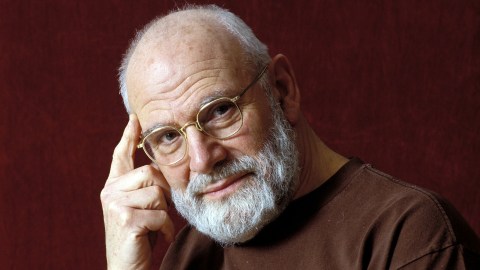

Want to write a book? Oliver Sacks and Susan Barry began theirs as letters

- Susan Barry began writing letters to Oliver Sacks in 2004, beginning a 10-year friendship that would last until the latter’s passing in 2015.

- Sacks once told Barry that his books started as letters to friends and colleagues.

- Barry describes how her letters to Sacks about two inspiring students led her to share their stories with the world.

In December 2004, I sent my first letter to Oliver Sacks describing a remarkable change in my vision. He was intrigued and wrote back right away. Thus, we began a ten-year correspondence involving over 150 letters; the last were exchanged three weeks before Oliver died.

“Most of my books have started out as letters to colleagues or friends […] and I think of the book as a ‘letter’ to everybody,” Oliver once wrote to me, and I found myself using my letters to Oliver in just this way. As I wrote, I worked out problems and fleshed out ideas, many of which ended up in my first book, Fixing My Gaze.

When I described to Oliver the experiences of two of my students, he found them fascinating and encouraged me to write their stories. Here is the first of those letters, written on Oct. 11, 2014:

Dear Oliver,

A few weeks ago, one of my students named P. bounded into my office with her ponytail bouncing behind her. “You look happy. You’re wearing your hair differently,” I said to her. P. is partially deaf and used to cover her ears with her hair to hide her hearing aids, but, on this day, her hair was pulled back, and I couldn’t see any hearing aids at all. When I asked her what happened to them, P. quickly reached up and removed a tiny object from inside one ear and then showed me how the parts of the aid that hung around her outer ear were transparent. When she put the hearing aid back in her ear, the external parts seemed to disappear. But the hearing aids had improved her life in more ways than just appearance.

“I love technology,” P. said. “My hearing aids keep improving. For the first time, I can tell where a sound comes from. I don’t have to do this” — and then she opened her eyes wide and moved her head back and forth as if to scan the scene in what was obviously a very practiced move. “When I hear a sound, I don’t have to look for it. I just know where the sound is coming from.”

I thought this was spectacular — that P. could develop a new skill, sound localization, shortly after acquiring better auditory input — auditory input that presumably allowed her to distinguish at which ear the sound first arrived.

One of my most inspiring students, Zohra Damji, did not hear at all until she received a cochlear implant at age twelve, an age considered quite old for learning to hear for the first time. One day, when Zohra came to my office to drop off an assignment, I asked her, somewhat hesitantly, if she would tell me her story. She was very anxious to do so.

We had many conversations together, and on April 19, 2010, I wrote to Oliver about them:

Dear Oliver,

Two days ago, I had a long conversation with my student Zohra, the student who has been profoundly deaf since birth but received a cochlear implant at age 12. When her implant was first turned on, she did not recognize a sound as a sound but rather as a terrifying, unpleasant, unnerving feeling. For the first few days, she had this same frightening sensation every time she put on the implant. Eventually, she said, she came to accept the feeling. Then she began to expect the sensations and to interpret some of them as meaningful sounds.

I was intrigued by her use of the word “accept,” because I think anyone who goes through a substantial perceptual improvement must learn to tolerate a certain amount of discomfort, uncertainty, and confusion. If one doesn’t have the support of doctors, therapists, family, and/or friends, then one may not allow the changes to occur. One optometrist recently told me of her patient, a young man with amblyopia, who undertook vision therapy but was afraid that he’d develop stereovision during school. While studying for his exams, he wouldn’t let himself see in this new way. Shortly after he left school for home and vacation, the world popped out for him in 3D.

Zohra told me that the first sounds she recognized were those of car motors and human speech, although it took her one to two months before she could distinguish male from female voices. You’ll like this: The first word she could recognize by sound was — BANANA! Initially, she discriminated words by the number of syllables and by their distinctiveness. There are not many other English words that sound like banana!

I asked her what sounds surprised her, and she mentioned that she didn’t expect that soft or compliant things, including paper, skin, and water, would make sounds. She was very surprised by the following:

- the sound of crinkling paper

- the sound of cutting paper with scissors

- the swishing sound of her clothes when she moves (initially very disturbing to her)

- the sound of her own, small body as she shifts her weight on a chair

- the sound of brushing her teeth

- the sound of a broom sweeping the floor

- the sound of water boiling

- the squeaking sound when she rubs her hand on a mirror

- the sound of chalk on a blackboard

- the sound of putting a key in a lock

- the sound of a pencil or pen when she writes on paper

- the helpful fact that you can learn that you’ve dropped something because it makes sound when it hits the floor

- the sound of scratching her own skin

- the sound of a bowling ball rolling toward the pins in a bowling alley

- the sound of water coming out of a faucet

Zohra often had to ask what these new sounds were and is still delighted by new auditory discoveries. Since she can’t wear her implant while bathing, I asked her if she had heard the sound of water going down a drain. She said she had not, so, twice, we filled up my office sink with water and listened as the water drained out. Zohra was intrigued and I was thrilled — I had introduced her to a new sound!

Zohra is captivated by echoes that make her voice sound different when she is in a large room versus a small, tiled bathroom. She recently noticed that her mother’s voice on the phone sounds different when her mother has a cold and that people’s voices sound odd when they first awaken. She was very surprised to learn that it’s harder to hear a voice if the person is far away. Perhaps there’s not a good analogy here with vision. If one has normal or corrected-to-normal acuity, distant objects don’t look blurry; they just look smaller. In contrast, distant sounds appear muffled.

When she hears laughter, she wants to laugh, too. She never had this feeling when she saw but could not hear a person laughing.

Susan Barry

The biggest surprise however was learning that she can hear the emotion in a person’s voice. She can hear anger, sadness, and laughter, and, most important, these sensations evoke a strong response in her. When she hears someone crying, she instantly feels sympathy but doesn’t usually want to cry herself. But when she hears laughter, she wants to laugh, too. She never had this feeling when she saw but could not hear a person laughing. She had no idea that sounds could have such large effects on her mood or that so much meaning, information, and emotion is conveyed through the rhythms and dynamics of speech.

As Zohra was speaking about this, there were some students chatting away in the hall just outside my office. Zohra could not understand their words but loved the sounds, the ebb and flow of emotions conveyed by their voices. It made her feel more connected and more loved. Babies, she reminded me, are comforted by soothing words even though they don’t understand them. People’s voices are usually soothing to her. She must have felt terribly isolated when she could not hear.

Now that she can understand speech and speak well herself, I asked Zohra if she thinks by talking to herself. She does not. She does not look at a written word and then hear it in her head. While she can imagine environmental sounds like car motors, word sounds are more ephemeral. One exception is the word “stop.” Once, after receiving her implant, she narrowly avoided being hit by a car when her mother yelled “Stop!” Zohra can now hear the word “Stop” in her head.

Zohra could not explain to me how she thinks. When she thinks about one of my lectures, for example, she recalls the meaning of the lesson but not my individual words. In Seeing Voices, you describe “inner speech” and quote Vygotsky as describing it as speech without words, as thinking in pure meaning. This is what Zohra describes. I am also reminded of my friend’s daughter, K., who lost her sight in her teens from retinitis pigmentosa. K. loves reading Braille and teaching me some of the letters. I asked her what she thinks when she feels, for example, the Braille letter A. Does she see the shape of an A in her head or imagine the way it feels? K. could not explain her perception.

With Oliver’s encouragement, I did write up Zohra’s story, incorporating it into my second book, which also included an account of a young man named Liam who gained sight at age fifteen. Just as Oliver often spent years communicating and visiting with his subjects, I spent an additional eleven years getting to know Zohra, Liam, and their families before publishing Coming to Our Senses: A Boy Who Learned to See, A Girl Who Learned to Hear, and How We All Discover the World.