A meeting of the greatest minds in science, philosophy, and literature

- How much can we know of the world? Are our dreams of complete knowledge realistic or are there limitations to how far we can get?

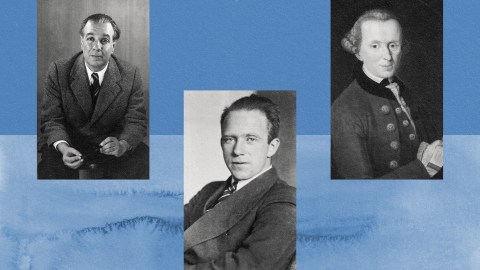

- A new book envisions an encounter of minds between the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, the physicist Werner Heisenberg, and the philosopher Immanuel Kant.

- The following is an interview of the author, Dr. William Egginton.

Dr. William Egginton is the Decker Professor in the Humanities and Director of the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute of the Johns Hopkins University. I spoke with him recently about his new book, The Rigor of Angels: Borges, Heisenberg, Kant, and the Ultimate Nature of Reality.

Marcelo Gleiser: Your book brings together three of the greatest Western minds from physics, literature, and philosophy, subjects that aren’t often presented together. There is a plan here, one that I am sure speaks to the very soul of this project. Can you elaborate on why these three, and how their fictional encounter illuminates your goals in writing this book?

William Egginton: This book is the fruit of several decades of reading, teaching, and thinking about the intersections between literature, philosophy, and physics. Obviously that trajectory encompassed so many more writers, thinkers, and scientists than these three. So when the time came to wrangle the project into a book, the question became: How to organize it? Who are the best characters through whom to tell this story, and how many should there be?

My first stabs at a structure were more expansive. I liked the idea of telling stories about specific human beings and distilling their insights out of those stories. But at first there were simply too many stories there — I believe I outlined a 12-chapter book with a different central character for each chapter — and the book felt scattered, even if the core intellectual project was the same. After that I reigned it in, but perhaps a little too much.

I sketched out what would have been a literary biography of one man. It was Boethius, believe it or not, who still plays a minor role in one of the chapters. But Boethius was too far away historically from some of the major innovations of 20th-century physics that I wanted to engage with. Then it hit me. Some years ago, I had published a little article on what would become the topic of the book in The New York Times. It had three central characters: [Jorge Luis] Borges, [Werner] Heisenberg, and [Immanuel] Kant. They had been there all the time! Returning to those specific figures I realized that among them, they had all the elements I needed.

The core idea was always to show how thinking deeply about a problem can lead to profound insights independently of the specific field of the thinker. In other words, “soft” humanistic approaches can enlighten “hard” scientific ones, and vice versa. In these three I believed I had found my proof of concept, since reading Borges, and then using Kant to think through some of the questions provoked by Borges, had over the years led me to a deeper understanding of what Heisenberg had actually discovered than had just reading Heisenberg and explanations of his discovery.

To be a bit more specific, Borges’ story about a man who becomes incapable of forgetting anything, incapable of any slippages or gaps in his perception of the world, when read through Kant’s analysis of the synthesis required for any experience in time and space to take place in the first place, lay bare in clarion (albeit non-mathematical) logic what Heisenberg had proven in his 1927 paper: An observation, say of a particle in motion, can’t ever achieve perfection because the very essence of an observation depends on there being a minimal difference between what is observed and what is observing.

It’s not about agency; it’s not about brain science; it’s a logical necessity built into the very nature of an observation. It wasn’t until the quantum revolution that the instruments became powerful enough for humanity to run into this limit. And it wasn’t until Heisenberg that anyone could put a number to it (even if Planck’s constant had been popping up for some time!), or, as he did, derive it as a fundamental principle.

Marcelo Gleiser: How does your book speak to the perplexities of being human, our existential angst of being aware of time’s passage and our mortality?

William Egginton: Part of what I wanted to keep at the forefront of the project is what you could call the existential dimension of what these thinkers were drawn to and what they discovered. “Existential” should here be understood in a quite specific way; precisely how [Jean-Paul] Sartre meant it when he glibly spoke of existentialism as reversing the traditional binary of essence and existence. Each of these thinkers — whether through storytelling, confronting philosophical shibboleths, or trying to use mathematics to explain experimental results — was inexorably drawn to what we could call a confrontation with existence.

In Borges’ case, this confrontation emerges as characters he creates explore some widely held presumption we tend to have about the world, push that presumption to its absolute limit, and then find that it fails them. In Kant’s, it came from his struggle with Humean skepticism, which wouldn’t allow him to rest on the rationalist certitude that we are able to know the world because our ideas and the world are of the same substance. In Heisenberg’s case, it shows in his willingness to cast aside anything but the observation itself, and insist, as he did to his dying day, that with science we seek not to explain nature itself, but “nature exposed to our method of questioning.”

What I then try to do in the book is follow how this realization manifests in their lives; what kind of consequence it must have had for people who took their art, their philosophy, and their science so seriously, to realize and hold true to the realization that we do not discover the world as it is but rather must create the very framework that allows us to understand it. Time, in such an understanding of the world, ceases to become a secondary effect, something that we can try to stave off, avoid. To avoid time would be to avoid the very condition of possibility of experiencing the world in the first place. We can only have the world because we can lose it, because we are losing it, every second of every day. Likewise, every choice we make involves the irrevocable loss of other possibilities. And those possibilities, those “roads not taken,” in your fellow New Hampshirite Robert Frost’s great poem, only exist because we have not taken them; they exist as and only as roads of regret.

Marcelo Gleiser: An underlying theme that seems to weave your narrative is the tension between our urge to know — of reaching some sort of “final” answer to our deepest questions about existence — and the impossibility of ever finding these answers. Are we to find some level of consolation in the very act of trying, or are we doomed to an existential dead-end?

William Egginton: Here I really think the least poetic of the three (well, okay, would that be Heisenberg or Kant? —well, here I mean Heisenberg) put it most powerfully. In his “1942 Manuscript” he wrote, “The ability of human beings to understand is without limit. About the ultimate things we cannot speak.”

I think Heisenberg was articulating here something about what I take to be the “internal” or “intrinsic” limitations of knowledge. The quest for knowledge cannot come to an end because our knowledge is intrinsically lacking. To know the world perfectly, in its totality, would be to have access to those “ultimate things” — it would be to stand outside of all existence, outside of time and space, the way that Augustine and the Neo-Platonists imagined God, as capable of grasping the Oneness of being in its entirety, its eternity. And obviously such a knowledge is absolutely, utterly incompatible with anything we can conceive of as human knowledge, which is precisely why our absolute inability to know absolutely, in this sense of “ultimate things,” is a wonderful, hopeful truth! It’s the very opposite of a dead-end because it’s the realization that by its very nature knowledge can never, ever meet such a dead-end.

Marcelo Gleiser: All three of your “characters” had to come to terms with loss. Love and loss, the loss of certainty and objectivity, the loss of a sort of platonic innocence related to the boundless powers of the mind. Loss seems to be an unavoidable part of being human, perhaps even a necessary one. Is loss, then, our greatest teacher of how to find meaning in life? If so, is it fair to say that your book is an optimistic take on the human condition, a guide to self-knowledge and growth?

William Egginton: It is very fair to say that. As I gestured above, their stories, philosophy, and science had existential implications, which each delved into in his own way. There can be no love without the ever-present possibility of loss; no truth without the foil of error and falsehood; no goodness without the possibility of choosing evil. While they labored in creating fiction, philosophy, and science, the unified implication of their work is a view of the world that demands our investment, our commitment, and ultimately our responsibility.

But unlike Sartre, for whom freedom was something we humans are condemned to, my take is, as you say, optimistic. For me, as someone who has learned at the feet of Borges, Kant, and Heisenberg, as well as many others who make appearances in this book, the truth that the rigor we find in the world is a rigor of chess masters, not of angels (as Borges so beautifully put it), still allows that it is a rigor, nonetheless. What we encounter when we study the world, when we deal with relations between us and other people, when we judge the beauty of a work of art — of course these are human perceptions, human codes, human values! But that doesn’t make them any less real, any less shared. In the philosophy I distill from these thinkers, neither AI nor neuroscience can take away one iota of our freedom to choose or our responsibility to each other and the planet — and I think that’s a good thing. In fact, I think it’s the only thing that can possibly save us.

Marcelo Gleiser: Every choice involves loss, the loss of what you have not chosen. Can you address the question of choice and free will in the light of your arguments?

William Egginton: One of the big philosophical discussions that the book opens up is how there can be free will in a mechanistic universe. The first thing to say here is that what I absolutely don’t advocate for is the idea that quantum uncertainty somehow leads to free will because it undermines determinism. Heisenberg correctly said that his discovery overturned Laplace’s demon, because at the quantum level it becomes impossible to know simultaneously the exact location and momentum of a particle, and hence the very presupposition of Laplace’s thought experiment ceases to hold. But the fact that mechanistic determinism is replaced by quantum indeterminacy doesn’t help save free will.

Rather, what I argue for in the book is a thoroughly compatibilist understanding of free will, one that was worked out by Kant but that has its roots in Neo-Platonist thought. We can fully embrace the idea that the human agent is a material entity in a material world ruled by the laws of physics, both quantum and classical, and at the same time find no contradiction at all in the notion that the human agent finds itself at a crossroads where it more or less freely, depending on the situation, chooses what to do. The fact that the choices take time and involve physical processes doesn’t make them any less free. The notion that they can’t be free because the trajectory of the deciding agent is knowable from beginning to end and hence somehow already decided for it is false, because it imports into a temporal spatial reality a presumption of non-temporal, non-spatial knowledge.

Early philosophers like Boethius could imagine a far more powerful foil to human freedom than mere neuroscience — namely an omniscient God — but were still able to see that God’s omniscience would easily coexist with human freedom, because God’s knowledge is outside of time and space and all human decisions take place inside time and space. So how much easier should it be to see that our extrapolations of knowledge about, say, neural processes are just as incapable of making serious arguments about an existential reality that we all live, all the time, namely, the obligation to choose.

Marcelo Gleiser: We tend to want to be sure, to be certain of everything we do, of the choices we make in life. But you are saying that this is not a realistic expectation. Why is uncertainty a good thing?

William Egginton: Because our presumptions of certainty lead to arrogance, to closed-mindedness, and to shutting down new avenues of thought. Science is about observing, experimenting, and coming up with provisional explanations. Those explanations are vetted by communities and, if they are upheld by evidence, accepted as the best explanation we have so far. But science doesn’t get where it’s gotten by deciding the game is up, that we have the ultimate solution and there’s no sense in thinking any more about this.

Yes, resources and time are limited, and obviously problems are put aside when a satisfactory solution has been obtained and seems to work to everyone’s satisfaction. But that is not the same as saying that a final, certain, and never-to-be-questioned answer has finally arisen. There always can come a time when a prior theory is upset by new evidence, and this is precisely how we continue to learn and grow as a species. In the end, this position is a version of what Socrates said in the Apology, that “what I do not know I do not think I know either.” Words justifiably held up as a kind of model of wisdom, and the kind of intellectual humility that should guide not only the scientific method, but how we go about judging the actions of others, and ourselves.