4 famous paintings that used to be controversial

- People from the past interpreted paintings differently from us.

- Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Édouard Manet’s Olympia were controversial because they questioned sexual taboos.

- Rembrandt van Rijn and Andy Warhol received backlash for pushing the definition of art itself.

“Talent hits a target no one else can hit; genius hits a target no one else can see.” This quote from philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer succinctly describes the fate of every forward-thinking individual. Talented people accept the conventions of their peers and beat them at their own game. The genius rejects convention in favor of uncharted territory. Because of this, they sometimes do not receive recognition until the rest of the world has caught up to their revolutionary visions.

The talent-genius dichotomy holds up in literature, where novels that are today regarded as classics were originally deemed failures. Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was ridiculed for its attempt to mimic dialect as well as its (for the time) positive portrayal of Black people. When the first copies of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby arrived in bookstores, critics insisted the Great American Novel would be forgotten in a decade. And the obscene language of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer pushed the boundaries of free speech.

This dichotomy applies to painting, too. Although paintings themselves remain constant, the ways we perceive them change over time. People from the near and distant past could have looked at the exact same art we now find in museums, but interpreted them in totally different ways. As such, studying the controversies that once surrounded famous paintings gives us an insight into how the social and political norms from various historical periods evolved to bring us to where we are today.

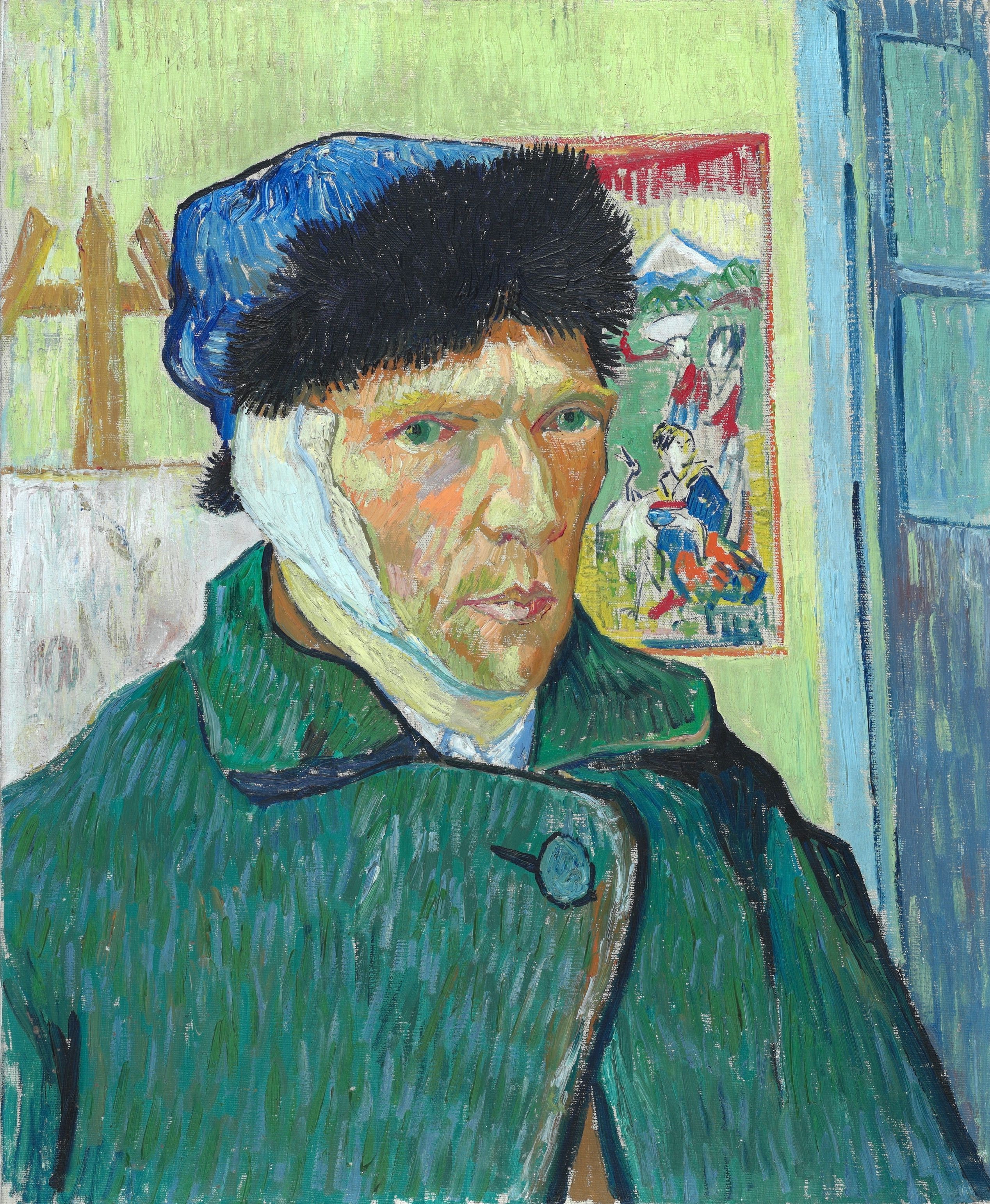

Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Night Watch

The Night Watch was commissioned in 1639 by Frans Banninck Cocq, a Dutch politician and captain of the Kloveniers. In the 17th century, cities like Amsterdam were not protected by standing armies but by civic militias that carried out nightly patrols. Cocq’s Kloveniers were one such group, and like others, they hired artists to paint portraits celebrating their dangerous but prideful volunteer work. These portraits were so common in the Netherlands that they qualified as their own genre: schutterstukken or “shooting portraits.”

Most paintings in this genre were straightforward portraits. Like modern-day students posing for their class photo, the militiamen dressed in uniform and filed into orderly rows. Flaunting this convention, Rembrandt van Rijn painted the Kloveniers in medias res as they were gearing up. He also added visual elements that, although seemingly unrelated to the group, were loaded with patriotic symbolism.

Legend has it that when The Night Watch was first shown in 1642, Rembrandt’s creative liberties were not appreciated. The painting’s action, while dynamic, made the Kloveniers look ill-prepared and disorganized. Its symbolism — including the shadow of Cocq’s hand cradling the sigil of Amsterdam embroidered on the coat of his lieutenant — didn’t absolve its stylistic unconventionality. Although scholars believe these criticisms were somewhat exaggerated in the retelling, they concede there must be some truth to them.

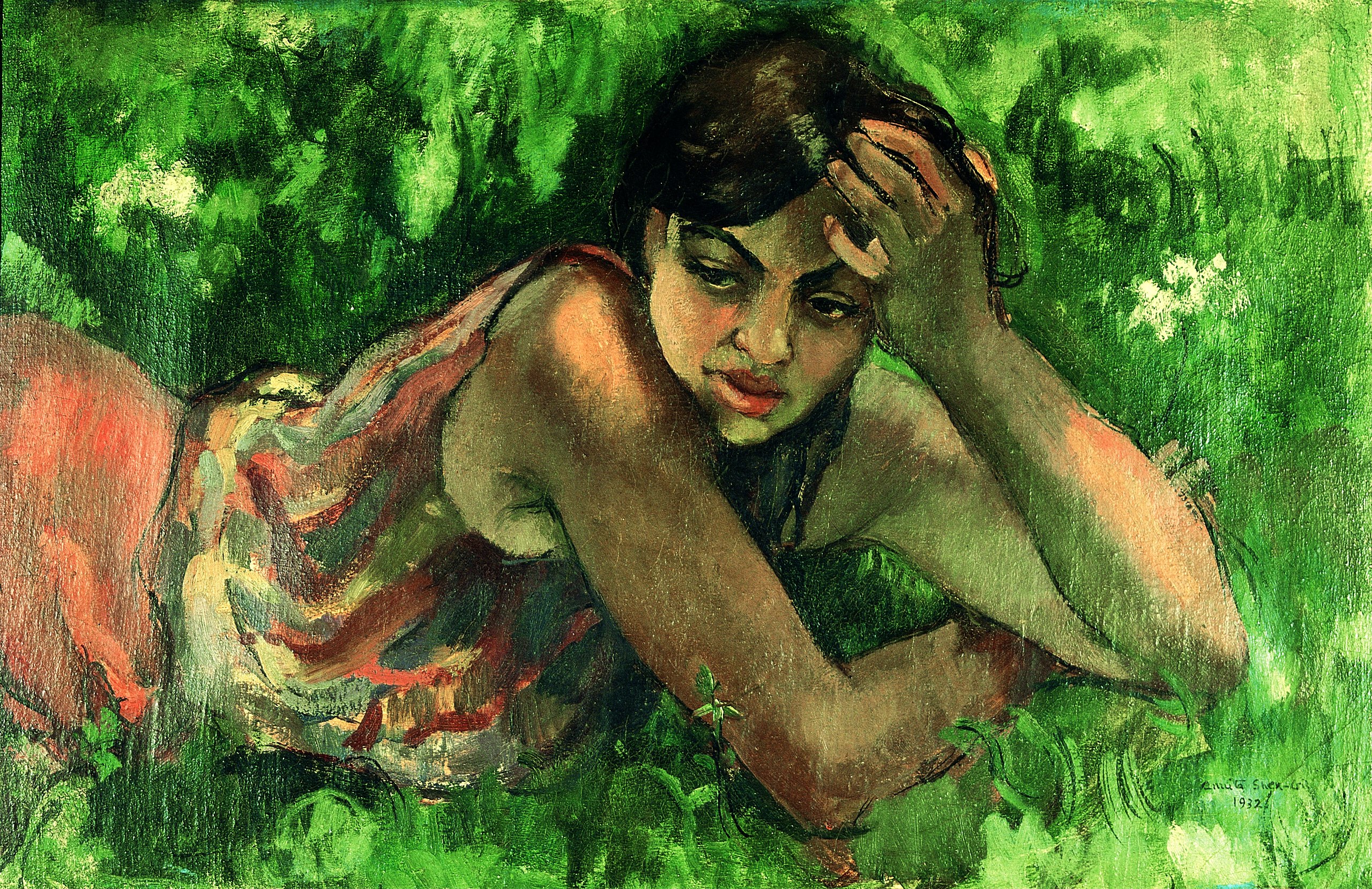

Édouard Manet’s Olympia

One of modern art’s pioneering troublemakers, Édouard Manet, made his biggest splash when he unveiled Olympia at the 1865 Paris Salon. The painting, which features a model reclining naked on a bed while a servant brings her a bouquet, was not shocking for its nudity. Naked bodies had been a staple of European art since the Renaissance. It was her identity. Manet had painted not a mythological figure, but a prostitute, one whose beauty was not just enchanting but sensual.

Olympia includes several visual clues that helped get this information across to Manet’s contemporaries. In 1860s Paris, the name “Olympia” was a euphemism for a sex worker. At the base of the bed rests a black cat, a symbol of promiscuity. In this context, the flowers are presumed to be a gift from one of the woman’s clients. Taking them, she looks directly at the viewer with a confident, unapologetic stare, identifying them as the next person who has come to see her.

In addition to breaking sexual taboos, Olympia angered the Salon with its evident allusions to Titian’s 1534 painting, Venus of Urbino, which suggested to the Parisian audience that Manet was mocking the celebrated Renaissance painter. While the gallery hired policemen to protect the painting from attackers, Manet nearly succumbed to the backlash he stirred up. “They are raining insults on me,” he wrote to his close friend the poet Charles Baudelaire. “Someone must be wrong.”

Titian’s Venus of Urbino

In Manet’s time, Venus of Urbino had become an emblem of high society, a work both refined and dignified. In Titian’s time, ironically, the painting generated as much controversy as Olympia. A depiction of the Roman goddess of love, desire, beauty, and femininity, it was tame by 19th-century French standards, but risqué by those of 16th-century Italy. Titian’s model, like Manet’s, looks directly at the viewer. Unlike Manet’s, she is accompanied not by a cat but a dog — a symbol of fidelity.

At a glance, Venus of Urbino appears no more scandalous than the classical statues that Renaissance artists praised and imitated. However, even in ancient Greece, female sexuality was a contentious subject. While Greek men were sculpted naked, Greek women often remained partially clothed. In medieval Europe, ruled by the Catholic Church, gender disparities deepened to the point that lesbianism wasn’t just any crime, but one so unspeakable that it could not be acknowledged in criminal records.

In retrospect, the most scandalous thing about Venus of Urbino is its possible origin. One prominent theory is that the painting was commissioned by Ippolito de’ Medici, a cardinal who served under his uncle, Pope Clement VII. The story goes that Ippolito approached Titian to paint a portrait of Angela del Moro, a Venetian courtesan he fancied. In one version of the story, it was Ippolito’s idea to depict her as Venus, without clothing. In another, it was Titian’s. Either way, it probably wasn’t Angela’s.

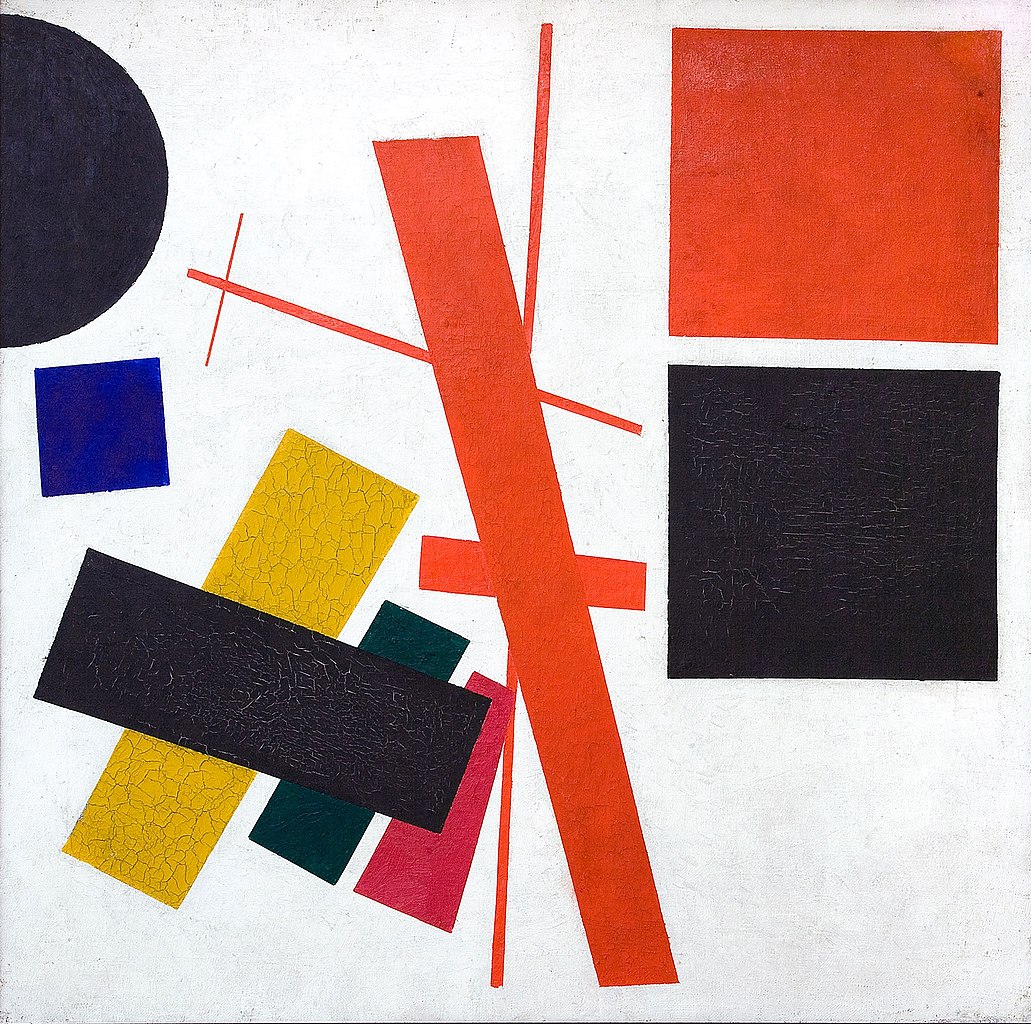

Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans

The history of modernism can be summarized as a series of increasingly unconventional artists challenging traditional notions about art. One of these artists, Kazimir Malevich, proclaimed art could be as simple as a black square. Another, Marcel Duchamp, said the same of a urinal. In 1961, Andy Warhol sought to pass off as fine art a series of hand-painted Campbell’s soup cans. They were even arranged as you would find them in the aisles of your local supermarket.

Not only did the public dislike Warhol’s exhibit (only 5 of the 23 soup paintings were sold and for a mere $100 each), but so did Campbell’s. The company sent a lawyer to hand the artist a cease-and-desist order. Warhol might have ended up in court were it not for the fact that the company’s next CEO, John T. Dorrance Jr., was an avid art collector who appreciated the creative concept as much as he recognized its commercial value. The paintings weren’t copyright infringement; they were free advertising.

A champion of pop art, Warhol sought to break down the barriers between art and life, which at this point in history had come to revolve around consumerism. Rembrandt and other artists from the Dutch Golden Age painted ordinary citizens; Warhol painted ordinary products. Before the Campbell’s project, he painted the canned Del Monte peaches he ate as a child, which he had an emotional connection to. After Campbell’s, on which he subsided as an impoverished artist, he moved on to Coca-Cola.