Researchers identify genes linked to severe repetitive behaviors

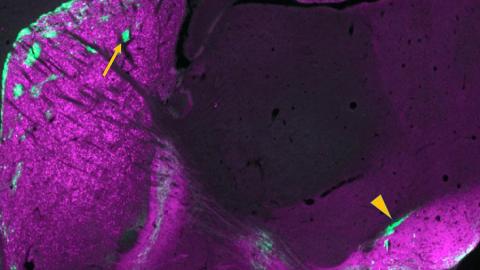

Image: Jill Crittenden

Extreme repetitive behaviors such as hand-flapping, body-rocking, skin-picking, and sniffing are common to a number of brain disorders including autism, schizophrenia, Huntington’s disease, and drug addiction.

These behaviors, termed stereotypies, are also apparent in animal models of drug addiction and autism.

In a new study published in the European Journal of Neuroscience, researchers at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research have identified genes that are activated in the brain prior to the initiation of these severe repetitive behaviors.

“Our lab has found a small set of genes that are regulated in relation to the development of stereotypic behaviors in an animal model of drug addiction,” says MIT Institute Professor Ann Graybiel, who is the senior author of the paper. “We were surprised and interested to see that one of these genes is a susceptibility gene for schizophrenia. This finding might help to understand the biological basis of repetitive, stereotypic behaviors as seen in a range of neurologic and neuropsychiatric disorders, and in otherwise ‘typical’ people under stress.”

A shared molecular pathway

In work led by Research Scientist Jill Crittenden, scientists in the Graybiel lab exposed mice to amphetamine, a psychomotor stimulant that drives hyperactivity and confined stereotypies in humans and in laboratory animals and that is used to model symptoms of schizophrenia.

They found that stimulant exposure that drives the most prolonged repetitive behaviors led to activation of genes regulated by Neuregulin 1, a signaling molecule that is important for a variety of cellular functions including neuronal development and plasticity. Neuregulin 1 gene mutations are risk factors for schizophrenia.

The new findings highlight a shared molecular and circuit pathway for stereotypies that are caused by drugs of abuse and in brain disorders, and have implications for why stimulant intoxication is a risk factor for the onset of schizophrenia.

“Experimental treatment with amphetamine has long been used in studies on rodents and other animals in tests to find better treatments for schizophrenia in humans, because there are some behavioral similarities across the two otherwise very different contexts,” explains Graybiel, who is also an investigator at the McGovern Institute and a professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT. “It was striking to find Neuregulin 1 — potentially one hint to shared mechanisms underlying some of these similarities.”

Drug exposure linked to repetitive behaviors

Although many studies have measured gene expression changes in animal models of drug addiction, this study is the first to evaluate genome-wide changes specifically associated with restricted repetitive behaviors.

Stereotypies are difficult to measure without labor-intensive direct observation, because they consist of fine movements and idiosyncratic behaviors. In this study, the authors administered amphetamine (or saline control) to mice and then measured with photobeam-breaks how much they ran around. The researchers identified prolonged periods when the mice were not running around (i.e., were potentially engaged in confined stereotypies), and then they videotaped the mice during these periods to observationally score the severity of restricted repetitive behaviors (e.g., sniffing or licking stereotypies).

They gave amphetamine to each mouse once a day for 21 days and found that, on average, mice showed very little stereotypy on the first day of drug exposure but that, by the seventh day of exposure, all of the mice showed a prolonged period of stereotypy that gradually became shorter and shorter over the subsequent two weeks.

“We were surprised to see the stereotypy diminishing after one week of treatment. We had actually planned a study based on our expectation that the repetitive behaviors would become more intense, but then we realized that this was an opportunity to look at what gene changes were unique to that day of high stereotypy,” says first author Jill Crittenden.

The authors compared gene expression changes in the brains of mice treated with amphetamine for one day, seven days, or 21 days. They hypothesized that the gene changes associated specifically with high-stereotypy-associated seven days of drug treatment were the most likely to underlie extreme repetitive behaviors and could identify risk-factor genes for such symptoms in disease.

A shared anatomical pathway

Previous work from the Graybiel lab has shown that stereotypy is directly correlated to circumscribed gene activation in the striatum, a forebrain region that is key for habit formation. In animals with the most intense stereotypy, most of the striatum does not show gene activation, but immediate early gene induction remains high in clusters of cells called striosomes. Striosomes have recently been shown to have powerful control over cells that release dopamine, a neuromodulator that is severely disrupted in drug addiction and in schizophrenia. Strikingly, striosomes contain high levels of Neuregulin 1.

“Our new data suggest that the upregulation of Neuregulin-responsive genes in animals with severely repetitive behaviors reflects gene changes in the striosomal neurons that control the release of dopamine,” Crittenden explains. “Dopamine can directly impact whether an animal repeats an action or explores new actions, so our study highlights a potential role for a striosomal circuit in controlling action-selection in health and in neuropsychiatric disease.”

Patterns of behavior and gene expression

Striatal gene expression levels were measured by sequencing messenger RNAs (mRNAs) in dissected brain tissue. mRNAs are read out from “active” genes to instruct protein-synthesis machinery in how to make the protein that corresponds to the gene’s sequence. Proteins are the main constituents of a cell, thereby controlling each cell’s function. The number of times a particular mRNA sequence is found reflects the frequency at which the gene was being read out at the time that the cellular material was collected.

To identify genes that were read out into mRNA before the period of prolonged stereotypy, the researchers collected brain tissue 20 minutes after amphetamine injection, which is about 30 minutes before peak stereotypy. They then identified which genes had significantly different levels of corresponding mRNAs in drug-treated mice than in mice treated with saline.

A wide variety of genes showed modest mRNA increases after the first amphetamine exposure, which induced mild hyperactivity and a range of behaviors such as walking, sniffing, and rearing in the mice.

By the seventh day of treatment, all of the mice were engaged for prolonged periods in one specific repetitive behavior, such as sniffing the wall. Likewise, there were fewer genes that were activated by the seventh day relative to the first treatment day, but they were strongly activated in all mice that received the stereotypy-inducing amphetamine treatment.

By the 21st day of treatment, the stereotypy behaviors were less intense, as was the gene upregulation — fewer genes were strongly activated, and more were repressed, relative to the other treatments. “It seemed that the mice had developed tolerance to the drug, both in terms of their behavioral response and in terms of their gene activation response,” says Crittenden.

“Trying to seek patterns of gene regulation starting with behavior is correlative work, and we did not prove ‘causality’ in this first small study,” explains Graybiel. “But we hope that the striking parallels between the scope and selectivity of the mRNA and behavioral changes that we detected will help in further work on the tremendously challenging goal of treating addiction.”

This work was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Saks-Kavanaugh Foundation, the Broderick Fund for Phytocannabinoid Research at MIT, the James and Pat Poitras Research Fund, The Simons Foundation, and The Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute.

Reprinted with permission of MIT News. Read the original article.