3 masterpiece books that told great stories through awful writing

- British novelist Martin Amis calls Don Quixote an unreadable masterpiece.

- David Foster Wallace thought American Psycho was badly written and manipulative.

- Virginia Woolf hated Ulysses, though her hatred may have been rooted in jealousy.

It’s difficult to say exactly what makes someone a good writer, but it’s even harder to say what makes someone a bad writer. “The literary world,” Emily Temple of Lithub notes, “can be a bit of an echo chamber (…) if enough people say a book is ‘great,’ it becomes official. It becomes a Great Book, and horrified looks are administered to anyone who would dare disparage it.”

Art criticism, like art itself, is inherently subjective, and opinions change as time goes on. A book that gets ignored while the author is still alive might be declared a masterpiece long after they die. Similarly, old books that strike us modern readers as archaic or inelegant in their writing would have probably made a completely different impression back when they were first published.

When judging the quality of a book, it is important to ask yourself whether or not you are being fair. The Russian writer Leo Tolstoy famously hated the work of William Shakespeare. However, while Tolstoy was convinced that Shakespeare’s work was objectively flawed, a close reading of his criticisms shows he was holding Shakespeare to the standards of an author rather than a playwright.

Even so, many readers concur that there are a number of books that are horribly written despite also being astounding works of literature. At first, this may seem paradoxical. After all, how can a book be good and bad at the same time? The answer is complicated, but essentially boils down to the fact that Literature with a capital L is about much more than syntax or narrative development.

Don Quixote: An unreadable masterpiece

A popular example of a good book with bad writing is Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, which follows a seemingly insane Spanish nobleman-turned-knight on a quest to prove that chivalry is still alive. Published in 1605, the writing of Don Quixote — its full title being The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha — is drawn-out and convoluted, even for the time.

The book has attracted its fair share of criticism over the centuries, including from British novelist Martin Amis. Although Amis credits Cervantes for having created an “impregnable masterpiece,” he also scorns the author for his “outright unreadability.” Reading Don Quixote, he writes in a collection of critical essays and reviews titled The War Against Cliché,

…can be compared to an indefinite visit from your most impossible senior relative, with all his pranks, dirty habits, unstoppable reminiscences, and terrible cronies. When the experience is over, and the old boy checks out at last (on page 846 – the prose wedged tight, with no breaks for dialogue), you will shed tears all right: not tears of relief but tears of pride. You made it, despite all that Don Quixote could do.

Not everyone agrees with this interpretation, though, and some choose to believe that the book’s unreadability is intentional, rather than a reflection of Cervantes’ shortcomings as a writer. The nonsensical plot and the endless digressions, they argue, are not supposed to be taken at face value but as parodies on the “vain and empty books of chivalry” with which Don Quixote himself is obsessed.

American Psycho: How bad writing manipulates

Writing doesn’t have to be outright unreadable in order to be bad. Sometimes, the underlying problems go deeper than sentence structure. In a 1993 interview with The Review of Contemporary Fiction, David Foster Wallace discusses his hostility against the writer Bret Easton Ellis, which he says is evoked “sometimes in the form of sentences that are syntactically not incorrect but still a real bitch to read.”

In the same interview, Wallace complains that Ellis tends to overwhelm his readers with unnecessary information, and that he goes to great lengths to create certain expectations only to subvert them later on. Wallace points to American Psycho, which “panders shamelessly to the audience’s sadism for a while, but by the end it’s clear that the sadism’s real object is the reader herself.”

The interviewer, Larry McCaffery, counters by suggesting that in writing American Psycho — about a Wall Street broker whose cutthroat environment pushes him into psychopathy — Ellis is being cruel to the reader not because he can but rather to make a point about people and the world. Wallace responds by saying that this is “the sort of cynicism that lets readers be manipulated by bad writing.” He continues:

Look, if the contemporary condition is hopelessly shitty, insipid, materialistic, emotionally retarded, sadomasochistic, and stupid, then I (or any writer) can get away with slapping together stories with characters who are stupid, vapid, emotionally retarded, which is easy, because these sorts of characters require no development. With descriptions that are simply lists of brand-name consumer products.

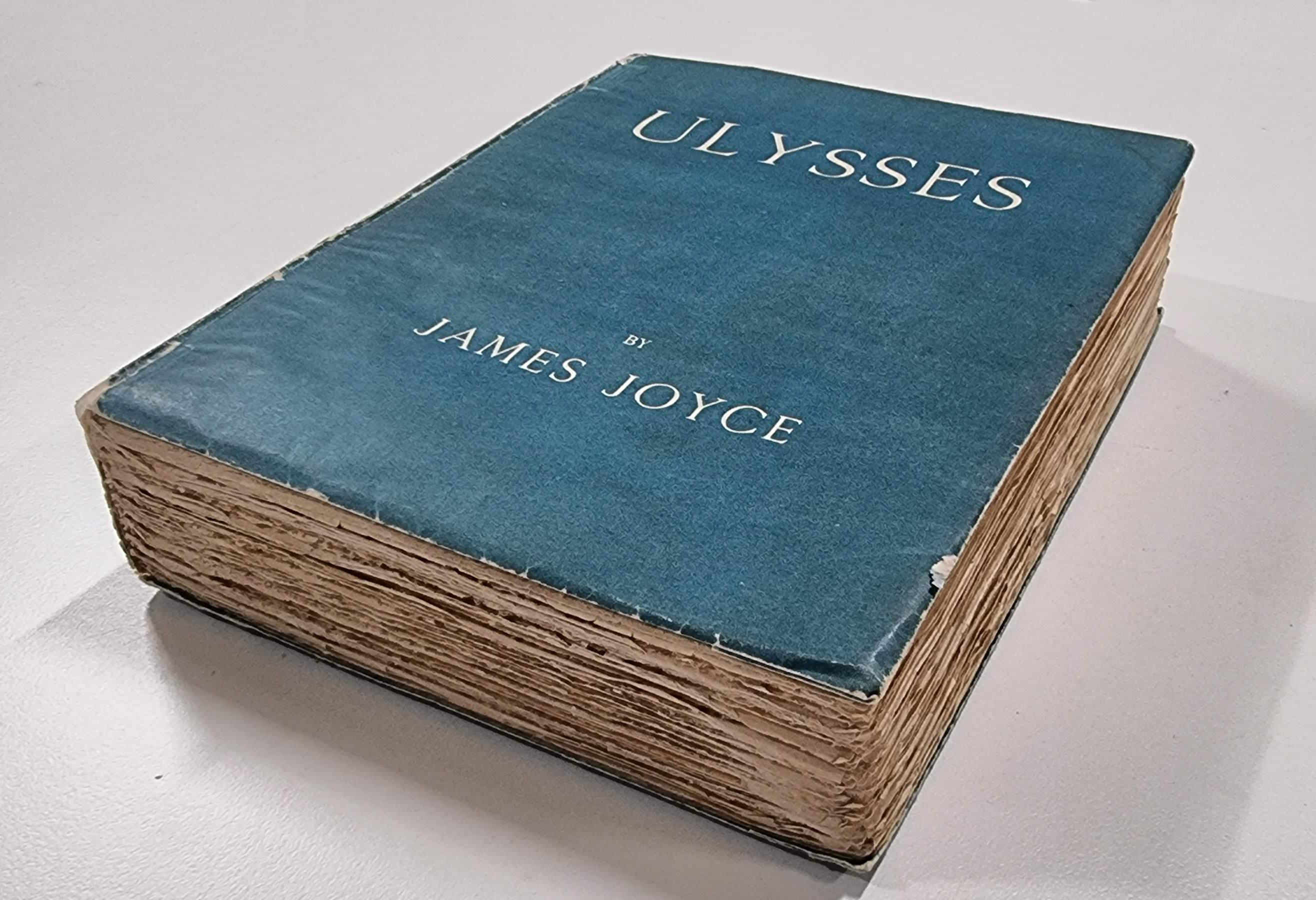

Ulysses: “Pretentious” and “underbred”

In the eyes of some readers, some supposed literary masterpieces are not just bad books, but bad books that are also badly written. Virginia Woolf, a pioneer of 20th century modernism, directed her fury at another pioneer of 20th century modernism: James Joyce. She specifically criticized his 1918 book Ulysses, which is about a man who makes an Odyssey-inspired journey through the streets of Dublin.

Even if you have never read Ulysses, you probably know that it was written in a stream-of-consciousness style that, while unusual at the start of the 20th century, has become omnipresent in more recent literature. Woolf was not a fan, and failed to see why others in her literary circle were. “Tom [T.S Eliot] thinks this is on par with War and Peace!” she complained in her diaries.

Her thoughts after finishing the book:

It is pretentious. It is underbred, not only in the obvious sense, but in the literary sense. A first rate writer, I mean, respects writing too much to be tricky; startling; doing stunts. I’m reminded all the time of some callow board school boy, full of wits and powers, but so self-conscious and egotistical that he loses his head (…) one hopes he’ll grow out of it; but as Joyce is 40 this scarcely seems likely…

Woolf’s dislike of Ulysses is somewhat puzzling, as her writing is likewise characterized by stream-of-consciousness prose, interior monologues, and fragmented narrative structures. James Heffernan, an English professor at Dartmouth College, has suggested that her criticism was based on a realization that Joyce, a rival, was “beating her at her own game.”

A matter of taste

Upon closer examination, Woolf’s evaluation of James Joyce does not appear to be all that different from Tolstoy’s evaluation of William Shakespeare. Both were frustrated by and jealous of the international success of other great writers in relation to their own, and both – albeit to a lesser extent – seem to have had different tastes that made them unable to appreciate the other’s work.

Neither Woolf nor Tolstoy appear to have been aware of their biases. If they were, they did not admit to it in their writing. The same cannot be said for Mark Twain. The creator of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn absolutely abhorred the writing of Jane Austen. But unlike other critics, he was able to recognize that his loathing was ridiculous and based mainly on personal preference.

“I haven’t any right to criticize books,” he explained in a letter from 1898, “and I don’t do it except when I hate them. I often want to criticize Jane Austen, but her books madden me so that I can’t conceal my frenzy from the reader; and therefore I have to stop every time I begin. Every time I read Pride and Prejudice I want to dig her up and beat her over the skull with her own shin-bone.”

He continues:

Whenever I take up Pride and Prejudice or Sense and Sensibility, I feel like a barkeeper entering the Kingdom of Heaven (…) I am quite sure I know what his sensations would be-and his private comments. He would be certain to curl his lip, as those ultra-good Presbyterians went filing self-complacently along. Because he considered himself better than they? Not at all. They would not be to his taste—that is all.