Why is the Sun so active right now?

In case you thought the momentary absence of the Sun during April’s total eclipse was the biggest solar news of 2024, hold tight. This year is shaping up to be a wild one for our star.

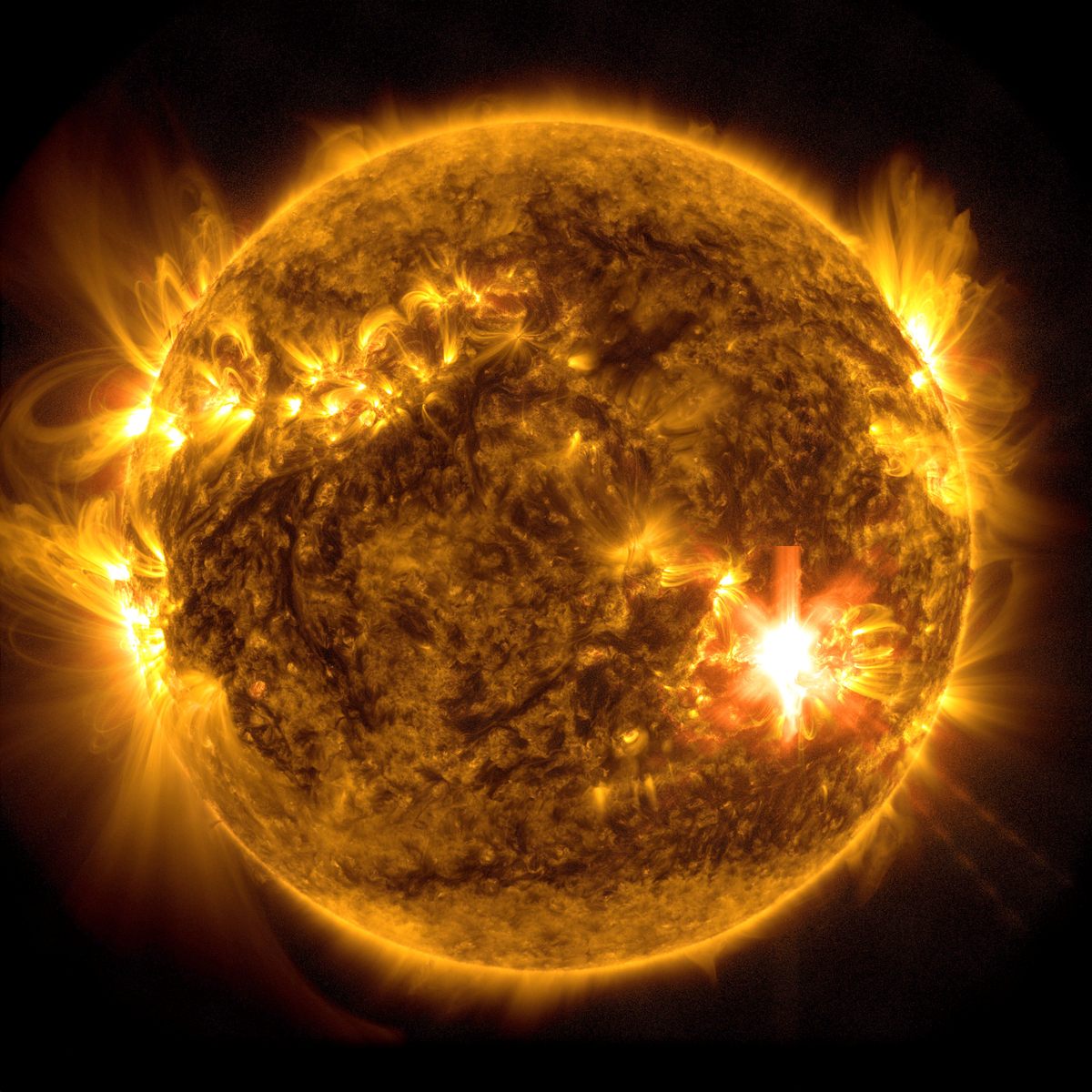

The Sun is behaving violently right now, throwing out fiery flares and spewing roiling clouds of plasma. Viewers across much of Earth were treated to an amazing show of the aurora in the last several days, with the northern lights visible as far south as Alabama and Arizona. The Sun’s behavior is something we should all watch this summer—and not just because solar action may continue to bring beautiful curtains of aurora to our night skies. The reliable, ferocious, and disorderly 11-year behavior cycle of the Sun is one of the most bizarre phenomena in our solar system.

First, a bit about what’s going on. The Sun has been active all of 2024, spewing out flares and coronal mass ejections, which are clouds of charged particles. Things got extra hectic when a huge and complicated cluster of sunspots unleashed several solar flares. The sunspot group is about 16 times wider than Earth, and the flares were all “X-class,” the strongest possible on the space weather scale—imagine a cluster of EF-5 tornadoes or Category 5 hurricanes, to use more familiar, earthly scales of violent weather.

Then, on May 9, space weather scientists saw five coronal mass ejections explode from the Sun and fly toward Earth. All of these clouds, which travel slower than light, arrived in Earth’s magnetic field over the weekend, sparking aurora around the world.

NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center issued a severe level 4 geomagnetic storm watch, its first since 2005. The concern is that CMEs can disrupt satellites, especially those at geosynchronous orbit, and interfere with radio communications and power grids on Earth. You don’t need to panic when these alerts are issued, but you should know that such disruptions will happen, if not during the current event then, inevitably, sometime in the future.

While solar activity can disrupt modern society, it is also one of modern astronomy’s most intriguing topics, in my view. The Sun is 4.6 billion years old, which is middle-aged for a star of its type, but nonetheless a span of time whose immensity is hard to comprehend.

My friend Peter Brannen has a helpful analogy for conceptualizing such deep time: Imagine a walk down the block where each step represents 100 years of history. After 20 steps, you stroll past Jesus. “After only a few dozen steps—before you can even reach the end of the block—all of recorded history peters out, all of human civilization is behind you, and woolly mammoths exist,” he writes in The Ends of the World. To get to the birth of the Sun, you would have to keep walking for 20 miles a day, every day, for four years. That’s how old the Sun is.

And yet, somehow, this unbelievably ancient thermonuclear furnace, the source of all life and possibility on Earth, acts out on a very human timescale. Its sunspot activity flares up and down every 11 years, the so-called solar activity cycle. Think about that for a moment: The 4.6 billion-year-old Sun switches between angry and placid about every Earthly decade. Not, for instance, some other random number like 87,000 years, or 11 million years, but, for reasons no one knows, the length of human childhood. The span of a dog’s life. Just short of three presidential elections. Why? Nobody knows. We likely never will.

In February 1755, scientists started measuring the recurrence of sunspots as a way to track the sun’s activity. This is now called Solar Cycle 1, and it lasted until June 1756. These blemishes on the face of our star are driven by magnetic activity, like most other solar phenomena.

We’re entering the “maximum” phase of Solar Cycle 25, when the Sun is most active and churning out the most sunspots and associated flares. And so far it’s a doozy. If you saved your eclipse glasses, go out and look at it—you can’t miss the big sunspot cluster on the Sun right now.

If you don’t have solar viewing glasses, I recommend looking through the Solar Dynamics Observatory, a gallery of live pictures of our star from a NASA spacecraft orbiting Earth. It views the Sun in many different wavelengths of light, rendering the star as a placid pink ball, a Moon-like disc of gray, or a turquoise sphere surrounded by angry flames, among other options. I am personally partial to the filter that combines several wavelengths of light into a view that looks like a purple-teal ball of fire.

Solar flares and coronal mass ejections fling radiation and charged particles into the entire solar system. They travel with the solar wind, and reach far beyond Pluto. This material was the last thing the Voyager 2 probe felt before it left the Sun’s influence for good. Coronal mass ejections in particular can harm satellites and astronauts in space and on the Moon, so they are worth our consideration and study.

But I like to think of solar activity, and its attendant aurora, as a reminder. Our star, a literal star in a vast and uncaring cosmos, is very much a part of us. It is eternal, in the most credible sense of that word, yet it acts on timescales that we can experience and perceive. We do not understand why this is, just as we do not fully understand how the Sun works. But we can look up and wonder, all the same.

Wondersky columnist Rebecca Boyle is the author of Our Moon: How Earth’s Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are (January 2024, Random House).

This article originally appeared on Atlas Obscura, the definitive guide to the world’s hidden wonder. Sign up for Atlas Obscura’s newsletter.