Hand-sanitizer resistant bacteria strains are developing

One of the few things that we can be sure of is that every action is likely to have an unintended consequence. While on a daily basis these side-effects can be annoying at worst or convenient at best, at institutional scales they can be dire. In some cases, they can be deadly.

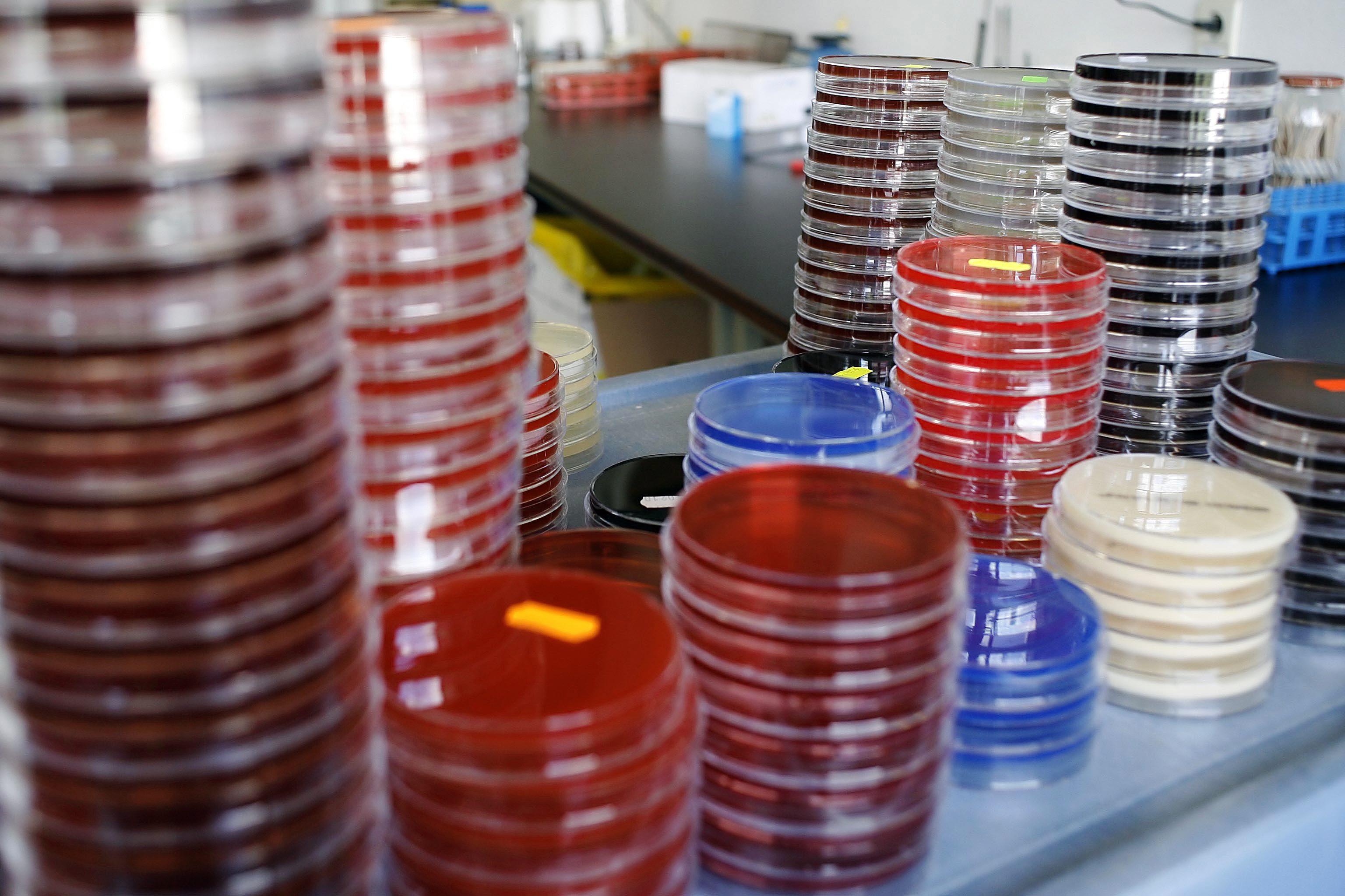

A new study published in Science Translational Medicine on the effects of hygiene practices in Australian hospitals gives us an excellent example of this, showing us how a wonderful program can have disastrous side effects.

What was the program? How did it foul up?

In 2002, Australian hospitals introduced new procedures to help cut down on MRSA infections which included hand washing with alcohol-based hand sanitizers before and after interactions with patients.

The hand sanitizer had the intended effect—new MRSA infections have been dropping for 15 years—however, study co-author Paul Johnson noticed that the decline in MRSA infections had been accompanied by a slow rise in Enterococcus faecium infections. He suggested that perhaps the bacteria were evolving tolerance to the alcohol-based sanitizers.

While the idea seemed far-fetched, an experiment was devised to confirm or deny the hypothesis.

What did the experiment show?

139 cultures of Enterococcal bacteria, a microbe that usually lives in our guts but can cause dangerous infections and even sepsis if it gets anywhere else, taken from Australian hospitals at different points over the last several years were treated with an alcohol solution similar to that used in common hand sanitizers.

As hypothesized, the newer strains showed more tolerance to the solution than the older ones did, demonstrating that the strain has evolved a higher tolerance to being smothered with alcohol over time.

The alcohol-tolerant bacteria were also found to be capable of living in the guts of mice living in an environment that was cleaned with alcohol, showing that the tolerance wasn’t a fluke limited to a petri dish.

Somehow, this isn’t even the scariest experiment involving mice we know about. (SAM YEH/AFP/Getty Images)

Wait, what?Is this even possible?

That was the exact reaction of co-author Tim Stinear. Ethyl alcohol kills germs in a very gruesome fashion, literally dissolving the lipids that hold the cell together while simultaneously preventing vital cellular functions from occurring. It would be like a person going into a vat of battery acid.

Bacteria that can tolerate this for extended lengths of time before dying boggle the mind.

Reflecting on the idea that inspired the study, professor Stinear recalled, “Paul (Johnson) said ‘maybe they’re becoming tolerant to all the alcohols we use in our hand hygiene products’ and we said, ‘that’s ridiculous. What are the chances that something could become tolerant to alcohol?’”

You know something’s wrong when a doctor thought that what’s happening was too absurd to consider.

How did it happen?

The effectiveness of hand sanitizers is dependent on proper usage. The WHO recommends that people rub sanitizer on their hands for 20-30 seconds, but of course, not everybody does that. Using any antimicrobial agent at a subtherapeutic level can lead to bacterial immunity and is a leading cause of antibiotic resistance.

Essentially, bacteria that weren’t killed by the alcohol rubs, either because they were exposed for just too little time or they had a natural mutation that gave them some protection, were able to survive and multiply while those that were killed off did not. Natural selection took its course.

How bad is this?

Extremely bad, if the current trend continues.

Some strains of Enterococcus faecium are already resistant to last-line antibiotics, meaning that they are challenging to treat when an infection occurs. If they were to become more tolerant than they are to the hand sanitizers used in hospitals, then we could easily see a scenario where entire hospital wards are shut down to try to contain outbreaks of a disease that can neither be readily treated or prevented. Such things have happened before over MRSA infections.

The hospital environment—filled with people who are already ill and extra vulnerable to such a disease—would inflate the death toll from such an outbreak.

Is there any good news?

Yes, there is.

Firstly, the bacteria still die when placed in higher concentrations of alcohol. However, this is stronger than many hand sanitizers used at hospitals. It does suggest that we aren’t quite doomed yet.

Secondly, this tolerance to alcoholic sanitizers doesn’t extend to other hygiene practices. Handwashing, which doesn’t kill bacteria so much as it lifts them off your hands and flushes them down the drain, is still effective against pretty much everything, but don’t be taken in by the notion that antibiotic soaps are of much use.

The measures introduced in Australia to reduce MRSA infections in hospitals were largely successful but had the side effect of increasing the number of Enterococcus faecium infections. If left unchecked, this new problem could prove deadlier than the last one.

While we don’t have to worry about an apocalyptic pandemic just yet, this story should remind us that we can’t fully control our environments and that even well-enacted plans with the best of intentions can have horrible results on the side.