Sex & Relationships

All Stories

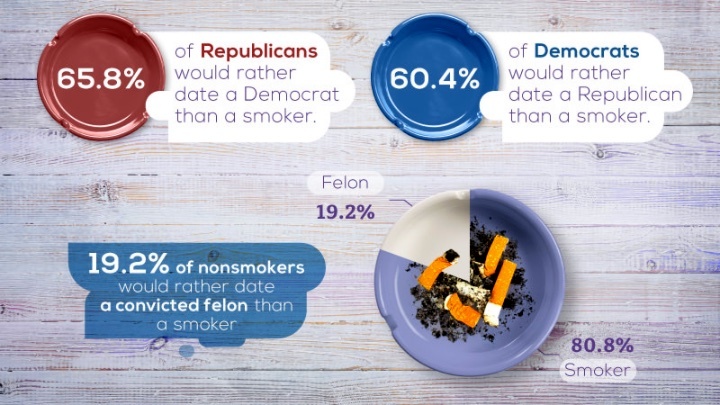

There’s a high social cost that comes with lighting up.

As part of Ipsos’ long-running studies on misperceptions, researchers asked people in Britain and the U.S. to guess how often people aged 18-29 in their country had sex in the past four weeks.

Couples who had fish more than 8 times a menstrual cycle had a 47% shorter time getting pregnant than those who didn’t, and had 22% more sex than those that didn’t.

A new study shows that some men’s reaction to sex is not what you’d expect, resulting in a condition previously observed in women.

While the gender gap is narrowing, women still do seven hours more housework per week than men (and that doesn’t include the child-caring).

A new study asserts that liberals and conservatives alike equally disdain hateful comments online, but only when they’re written by women.

A study of over 15,000 men and women reveals interesting data regarding what we claim.

On hallucinating a teensy Virgin Mary in a water fountain, our weird relationship to fame, her stint as an elf-hunting camp counselor, and more in what feels like a 4 am college conversation with the inimitable Parker Posey.

Not good news for inattentive married dudes.

Ever notice how people with conservative sexual attitudes seem to still cheat at the same rate as their more liberal peers? A new study says you’re onto something.

Psychologists figure out how men and women view engagement rings in light of how hot they think they are.

It’s been demonstrated that women are more attracted to men with attitudes of benevolent sexism. A new study asks why.

In her vivid, dreamlike new book of short stories, Florida is a humid, seething organism that wants to eat you. Snake-infested. Full of sinkholes. A thing to resist, get lost in, surrender to, and sometimes, temporarily escape.

A little kindness goes a long way. Not being mean goes longer.

Smart connected devices finding their way into million of’ homes are being taken over by domestic abusers, allowing them to invade and disrupt victims’ lives in a new, terrifying way

The online dating world has become more and more profitable as single people search for love.

The findings are among the few to detail the intersection of pathological personalities and sex preferences.

In a new study, people with a keener sense of smell reported finding their sexual activities more “pleasant”, and women with a greater sensitivity to odours had more orgasms during sex.

A new study shows how the personalities of men and women are changed by marriage.

It’s ironic that although we’re more connected than ever before, we’re lonelier than ever, too.

A study finds that re-conditioning married individuals by linking spouse photos to pictures of puppies and bunnies makes us like our mates more.

From what we know about the young prince and actress, how does the future look for their relationship based on psychological studies of successful marriages?

Here’s why the porn industry leads the way in developing virtual reality.

“Navigating sexual activity can be difficult, especially when partners’ behaviours that indicate their sexual interest are subtle.”

Older, wealthy men exploiting financially strapped young women isn’t new, but it’s an exploding phenomenon with the rising price of higher education and a factor in the ongoing HIV crisis in Africa.

Both younger and older siblings uniquely contribute to each others’ empathy development. rn

Though conventional wisdom suggests that birth order influences personality, newer research says this isn’t true. What is true is how powerful an effort to remain close to our brothers and sisters as we grow up can be.

Love is like umami. Adulthood is accepting the schmo you are. Wordplay and worldbuilding with novelist Meg Wolitzer.

File under: “What… you’re SURPRISED by these results?!”

A survey by SimplyHired examines the experiences and feelings of people who’ve had office affairs and people who haven’t.