Mapped: The strange link between obesity and corruption

- Corruption makes you fat — that’s the hypothesis behind a creative study that compared body mass index (BMI) with conventional measures of corruption in post-Soviet countries.

- The study found that the BMI of government ministers is highly correlated with the corruption of those governments.

- The study earned an Ig Nobel prize, but questions remain: What if you’re corrupt and health-conscious?

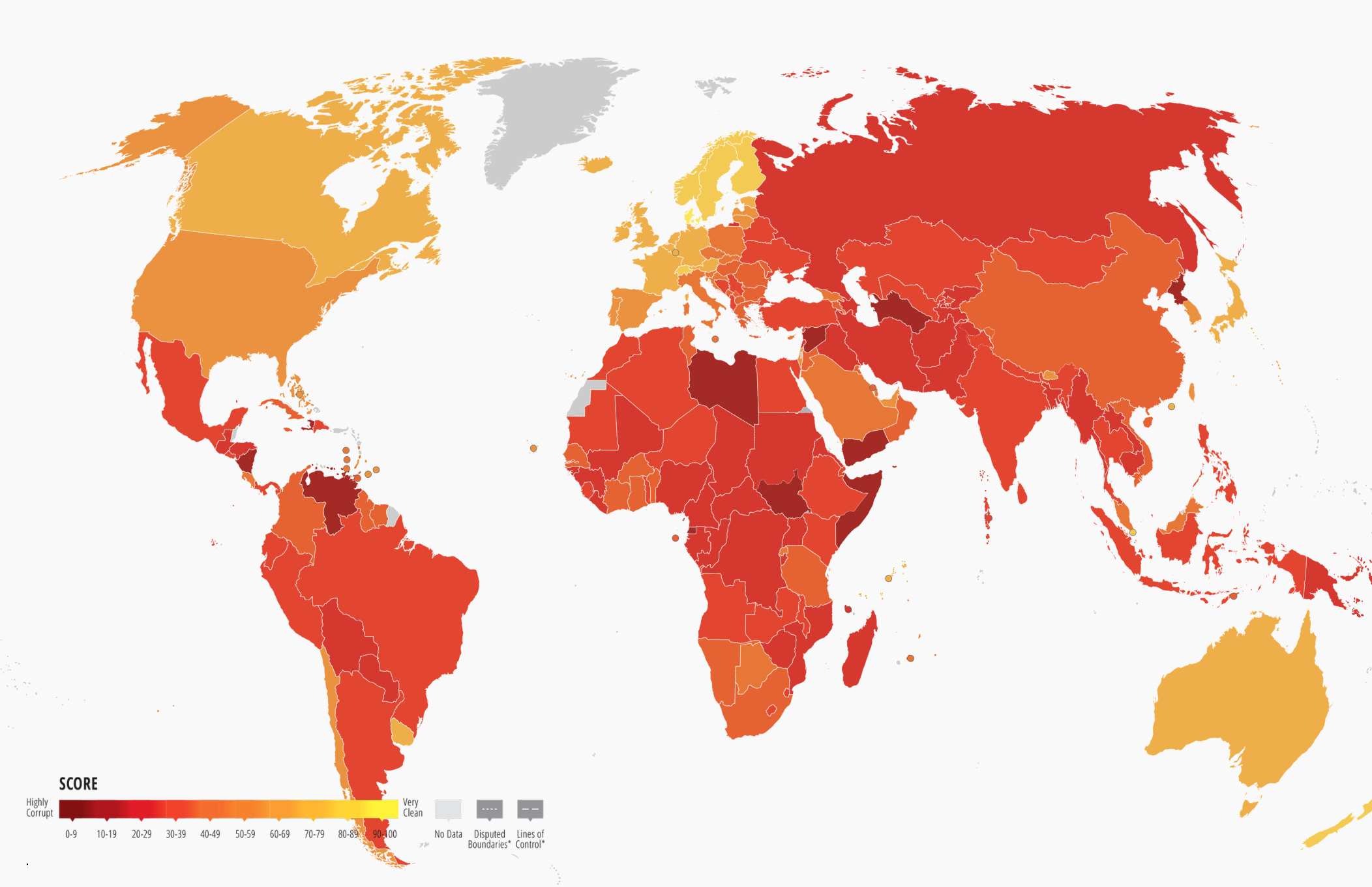

Country-level corruption is a tough KPI to quantify. So how do organizations like Transparency International and the World Bank do it? Not by comparing the fiscal, economic, and financial data of each country — they’d only end up comparing (rotten) apples to (spoiled) oranges.

Instead, to arrive at their Corruption Perceptions Index and Control of Corruption Indicator (respectively), they aggregate the opinions of experts in governance and corruption.

In 2020, Pavlo R. Blavatskyy, a professor of economics at Montpelier Business School in France, suggested a yardstick for country-level corruption that’s possibly more straightforward, but certainly more unexpected and more fun: the median body mass index (BMI) of a country’s government ministers.

Blavatskyy postulated that there is a positive relationship between the median BMI and a country’s level of government corruption. In plain English: If your country’s top officials tend toward obesity, your country is more corrupt, and vice versa.

The basis for this rather creative methodology is what Blavatskyy calls the “hedonistic theory of corruption.” Lavish banquets with lots of good food and drink are one of the most common forms of corruption, the theory goes, so the assumption is that these binges have a cumulative, measurable effect on the body weight of government ministers.

To test that theory, Blavatskyy’s team collected the frontal face images of government ministers of the 15 post-Soviet states in function in 2017 and used an algorithm to estimate the BMI of those 299 officials.

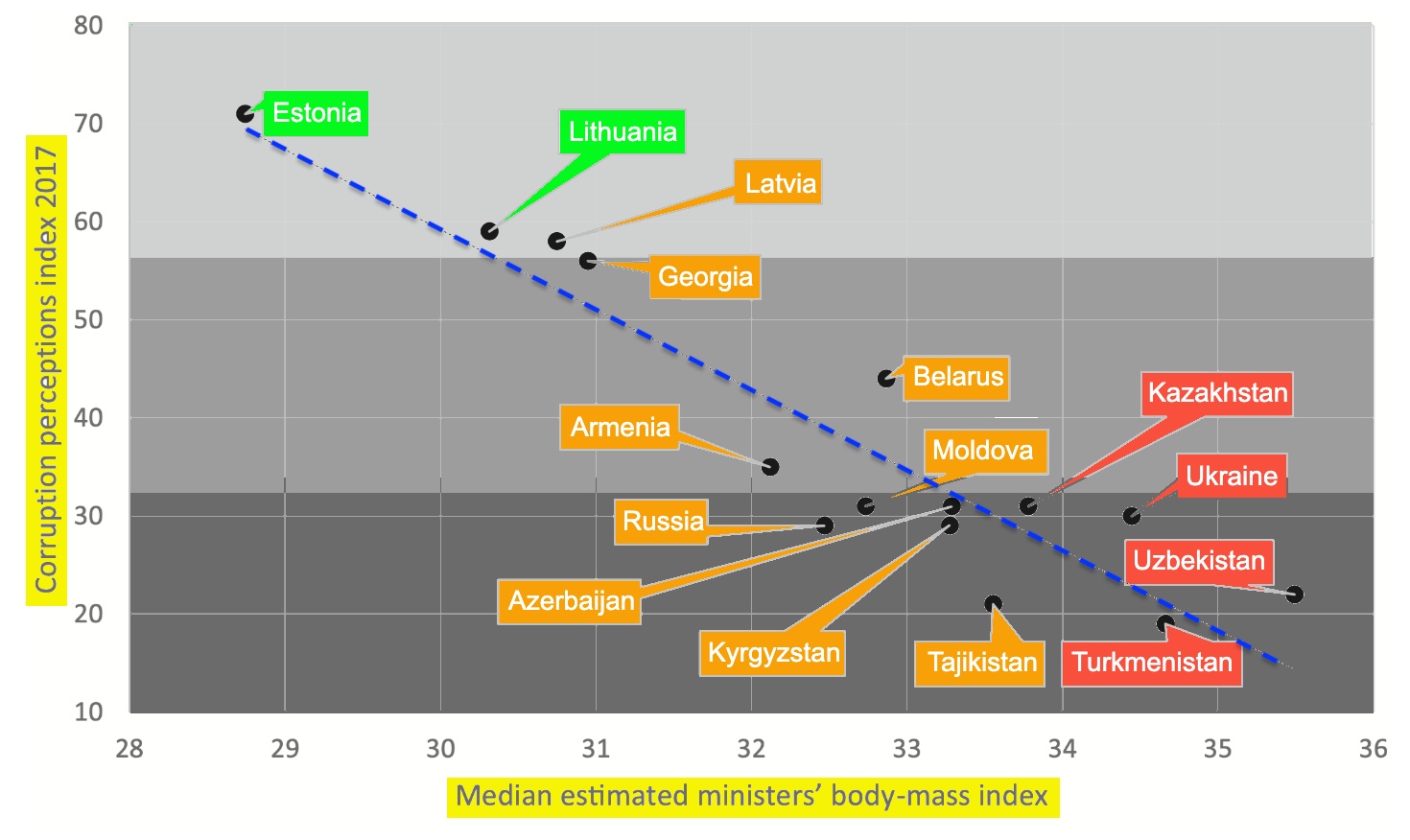

As shown by the graph, the median BMI of those cabinet ministers (horizontal axis) did indeed correlate strongly with one of the more conventional measures of national corruption levels mentioned earlier (vertical axis).

On a scale from 28 to 36, the horizontal axis shows the median BMI for each of the governments of those 15 post-Soviet countries in 2017. BMIs in the lower third are labeled green; in the middle third, they’re orange; and in the highest third, they’re red. Simply put: skinnier politicians to the left, heavier ones to the right.

The vertical axis shows Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index for 2017, with countries in the top third (light grey) least corrupt, and those in the bottom third (dark gray) most corrupt.

- The two countries with the lowest median BMI also score best on the Corruption Perceptions Index: Estonia has the least obese ministers and the least corruptible ones, with Lithuania in second place for both metrics.

- By a whisker, Latvia finds itself in the middle third of the BMI scale, but the country is still in the least serious third of the corruption index — if only just. Georgia is right on the edge of the middle third.

- Armenia and Belarus are in the middle category for median BMI and corruptibility.

- Moldova, Russia, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan are all in the middle third for BMI, but in the most serious third for corruption.

- The four most corrupt post-Soviet countries are also the ones where government ministers have the highest median BMI: Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. The bottom categories don’t entirely line up: Uzbekistan’s ministers have the highest median BMI, but Turkmenistan has the worst score on the corruption perceptions index.

“This result suggests that physical characteristics can be used as proxy variables for political corruption when the latter are not available, for instance at a very local level,” Blavatskyy says.

Professor Blavatskyy’s study on BMI and corruption won him the Economics prize at the 2021 Ig Nobel Awards, the annual celebration of quirky research.

Still, there are some problems with the findings. Besides the fact that this correlation doesn’t prove that corruption causes higher BMI, or vice versa, the findings are based on data from 2017. A lot has changed in the region since then, most notably the war in Ukraine, which has shaken up the governance standards of that country at least: Ukraine’s ratings in the Corruption Perception Index have improved from 30/100 in 2017 (130th out of 180 countries) to 36 in 2023 (104th out of 180).

Also, this method assumes that corruption automatically manifests itself measurably as debauchery of the food and beverage variety. This may be a tradition particular to (if not necessarily limited to) the former Soviet space. In other parts of the world, corruptible officials may put a higher value on their personal physical well-being and prefer cash, gold, or other valuables — perhaps even fancy gym memberships — as a means of recompense.

For the original paper, see Pavlo Blavatskyy, 2021. “Obesity of politicians and corruption in post‐Soviet countries,” Economics of Transition and Institutional Change, John Wiley & Sons, vol. 29(2), pages 343-356, April.

Strange Maps #1263

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Follow Strange Maps on X and Facebook.