Society Painter: Otto Dix at the Neue Galerie New York

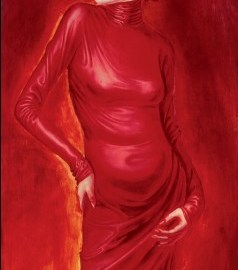

“When I tell people I would like to paint them, I already have their portrait in mind,” German artist Otto Dix once said. “I don’t paint people who don’t interest me.” Even more interesting than the people Dix painted is how he painted them. Dix’s 1925 Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber (pictured) gives a clue to how he saw the people of the Weimar era in Germany between the wars as the embodiment of the opulence and the decadence of the time. The garish red of the dress hugging the dancer’s form bleeds with the intensity of the period, which throbbed with the aftershocks of the Great War that scarred both Germany and Dix himself, who served on the front lines. An exhibition of Dix’s work currently at the Neue Galerie—the first exhibition ever of his work in North America—presents this complex and challenging artist of the past as someone who perhaps has something to say about our time.

Olaf Peters describes Dix’s “intransigent realism” in the catalogue to the show. In the 1920s, Dix’s work found a welcoming audience in America as the most representative artist of the Weimar. The difficulty of Dix’s brand of realism, however, hindered his ability to find a lasting place. Dix “decided to pursue a radical verism and a post-Expressionist Neue Sachlichkeit,” Peters argues, and “chose a form of modern painting that was decidedly focused on society” that “operated within the tension between art historical tradition, the avant-garde, new visual media, and aesthetic and philosophical discourses that transcended genres.” All of these forces coalesce in images such as Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber, which unsettles us on so many levels—aesthetically, morally, philosophically, sexually. While Picasso, Duchamp, and others kept the spotlight on themselves through their art, Dix never flinched from his primary goal of illuminating the world as he saw it, and felt others should see it.

Looking at Dix’s work can make even the hardest heart flinch. The honesty of the brutality of his wartime work sears your consciousness like the very best work of Goya. Dietrich Schubert analyzes Dix’s self-portraits of the war years as a response to the dehumanization, sometimes the literal erasure by destruction of the faces of others. These self-portraits reflect Dix’s psychological digestion of the events around him. They became the coping mechanism in which he preserved his own ego while also documenting the stages of grief faced by someone in the macabre theater of war. Dix’s images seem startling relevant today as touchstones for the understanding the violence of the War on Terror we face today. You look and wonder what Dix would make of Abu Ghraib and other tragedies we’ve yet to face entirely or honestly.

As the preeminent showplace of modern German art in America, the Neue Galerie continues through Otto Dix its mission of bringing the greatest German artists to America not as curiosities but as illuminating and relevant prisms through which we can view our present condition. The long gap between the early embrace of Dix in America and this present exhibition deprived us of an artist with much to say about the American love of waging war and its toll on our collective soul. Dix’s warning from history seems hopeless only to those who refuse to see the hopefulness of his honesty. Only someone who thinks things can get better is willing to show us the very worst. Dix allows us to look at the very worst in ourselves and our times and imagine a better world.

[Image: Otto Dix (1891-1969), Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber, 1925. Oil and tempera on plywood. 120.4 x 64.9 cm (47 3/8 x 25 1/2 in.). Sammlung Landesbank Baden-Württemberg im Kunstmuseum, Stuttgart. © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG, Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy of the Neue Galerie New York.]

[Many thanks to the Neue Galerie for providing me with the image above and for a review copy of the catalogue to Otto Dix, which runs through August 30.]