The most famous logic puzzle from the best police comedy on television, and how to (finally) solve it! “I have made the most important discovery of my career, the most […]

Search Results

You searched for: color

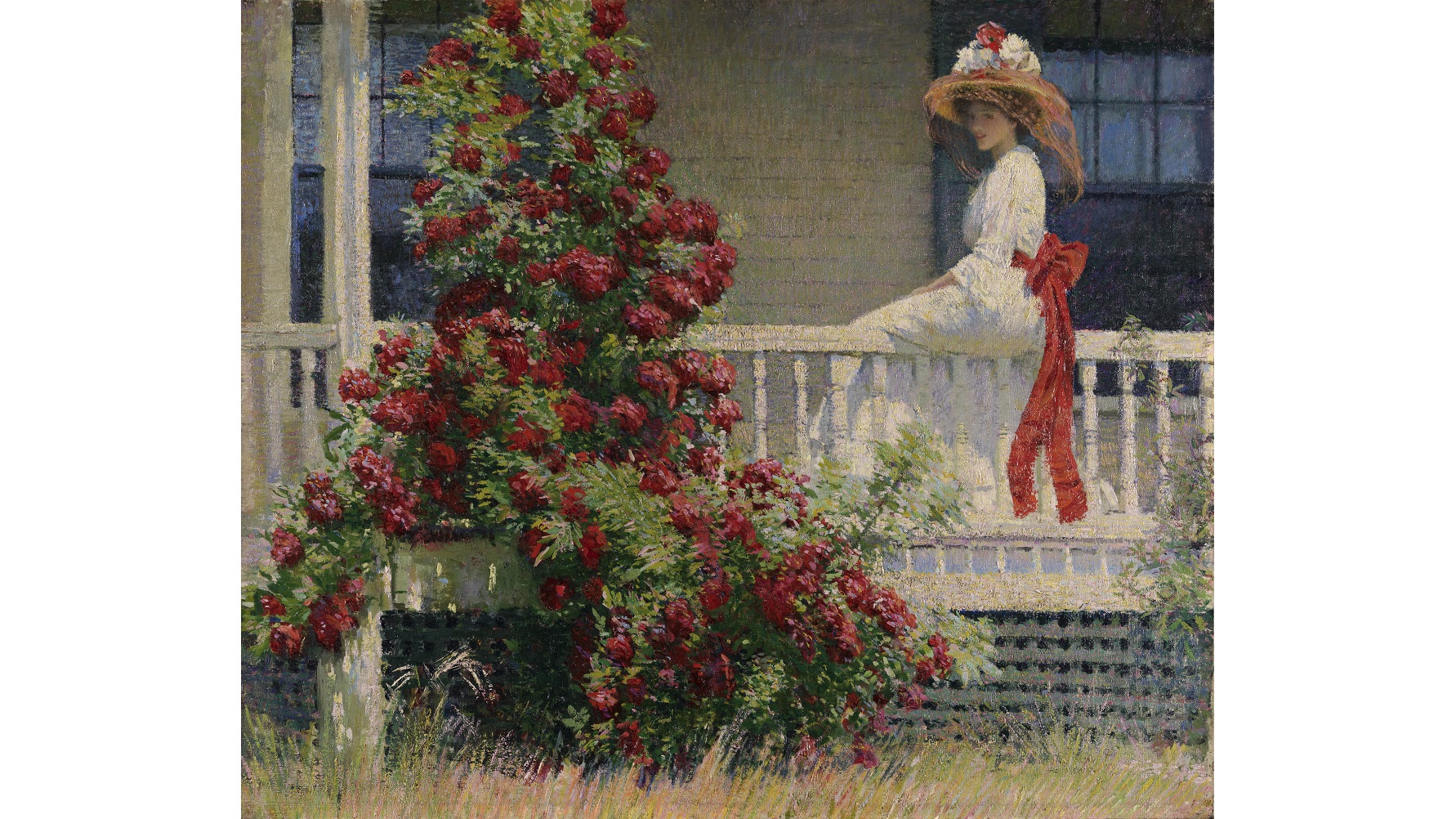

American Impressionism’s often been seen as a pale copy of the French Impressionism that flowered in the late 19th century. Although American Impressionists early on copied their French counterparts (and even made pilgrimages to Monet’s Giverny garden and home), the exhibition The Artist’s Garden: American Impressionism and the Garden Movement, 1887–1920, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts through May 24, 2015, proves that American Impressionism quickly blossomed into something distinct—and distinctly American—by the turn of the 20th century. Capturing aesthetically a moment of contradictions as American nativism threatened to close borders while women’s suffrage struggled to open doors, The Artist’s Garden demonstrates the power of flowers to speak volumes about the American past, and present.

Obesity is one the rise, and telling people to just eat less isn’t enough to stop it. One study thinks it has found a way to curb men’s appetites by simply changing the lighting in the room.

After the CMB, before the first stars, there was nothing to see. Or was there? “[I]f there were no light in the universe and therefore no creatures with eyes, we […]

Spin a roulette wheel a million times, and you’ll see a fairly even split between black and red. But spin it a few dozen times, and there might be “streaks” of one or the other. The gambler’s fallacy leads bettors to believe that they odds are better if they bet against the streak. But the wheel has no memory of previous spins; for each round, leaving aside those pesky green zeroes, the odds for each color are always going to be 50-50.

Using Experimental Philosophy to Shift Perspective, with Jonathon Keats Jonathon Keats introduces his workshop by listing the following five rules for looking at the world like an experimental philosopher: 1. […]

The most important lessons about Earth come from looking outward. “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.” […]

How often does a CEO directly and publicly address organizational politics? How many compose a list of the worst forms or could even identify them?

On March 4th at 19:30:15 Universal Time, Venus and Uranus will pass within 0.1° of each other. Here’s how to see it. “Since you cannot do good to all, you […]

Joy Division’s iconic “soundscape” was designed by a Cornell University astronomer.

And why do some of them appear to be right here in our own galaxy, which formed much later? Image credit: DSS, of SMSS J031300.36–670839.3, candidate for “oldest star.” “Let […]

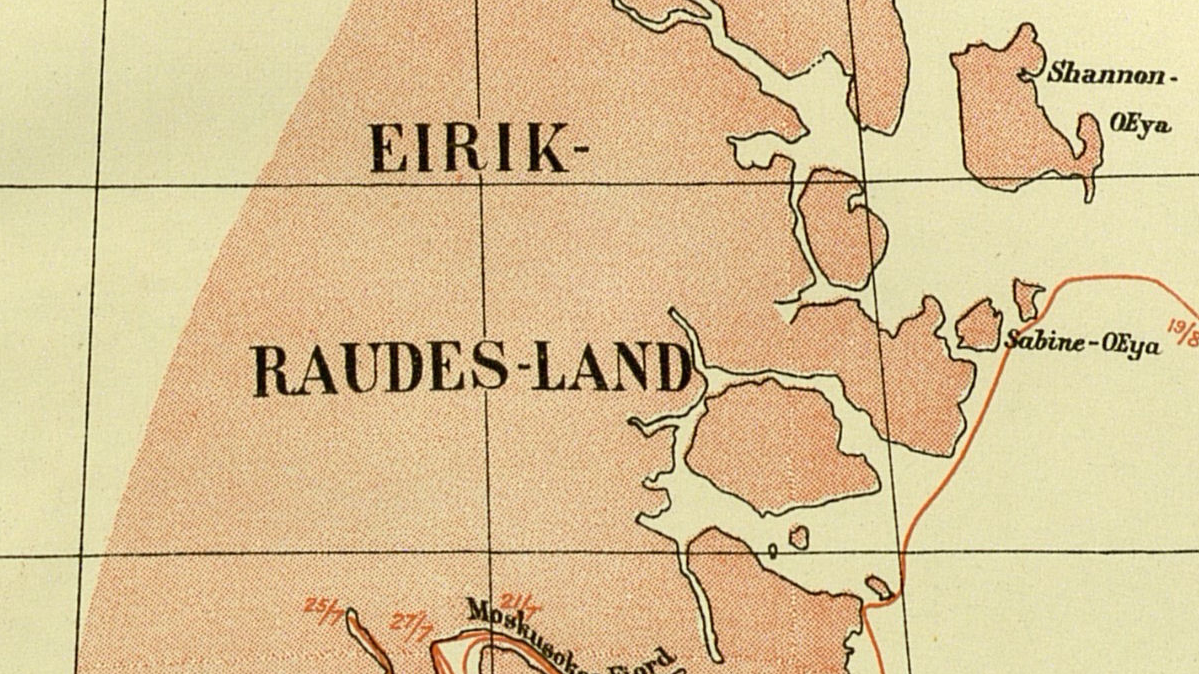

In 1931, Norway annexed part of Greenland. It could have been the start of a very Cold War indeed.

Civil rights leader Mary McLeod Bethune on never giving in to discrimination:

“If we accept and acquiesce in the face of discrimination, we accept the responsibility ourselves and allow those responsible to salve their conscience by believing that they have our acceptance and concurrence. We should, therefore, protest openly everything… that smacks of discrimination or slander.”

Do you dig social media, kung fu, ascetic lifestyles, and the color orange? If so, the Shaolin Temple has just the job for you.

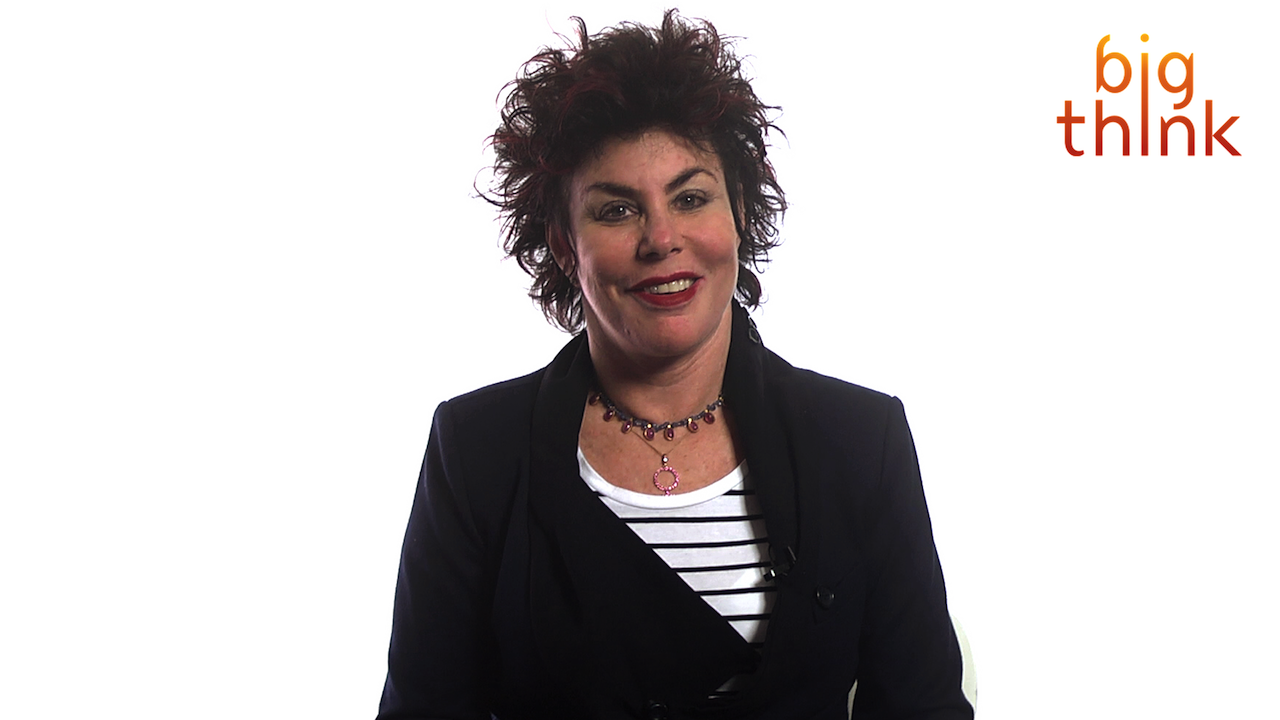

During a recent bout with depression, comedian Ruby Wax took time off from her career to pursue a Master’s degree in Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy from Oxford University.

The cosmic background radiation of the Universe once fried everything, but is now barely above absolute zero. Where did that energy go? “I think one of the coolest things you […]

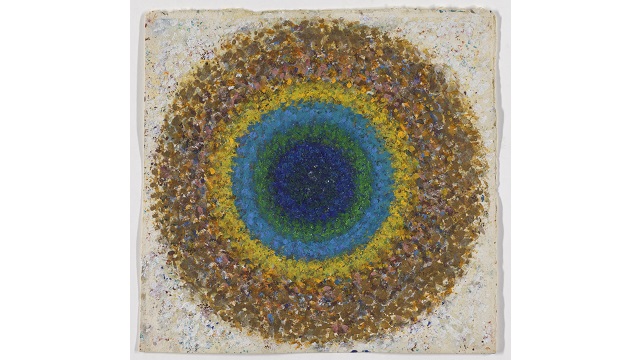

“The extasy [sic] of abstract beauty,” artist Richard Pousette-Dart scrawled in 1981 in a notebook on a page across from a Georges Braque-looking abstract pencil drawing. Although included in Nina Leen’s iconic 1951 Life magazine photo “The Irascibles” that featured Abstract Expressionist heavyweights Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman, Pousette-Dart has always stood on the edges, as he does in the photo, of full identification with that group.

This International Women’s Day, celebrate Henrietta Leavitt, who took us beyond the stars and into the galaxies. “Her will tells nearly all. She left an estate worth $314.91, mostly in […]

According to a story doing the rounds on social media, organ transplant patients can take on the personalities of their donors. Don’t believe the hype.

How we’re still, only now, just discovering the closest stars to Earth. “As a boy I believed I could make myself invisible. I’m not sure that I ever could, but […]

Lessons from the Universe whenever a light goes out. “End? No, the journey doesn’t end here. Death is just another path, one that we all must take. The grey rain-curtain […]

The United State owns the market on personal data with companies like Facebook and Google. This puts America in a position of power when talking about privacy rights. But that may mean being at odds with the international community.

How a funny idea to ship your enemies glitter turned into an empire. “There is a concept that is the corrupter and destroyer of all others. I speak not of […]

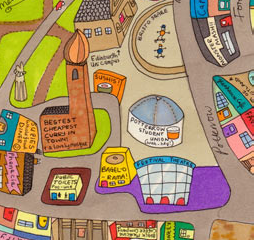

Edinburgh is the “grey metropolis in the North.” It has been for centuries, and thanks to Unesco, the capital of Scotland will keep its dour exterior for the foreseeable future. […]

Ever since American Commodore Matthew C. Perry sailed into Uraga Harbor near Edo (the earlier name for Tokyo) on July 8, 1853, ending the isolationist policy of sakoku and “opening” (willingly or not) Japan to the West, “the Land of the Rising Sun” and its culture have fascinated Westerners. Yet, despite this fascination, true understanding of that history remains elusive. A new exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Ink and Gold: Art of the Kano builds a cultural bridge for Westerners to Japan’s heritage through the art of the “Kano School,” a family of painters to the powerful who influenced all of Japanese art from the 15th to the late 19th century. Combining the sumptuousness of golden artworks with the compelling story of their makers, Ink and Gold: Art of the Kano offers the key to unlocking the mystery of Japan through the art of the Kano.

The Universe contains black holes billions of times as massive as our Sun. “It is by going down into the abyss that we recover the treasures of life. Where you […]

The Great Orion Nebula is so great, it needed a second Messier object all to itself! “Be not afraid of greatness. Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and others […]

Wearable technology is the future, but questions still persist as to where on the body the most popular devices will be worn. According to some prognosticators, temporary tech tattoos will reign supreme.

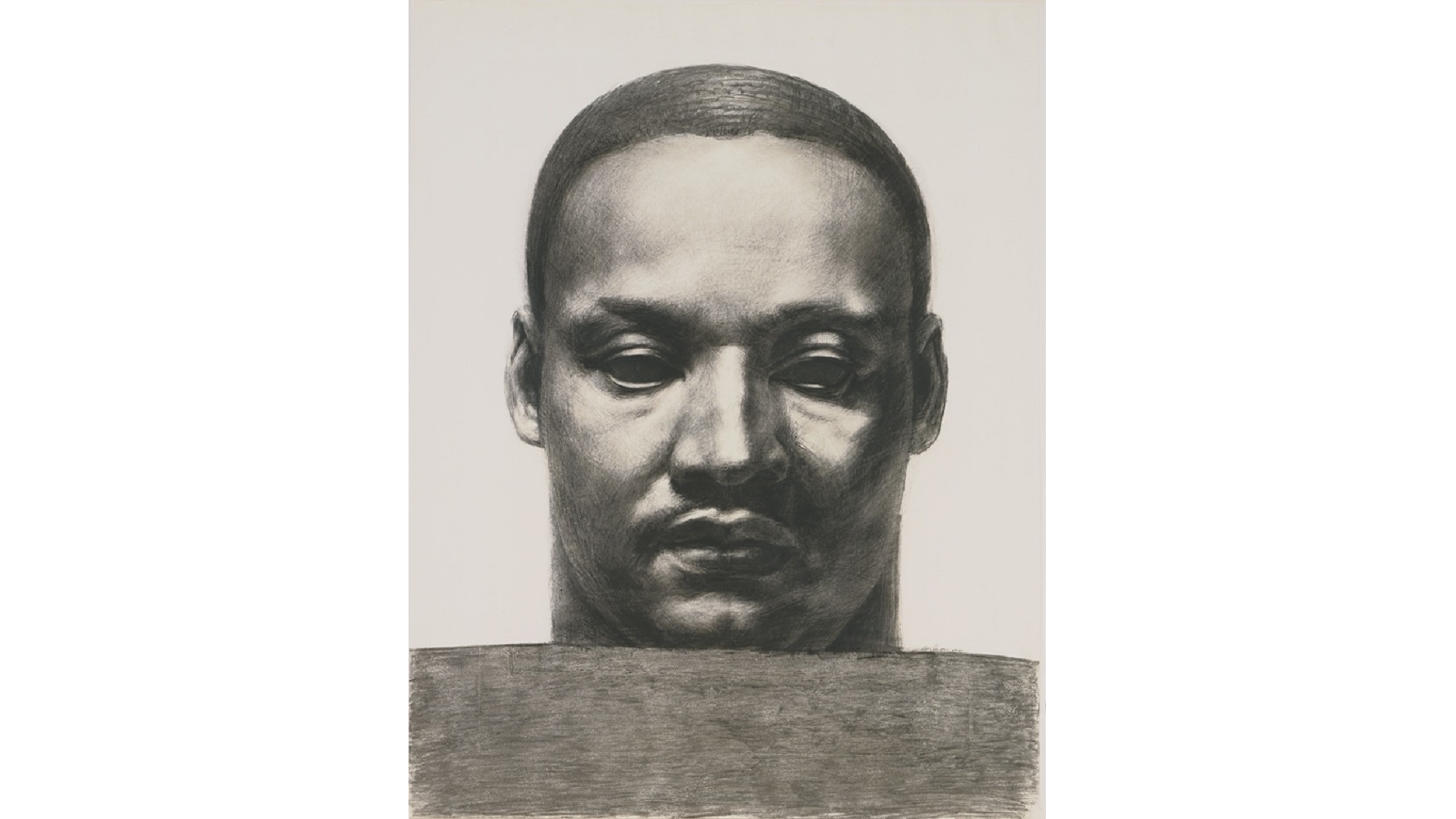

When the Philadelphia Museum of Art purchased Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting The Annunciation in 1899, they became the first American museum to acquire a work by an African-American artist. That purchase announced a new era of recognition of African-American art and artists just as much as the painting itself announced a new style of art moving away from stereotypical “black” scenes towards a freedom of aesthetic choice. Persons of color could express themselves in any way, even abstraction, but faced the new problem of remaining true to themselves at the same time. The new exhibition Represent: 200 Years of African American Art and accompanying catalogue show how these artists faced the challenges posed to them by art and society and provide all of us with a fascinating guide to facing African-American history—tragic, tenacious, transcendent—through its art.

How the location of the famous Ebbets Field facade appears today in Brooklyn, NY. (h/t @DugoutLegends)