Regrets for my Old Dressing Gown. This spiral of consumption is now known as The Diderot Effect, as he was the first to describe it.

What is it?

The Diderot Effect is a two-part phenomenon. It is based on two assumptions about our shopping habits. Those ideas are:

- Goods purchased by customers become part of their identity and tend to complement one another.

- The introduction of a new item which deviates from that identity can cause a spiral of consumption in an attempt to forge a new cohesive whole.

Both of these ideas are on display in Diderot’s essay. He explained that the first robe was part of his identity as a writer:

“Traced in long black lines, one could see the services it had rendered me. These long lines announce the litterateur, the writer, the man who works. I now have the air of a rich good for nothing. No one knows who I am.”

He was also aware of how that one garment was part of a larger whole, explaining:

“My old robe was one with the other rags that surrounded me. A straw chair, a wooden table, a rug from Bergamo, a wood plank that held up a few books, a few smoky prints without frames, hung by its corners on that tapestry. Between these prints three or four suspended plasters formed, along with my old robe, the most harmonious indigence.”

But when he introduced the new robe there was “no more coordination, no more unity, no more beauty,” leading to the spiral of consumption.

As modern sociologists now understand, his getting even a single item that broke his theme lead to an attempt to replace everything in his room to match the splendor of his new robe.

What can this effect do to me?

In the case of Diderot himself, it leads to a vicious cycle of consumption that nearly bankrupted him. While this was an extreme case, made worse no doubt by being made suddenly well off after a lifetime of limited means, the rest of us still need to be wary of where one out of place purchase can lead.

At the very least, the Diderot Effect can make us desire things we don’t need to provide a more seamless association between the things we have. As anybody who has bought a new shirt only to need new shoes, pants, and ties to match knows, this spending can get out of hand in a hurry.

How can I avoid being taken in?

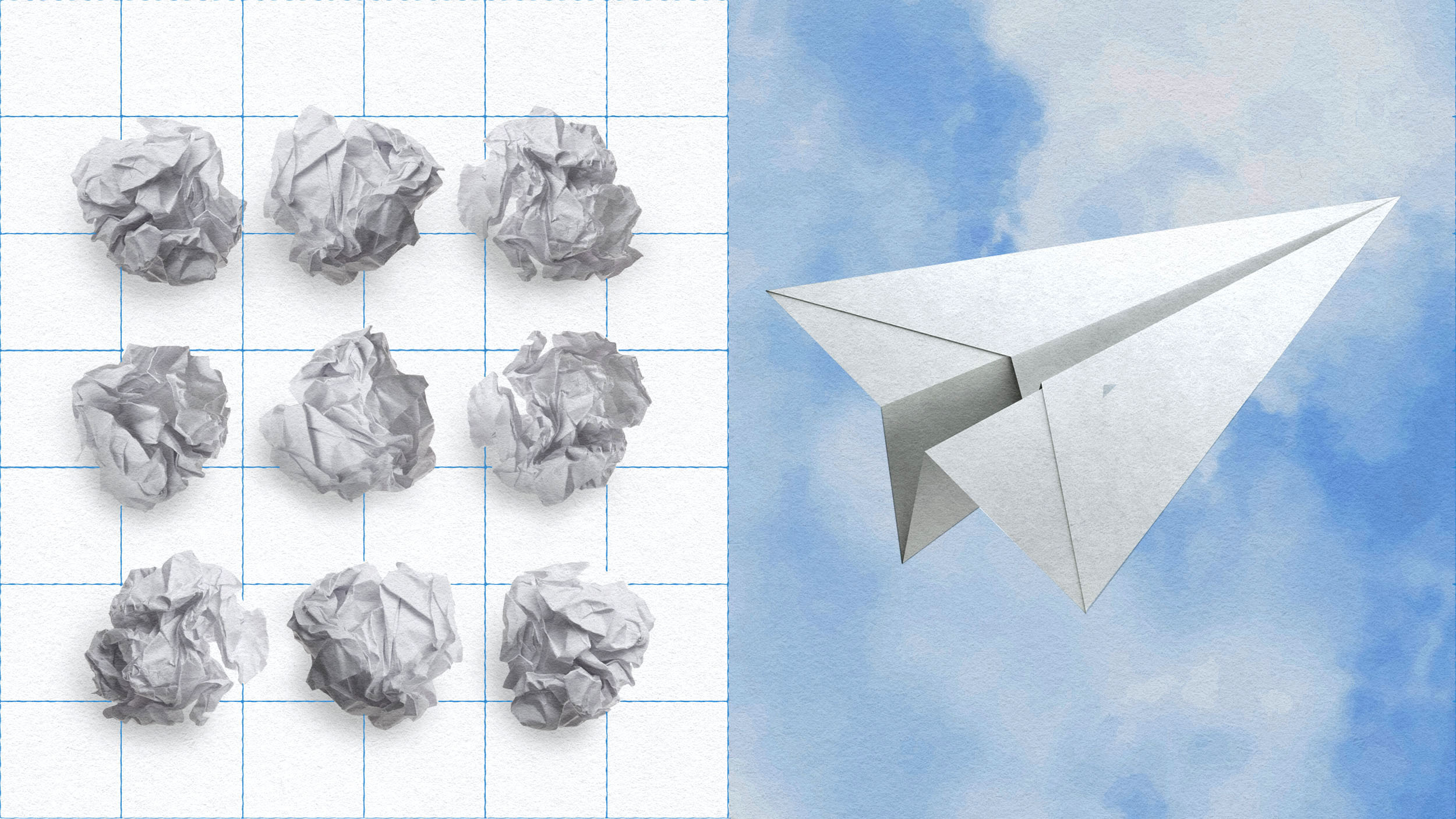

As with many vicious cycles, the best thing to do is not start the cycle at all. Diderot only had a problem because he bought the first robe. Without it, there wouldn’t have been any problem.

There are many ways to reduce your consumption. Even something as simple as avoiding the temptation to shop can be enough to stop the Diderot effect before it starts. It can also help to change your thinking when replacing an older item with a newer, flashier, version. Instead of thinking of it as an upgrade, consider it as a mere replacement.

Since this effect also applies to other people, maybe make sure your gifts to others aren’t going to cause them to want to redo their entire living room.

Does this tie into any other philosophy?

Diderot himself only ventured into this subject once and he is much more famous for his work on the Encyclopédie. The concept has influenced some critiques of capitalism since then and has recently become a topic in sociology and psychology.

It also serves as an excellent example of why pursuing desire won’t necessarily lead to happiness, as Buddhism teaches us. In cases of material goods at least, one purchase fuels the desire for the next.

While most of us will never have to worry about getting an influx of wealth from the Empress of Russia, the Diderot Effect can still torment us all. As with many things, being aware of the tendency of one purchase to lead to another might not be enough to stop us from getting taken in all the time, but it might help us avoid Diderot’s situation.