Europa’s similarity to Greenland suggests its hidden ocean is close to surface

- Europa, thought to have a liquid ocean under a surface of ice, has long intrigued scientists.

- Previous estimates had suggested that the moon’s liquid ocean is trapped beneath an ice shell that’s approximately 20 to 30 kilometers thick.

- But a recent study, inspired by geological features observed in Greenland, proposes that the ice shell is not nearly as thick.

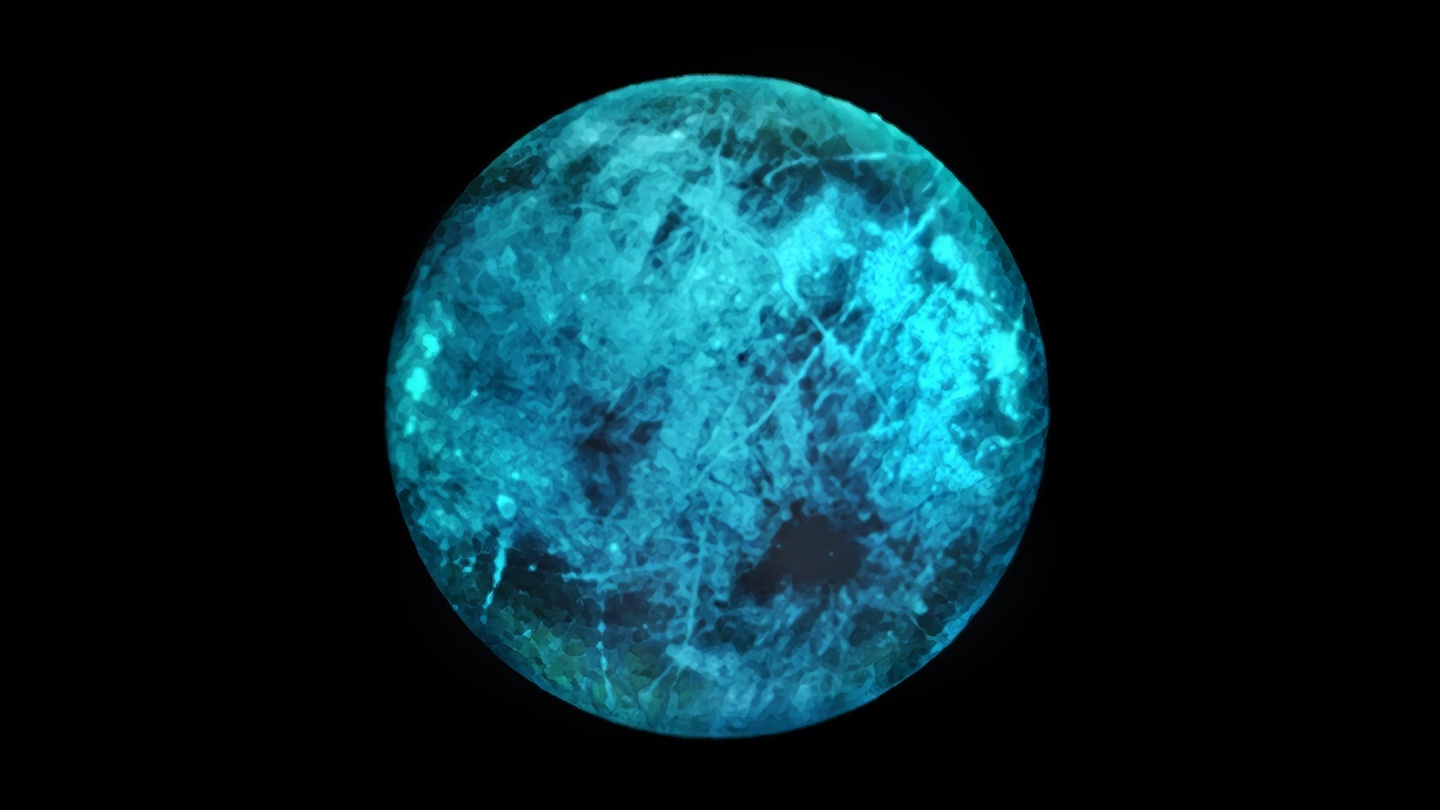

Of all the places in our solar system where extraterrestrial life seems possible, few excite people quite like Europa. The Galilean moon of Jupiter is known for its icy surface and subglacial ocean thought to contain liquid water — an environment in which some scientists speculate extraterrestrial life could thrive.

However, that supposed ocean has long been thought to be trapped under as much as 30 kilometers of solid ice, meaning that getting under it, or even seeing through it, is considerably difficult. But the results of recent study published in Nature Communications suggest that Europa’s ocean is much closer to us than previously thought.

Ice everywhere

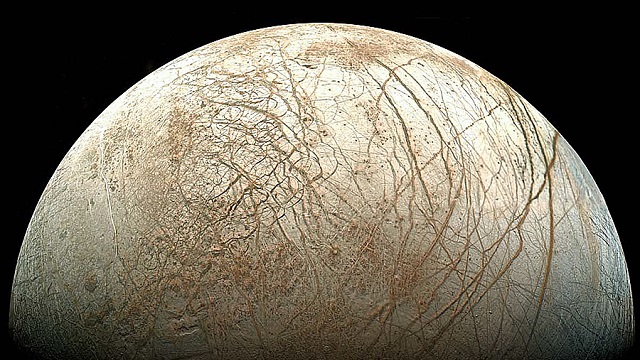

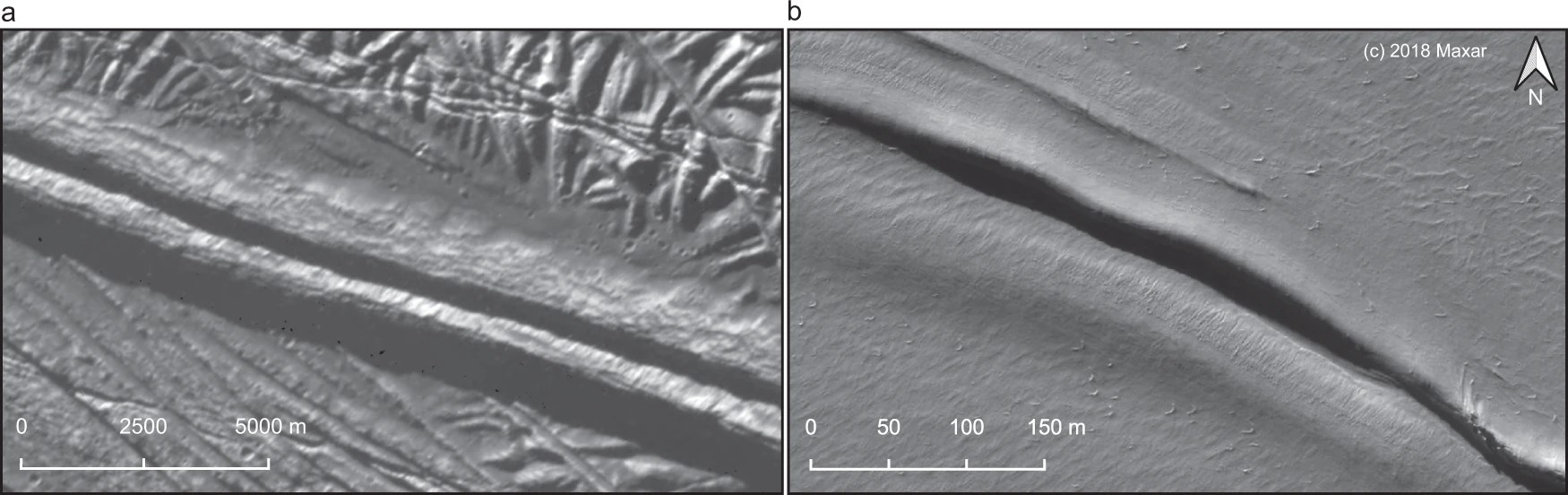

Existing models of Europa suggest that its young, geologically active surface is an ice shell that’s between 20 and 30 kilometers thick. This ice is far from smooth, with chaotic formations including bands, troughs, lenticulae, and ridges. Double ridges — a kind of “M” shaped crest seen across the planet — are particularly common, can stretch for hundreds of kilometers, and may be among the oldest features of the planet’s surface. It is believed they were formed in cycles across the moon’s history.

But exactly how they formed has remained an open question. Researchers have proposed various hypotheses, including cryovolcanism, in which volcanos spewing liquids below the freezing point; tidal forces; compression, and shear heating. Given the distances from here to Europa, even decades of knowing about these features and a considerable amount of high-tech equipment have failed to give a clear answer on what method is behind the features.

This is where an opportune picture from Greenland comes in.

The authors were working on a study of an ice sheet in Greenland when they happened to watch a presentation about Europa. They noticed that both Greenland and Europa have M-crests. Reasoning that these similar features likely have similar causes, the team proposed a formation mechanism.

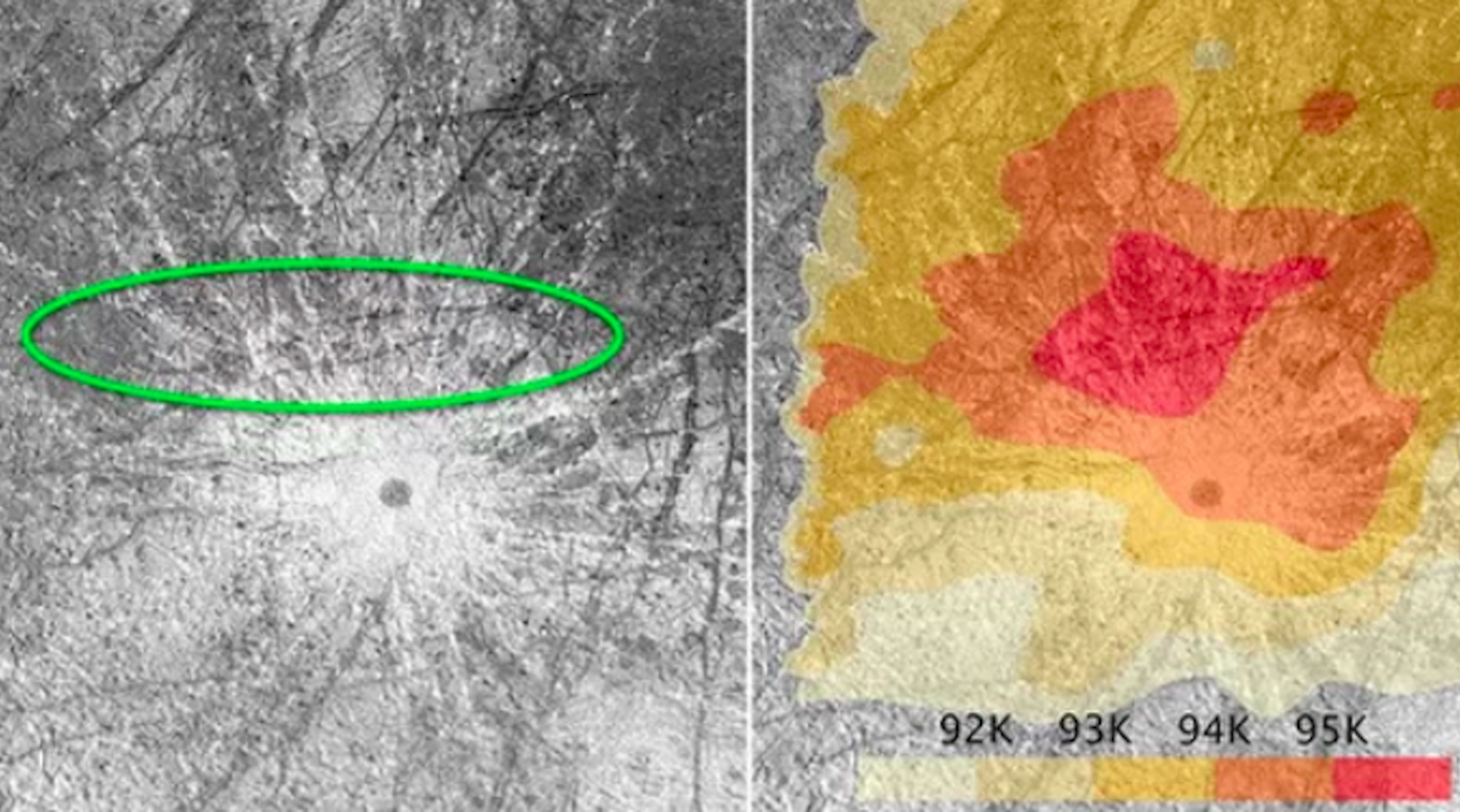

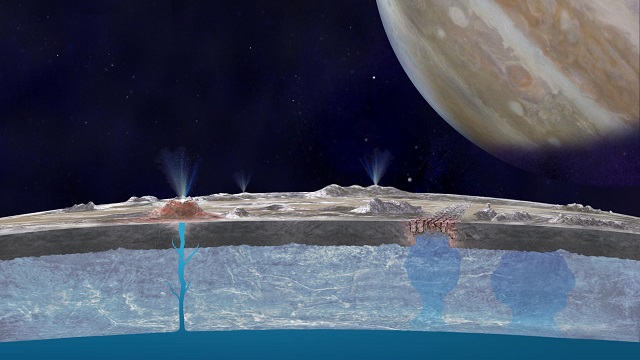

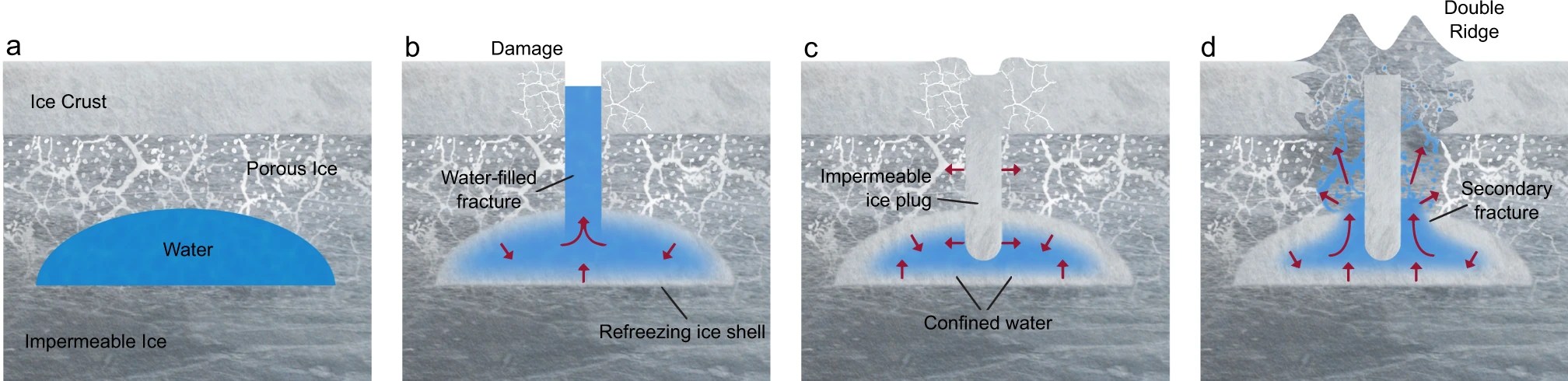

As seen in the image below, water is trapped below the solid ice crust under normal conditions. When damage occurs to the ice crust, either on Earth or Europa, the change in pressure within the trapped water causes some of it to move toward any fractures. When this refreezes, small peaks tend to form on the edges of where the water flowed. A proper double ridge can form as water continues to move toward the edges of the original crack, while pressure continues to settle.

Importantly, this also means that the water under Europa’s ice might be as close as 5 kilometers below the surface, at least in some places. As the researchers put it:

“If Europa’s double ridges also form in this way, it suggests that shallow water pockets must have been (or maybe still are) extremely common.”

The hypothesis could be tested by the Europa Clipper spacecraft, scheduled for launch in 2024 and for arrival at Europa in 2030. Current plans call for the craft to carry radar equipment that will be used to study the ice. If the researchers are correct, the ocean of Europa could be as close as a few kilometers from the surface, which would make getting to the water underneath much, much easier. It would also mean

Of course, the oceans of Europa would still be cold and difficult to access. But one win at a time.