Meteorite’s fall to Earth retraced with dashcam footage

- In February 2020, a large meteorite blazed across the daytime sky over Slovenia.

- A team of astronomers was able to determine the trajectory of the meteorite by patching together footage from various cameras that happened to capture its descent.

- Meteorites are important to scientists because they offer clues about the origins of our solar system and the asteroids from which they fragmented.

On the morning of February 28, 2020, a fireball blazed across the daytime sky over southern Slovenia. It was an unusually large meteorite. Locals under its path reported hearing rumbling explosions. As far away as Croatia, Hungary, and Italy, people witnessed the space rock flare up against the blue sky as it broke into 18 pieces, leaving a trail of cosmic dust gleaming in the atmosphere.

It is normally easy for scientists to track large meteorites when they enter Earth’s atmosphere in the dark of night. For example, if the meteorite over Slovenia had fallen to Earth a few hours earlier, its descent would have been captured by one of the many nighttime fireball cameras that astronomers have deployed in the region to monitor incoming space rocks.

But this meteorite fell during the day. So, to recover the space rock and learn more about its origins, a team of astronomers had to develop an unconventional approach to trace where the meteorite flew through the sky and where its fragments likely landed.

Dashcam detectives

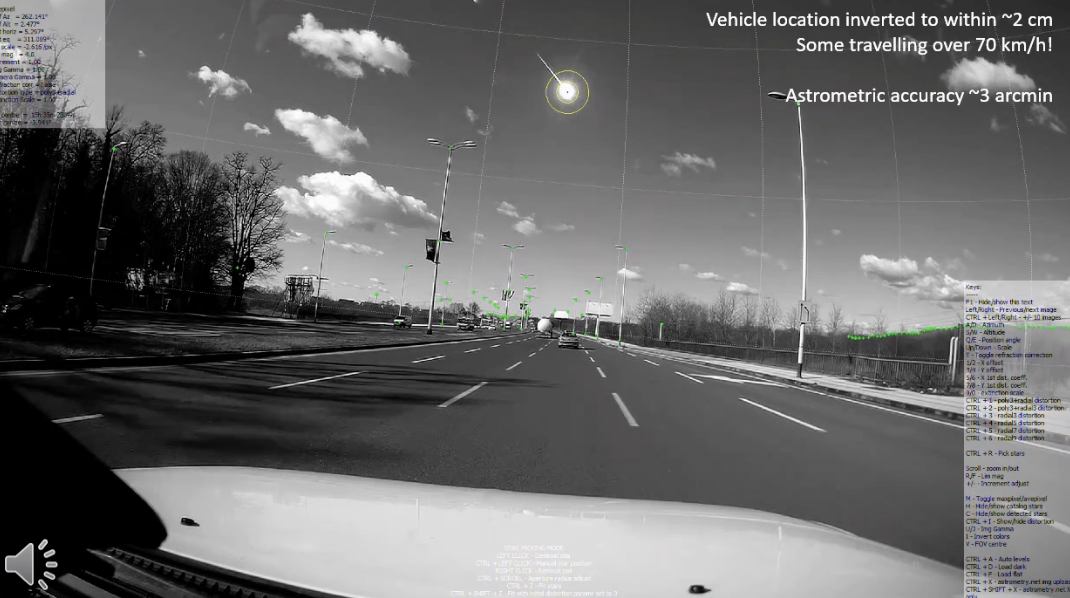

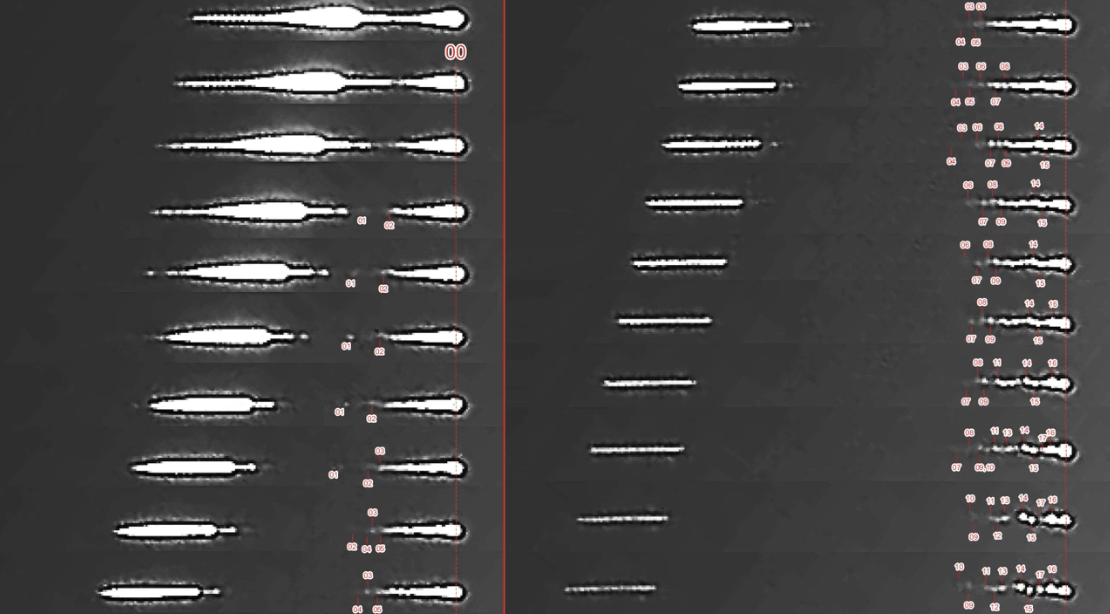

The meteorite’s descent to Earth happened to be captured by cameras situated on buildings, car dashboards, and a cyclist’s helmet. In a paper published by Copernicus, researchers described how they used landmark clues in these videos, along with other data, to triangulate the meteorite’s trajectory.

It was not easy. For example, some of the footage was captured by dashcams recording video as the cars were driving about 40 mph. This normally would not make things too difficult, considering that astronomers can pinpoint the position of space objects by comparing their movements and brightness to stars in the night sky.

But because it was daytime the researchers had to improvise. To determine the meteorite’s brightness — a measurement that offers clues about how meteorites fragment — the team bought the same type of dashcam that recorded the meteorite and then exposed it to a light source with a known brightness for comparison.

To narrow down the meteorite’s exact trajectory, the researchers asked locals in Slovenia to take photos of landmarks seen in the footage, such as buildings, mountains, and sign posts. Some of these photos included stars for reference. These images enabled the team to determine the exact locations of the cameras that captured the fireball and to correct for lens distortions in the dashcam footage.

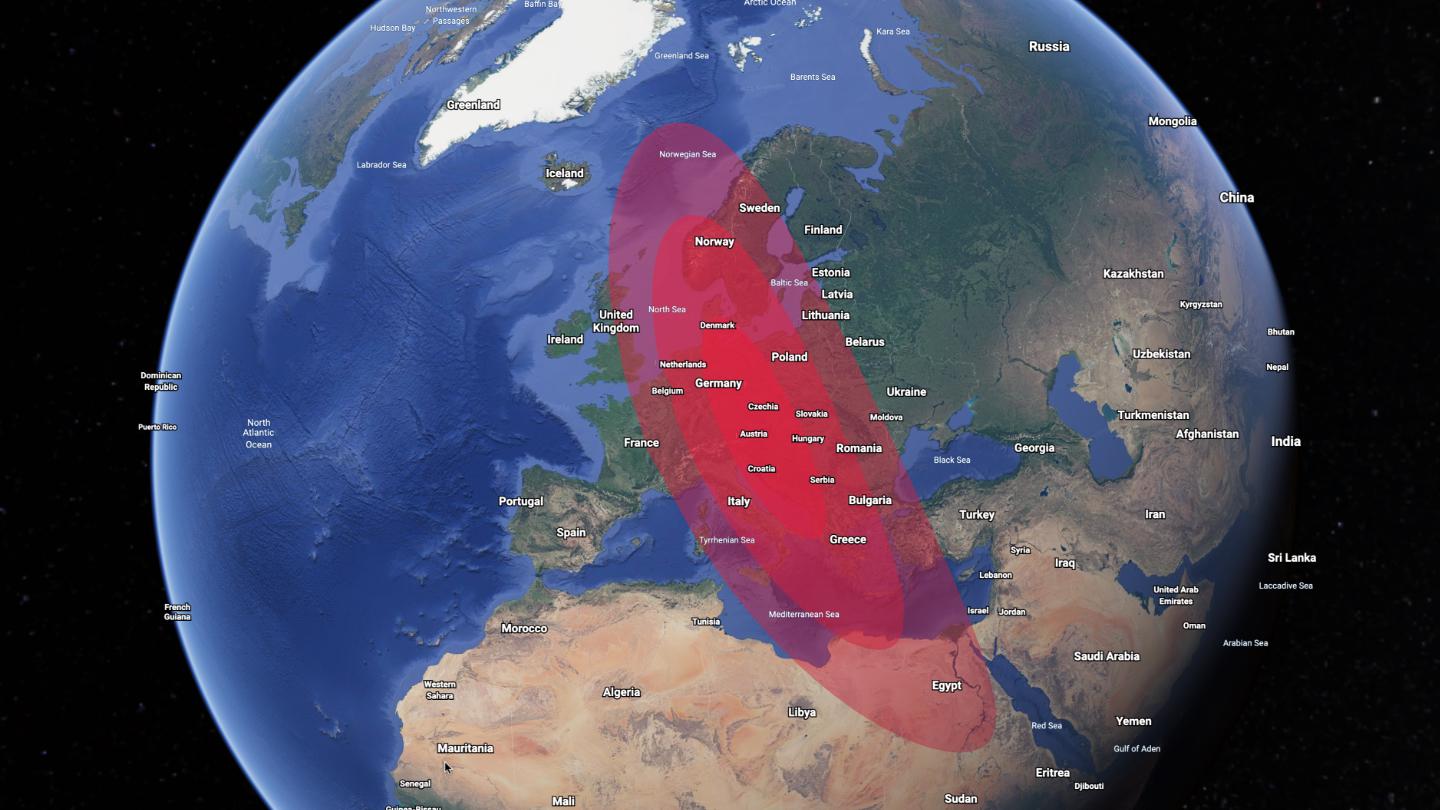

After combining the footage with data from other sources, such as seismographic recordings in the region, the researchers had a clearer picture of the meteorite and its trajectory. They calculated that it had an initial mass of about four tons as it entered Earth’s atmosphere. But once the meteorite reached an altitude of roughly 21 miles, it fragmented and lost about 90 percent of its mass.

The meteorite continued careening toward Earth, reaching speeds faster than three miles per second, before most of its fragments struck farmland in Novo Mesto, Slovenia. (Note: Space rocks are called meteoroids when they are still in space, meteors when they are burning in the atmosphere, and meteorites when they land on Earth.)

Over the following days, locals recovered three meteorite pieces, which were in pristine condition thanks to the quick recovery. However, the researchers suspect that the largest fragment — a piece with an estimated mass of 10 kilograms — has not yet been recovered.

“It probably fell into soft ground, as the predicted fall zone is over farmland, and it was thus plowed over before we had a good estimate of the fall location later in the year,” Denis Vida, lead study author and founder of the Global Meteor Network, said in a video presentation of the findings.

The researchers noted that their method could be replicated in future attempts to trace the trajectory of meteorites that fall during the daytime. Although future work would be better suited to determine exact origins of the Novo Mesto meteorite, they proposed it might have come from one of several asteroids: 2004 DF2, 2008 DK5, or 2005 OX, which NASA has designated as a “potentially hazardous asteroid” because of its close passes to Earth.

Why astronomers value space rocks

Meteorites are rare, making them valuable both to collectors, who sometimes pay $1,000 per gram of space rock, and the scientists who use them to study the cosmos and its origins. The unique blend of cosmic materials contained within meteorites can offer insights about the early conditions of our solar system, the composition of planetary building blocks, and the characteristics of the asteroids, or other space objects, of which the meteorites were once part.

The vast majority of meteorites discovered on Earth came from asteroids. But once in a while, people stumble upon meteorites that were once part of Mars or the moon, but then broke off from those objects during meteoroid impacts. Wherever their origins, most meteorites are small, ranging between the size of a pebble and an apple.

But some are massive. The Chicxulub impactor, for example, was the asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs after striking Earth about 66 million years ago, leaving behind an enormous crater 93 miles wide and 12 miles deep underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Catastrophic impacts like these are rare on Earth, occurring only a few times every billion years.

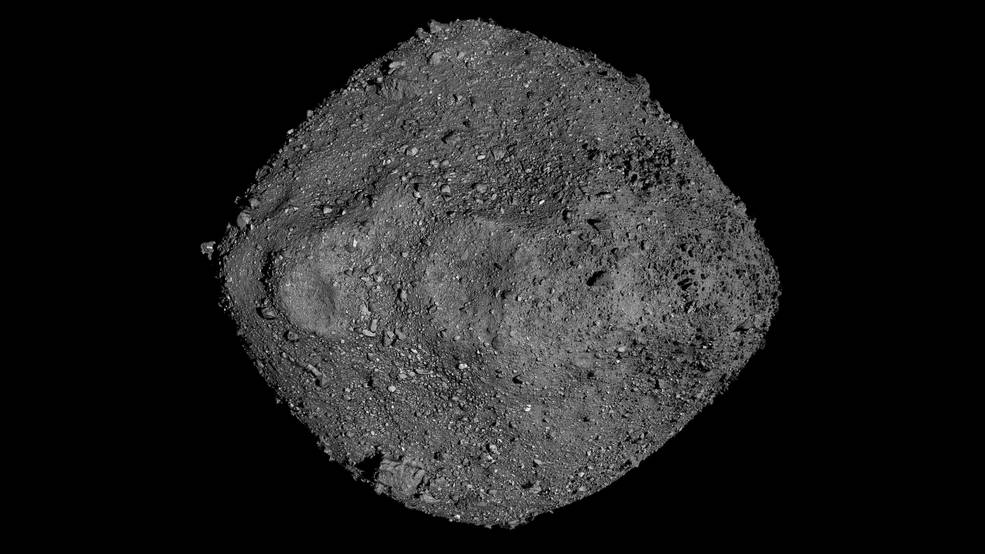

Scientists do not currently predict that Earth is at serious risk of any major impacts over the short term. But a study recently published in the journal Icarus examined the risks posed by Bennu, an asteroid that is about one-third of a mile in diameter and has spent hundreds of millions of years orbiting the sun. The results predicted that on September 24, 2182, Bennu has roughly a 1-in-2,700 chance of hitting Earth — about 13 times more likely than scoring four correct numbers on a Powerball lottery ticket.