Leonora Carrington: Last of the Surrealists

Surrealism never served its women well. Lee Miller basically seduced Man Ray to gain entry into what was predominantly a men’s club. Leonora Carrington met Max Ernst at a party. Ernst left his wife for the striking art student 25 years his junior and introduced her to Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, and Yves Tanguy. Joan Miró once asked Carrington to go out and pick her up some cigarettes. Carrington refused, unable to accept second-class status as a Surrealist. This past week Carrington passed away at the age of 94, the last of the legendary Surrealists and a reminder of how difficult it once was (and in many ways still is) for women to break into the ranks of art.

Carrington met Ernst in 1937. Within a year, Ernst ended his marriage and began living with Leonora. Ernst encouraged Carrington’s painting and writing. Around that time she painted her first significant Surrealist work, The Inn of the Dawn Horse (Self-Portrait) (shown above), which shows her at her most David Bowie-level androgynous reaching out to a hyena as a rocking horse looks on in the background. If that image makes little rational sense, then Carrington and Ernst’s life made even less as the Nazis began taking over Europe and the Surrealist circle came undone. First the French and then the Germans imprisoned Ernst. Carrington sought refuge in Spain, but suffered a nervous breakdown over the loss of Ernst. At the British Embassy in Madrid, Carrington threatened to assassinate Hitler himself and found herself institutionalized. Carrington later escaped, but she never saw Ernst again. (Ernst actually made it to America, where he met and later married Dorothea Tanning, another female Surrealist painter.) Carrington found freedom, love, and an atmosphere conducive to her art in Mexico.

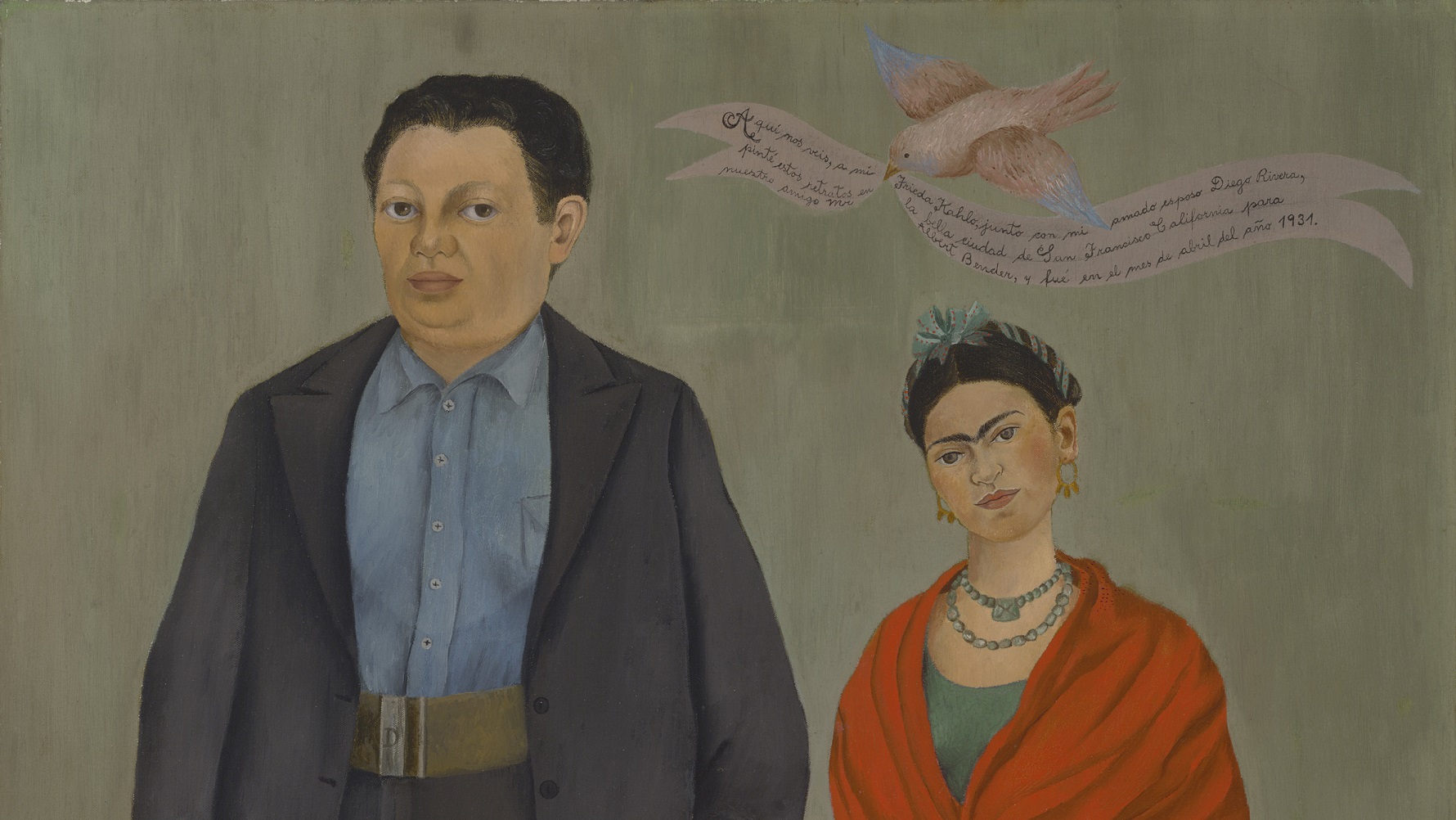

In Mexico, Carrington continued to incorporate arcane animal imagery into her art, but with the assistance of fellow female Surrealist Remedios Varo, added alchemy and the kabbalah to her repertoire. Leonora counted Frida Kahlo among her friends. Although Kahlo never accepted the Surrealist label, she may be the finest female Surrealist painter. What appeals the most in Carrington’s work is that Kahlo-esque quality of the personal intermixed with the irrational. Kahlo rose above “Mrs. Diego Rivera” status in the late 1970s as feminists found a heroine with a compelling personal story to match her talent. Carrington’s story, aided by her autobiographical writings, is just as compelling and her talent is unquestioned, but she’s never managed Frida-mania status. Perhaps in death Carrington will find the wider fame she lacked in a life that nearly spanned a century.

In the twentieth century, when modern art movements came and went with increasing frequency, the one constant always was a lack of women accepted into the inner circle. Those who did break through never lost the label of second-tier talents until the last few decades of art history reevaluations. Even then, figures such as Leonora Carrington could get lost in the shuffled deck of art history cards. Maybe Carrington outlived the male Surrealists to outlast them. The last of the Surrealists might still be among the first.

[Leonora Carrington (Mexican, born England, 1917). The Inn of the Dawn Horse (Self-Portrait), ca. 1937–1938. Oil on canvas; 25 5/8 x 32 in. (65 x 81.3 cm.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Pierre and Maria-Gaetana Matisse Collection, 2002 (2002.456.1). © 2004 Leonora Carrington/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.]