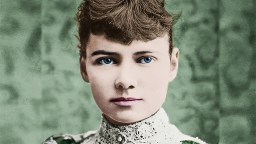

Gertrude Berg: The original media titan

If you’ve ever watched an episode of Friends or Seinfeld, you’ve seen the influence of the “second most influential woman next to Eleanor Roosevelt.” That woman, Gertrude Berg, dominated 30 years of radio and television by writing, producing, and starring in the hugely popular show, The Goldbergs. But who was she, how did she change the world, and how did the culture largely forget her genius?

Berg first rose to success in 1929 — the year of the stock market crashed and initiated the Great Depression — with the radio show The Rise of the Goldbergs. At a time when Jewish people were portrayed in the media as stereotypical immigrants, the show portrayed a relatable middle class family. At the head of the family was Molly Goldberg, a boisterous character who Berg would return to throughout her career. “It gets very confusing… I’m really Molly more hours of the day than I am Gertrude Berg,” she would say. The central message of the show was comforting to an anxious nation. You don’t need money to be happy, the show said, you can find everything you need inside your relationships with friends and family. As FDR is thought to have said: “I didn’t get us out the Depression, Molly Goldberg did.” And so the Goldbergs became American as apple pie knish.

Yoo-Hoo Mrs. Goldberg, a 2009 documentary by Aviva Kempner, gives a sense of how truly in-demand Berg was. The production schedule for The Goldbergs was gruelling, with Berg creating 5 new shows each week for 2 daily broadcasts. In one of the first high-profile cases of talent poaching, CBS swiped the show from NBC.

One factor that made The Goldbergs resonate was its ability to discuss topical issues. The radio show didn’t shy away from discussing war and Hitler in a very direct way. When World War II broke out, she used her enormous influence to convince her audience to buy war bonds and do their part, as she did, in the war effort. “Indifference is the greatest sin in the world,” she said on the show (a recording of this is in Kempner’s film). It was, however, her moral insistence that would cause her career to falter years later.

Berg became a titan during World War II. She wasn’t just writing, producing, and starring in her own radio show; she also realized how to capitalize on that success. Before Oprah or Martha Stewart, Berg built an empire around her name. There were jigsaw puzzles, comic strips, a newspaper column, a line of house dresses, two vaudeville shows, and a cookbook. It seems no one had the ear of the American people like Gertrude Berg.

In 1948, Berg saw a test for a new medium called television. Ever the forward-thinker, she wrote a teleplay (before there was a name for such things) and pitched it to the networks. They turned her down. Berg was incredulous. Kempner’s film details how she met with CBS head William S. Paley, pointing out to him that she carried his network through the Great Depression and a world war. She insisted that giving her a television show was the least Paley could do. Recognizing her financial and creative contributions, and after auditioning her in front of sponsors, Paley green-lit the show.

The Goldbergs debuted on CBS a year later. As the first domestic sitcom, Berg invented, crafted, and honed a genre that has never wavered in popularity. Most television shows that are set in an apartment or house still use some of the rules that Berg created. It is her we have to thank for the trope of neighbors who just walk in without knocking, character catchphrases, or moments of direct address to the camera. She is also who you can blame, or thank, for product placement, as every episode began with Berg talking out her window to the camera and selling Sanka coffee. No one had done that before, but if you’ve had the experience of watching a show and seeing your favorite character rave about a Ford Fusion, then you know this is still in play today.

While she was warm and loyal to her actors, she was not afraid to throw a fit in the name of perfection, frequently to the consternation of studio heads. But in 1951 she won the first ever Emmy Award for Best Actress. Kempner said, “She was a feminist before there was feminism… I think because the industry was so young, women could make it. She was successful right away and didn’t have to contend with the sexism of today.”

As the show enjoyed popularity, so-called Red Channels pamphlet was released, listing radio and television artists accused of Communist activities. Philip Loeb, the actor playing Molly’s husband Jake, was on the list (though not a Communist). Frightened at the prospect of lost advertising dollars, sponsors of the show threatened to leave if Berg didn’t fire Loeb. Berg refused. She stood up to CBS, and their sponsor General Foods, and as a result, CBS canceled the show.

But Berg did not give up. Taking a cue from Molly Goldberg’s proclivity to “save the day,” Berg was ready to try anything to save the show — and the fate of her friend. She knew that Cardinal Spellman in New York had some gotten some people removed from the blacklist, including Lena Horne and Harry Belafonte so they could sing on The Ed Sullivan Show. Cardinal Spellman did offer to help her, if Berg converted to Catholicism. She did not oblige. Loeb, still blacklisted and unable to find work, ended his own life.

The Goldbergs went off the air and I Love Lucy took its timeslot. Though Lucy could not have existed without The Goldbergs, modern audiences more easily recall Lucille Ball than Gertrude Berg. With the difficult economic times of the Great Depression and World War II behind them, audiences wanted Ozzie and Harriet and Leave it to Beaver, idealized versions of the new American Dream.

Though The Goldbergs returned to TV in 1952, after a year and half hiatus, the show was never the same. Ratings failed to increase after the setting was moved to the Long Island suburbs and the show was cancelled again in 1955. For the first time in almost 30 years, there was no Molly Goldberg or Gertrude Berg on television or radio.

True to the era, Berg was named as a Communist sympathizer by a prominent watchdog group. The incident cast a long shadow on her career. Formally the biggest star in the country, Berg could no longer work in the industry she revolutionized. But in typical Berg style, she went to the stage and conquered Broadway, in both dramatic and comedic roles, winning a Tony.

As McCarthyism faded, Berg worked the television variety show circuit.

In 1966, Berg died from heart failure at age 67. Without her trail blazing work, the path would have been much more difficult for women who wrote, produced and starred in their own shows. Women such as Lucille Ball (I Love Lucy), Marlo Thomas (That Girl), Mary Tyler Moore (The Mary Tyler Moore Show), Carol Burnett (The Carol Burnett Show), Roseanne Barr (Roseanne), Tina Fey (30 Rock) and Lena Dunham (Girls). Gertrude Berg might not be a household name like it once was, but as long as there are stories told on a small screen, her influence will be felt. As a writer, comedian, lady-person, and devout television watcher, I thank you, Gertrude. You’re a doll, truly. L’Chayim.

Gertrude Berg on the popular What’s My Line? in 1961.Big Think is proud to partner with the 92nd Street Y’s 7 Days of Genius Festival to bring you an in-depth look at the many qualities and characteristics of genius.